Caption

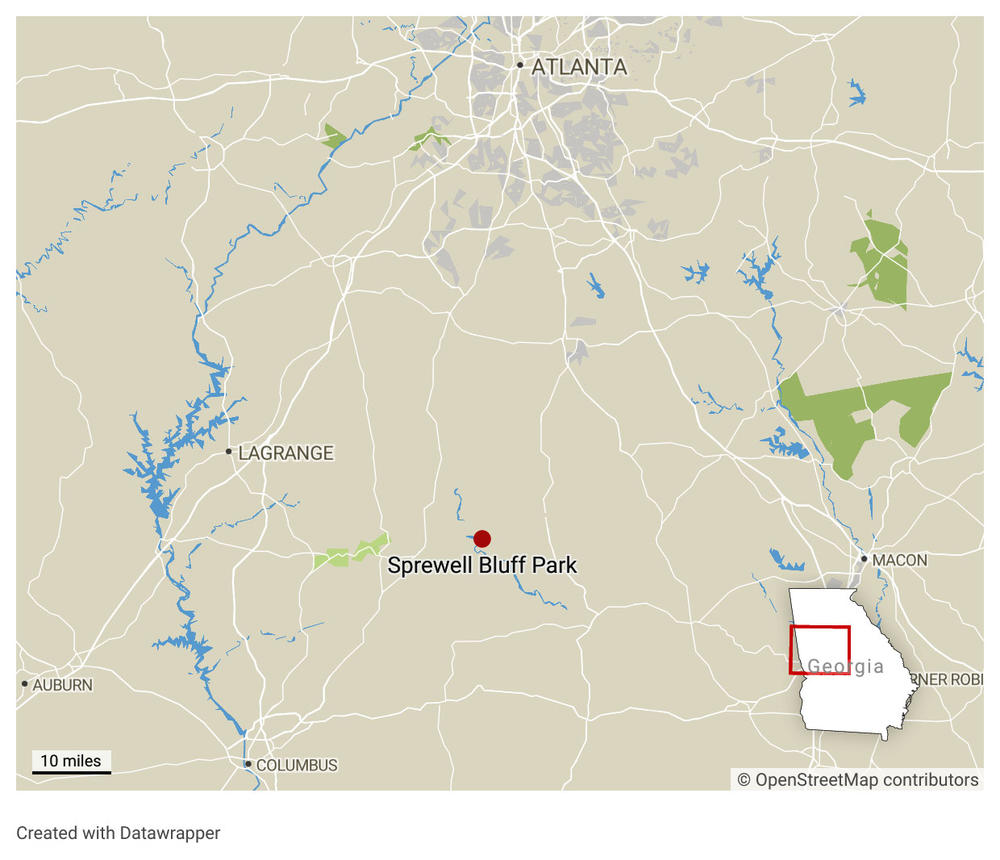

Sprewell Bluff Park is located in Upson County, between the Atlanta metro area to the north, Macon to its east and Columbus to its southwest.

|Updated: December 31, 2024 2:51 PM

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story was originally published March 2023, after former President Jimmy Carter entered hospice care. Carter died Dec. 29 in Plains, Ga.

——

Think of all of Jimmy Carter’s plaudits.

“Builder of homes for the poor.”

“Eradicator of disease.”

“Champion of world peace.”

“Teacher of his faith.”

Now add “Protector of rivers.”

About halfway between Macon and Columbus, a little west of Thomaston, is a place called Sprewell Bluff.

You get there by driving a winding road to a small beach. When you face the water, hiking trails lace the hill behind you.

Sprewell Bluff Park is located in Upson County, between the Atlanta metro area to the north, Macon to its east and Columbus to its southwest.

In front of you, past shoals and a boulder from which people leap into the river during summertime, is Sprewell Bluff itself, jutting 500 feet above the water.

West from there you’ll find rare, old-growth longleaf pine forest. A little further north, the pine forest blends with plants you’d find in the Appalachian highlands, such as mountain laurel.

Experts will tell you the abundance of plant and animal species resulting from the collision of the Coastal Plain, the Piedmont and the Appalachian Chain in the area near Sprewell Bluff makes it nearly one of a kind — not just in Georgia but in the world.

And so even on slow days, Sprewell Bluff Park coordinator Sarah Williams works in the park store back up the hill from the beach.

Williams loves this place as much as visitors, although she says they aren’t always sure about what they are seeing.

“You know, we have people even call this 'the lake' down here,” she said, as the wind drew clinking noises from the flagpole across from the store.

“We're like, ‘No, it's a river, you know?'”

Namely, the Flint River.

But Sprewell Bluff — and all surrounding it — came very close to being the bottom end of a lake, if not for Jimmy Carter.

Janet Morgan Mapel remembers being excited about the idea of a new lake when she was a child.

Janet Morgan Mapel remembers being intrigued by the idea of water skiing out the back door when the Sprewell Bluff Dam was discussed in the 1970s. She also remembers her father fighting tooth and nail to keep it from happening.

“I'm thinking water skiing; I think I had just learned to water ski,” she recalled on a chilly morning on the public boat ramp across the Flint from the home where she once lived. “I wasn't a part of Dad's business, a part of the agriculture or whatever, but I was a part of hearing him so concerned.”

Tom Morgan was Mapel’s dad. In the 1970s, when Mapel was in eighth grade, her dad was a farmer who ran a fertilizer business in the town of Woodbury. Mapel said her dad was concerned because he loved, maybe even lived for, the trips down the Flint River that started right out their back door.

“We would just slide the canoe down,” she said.

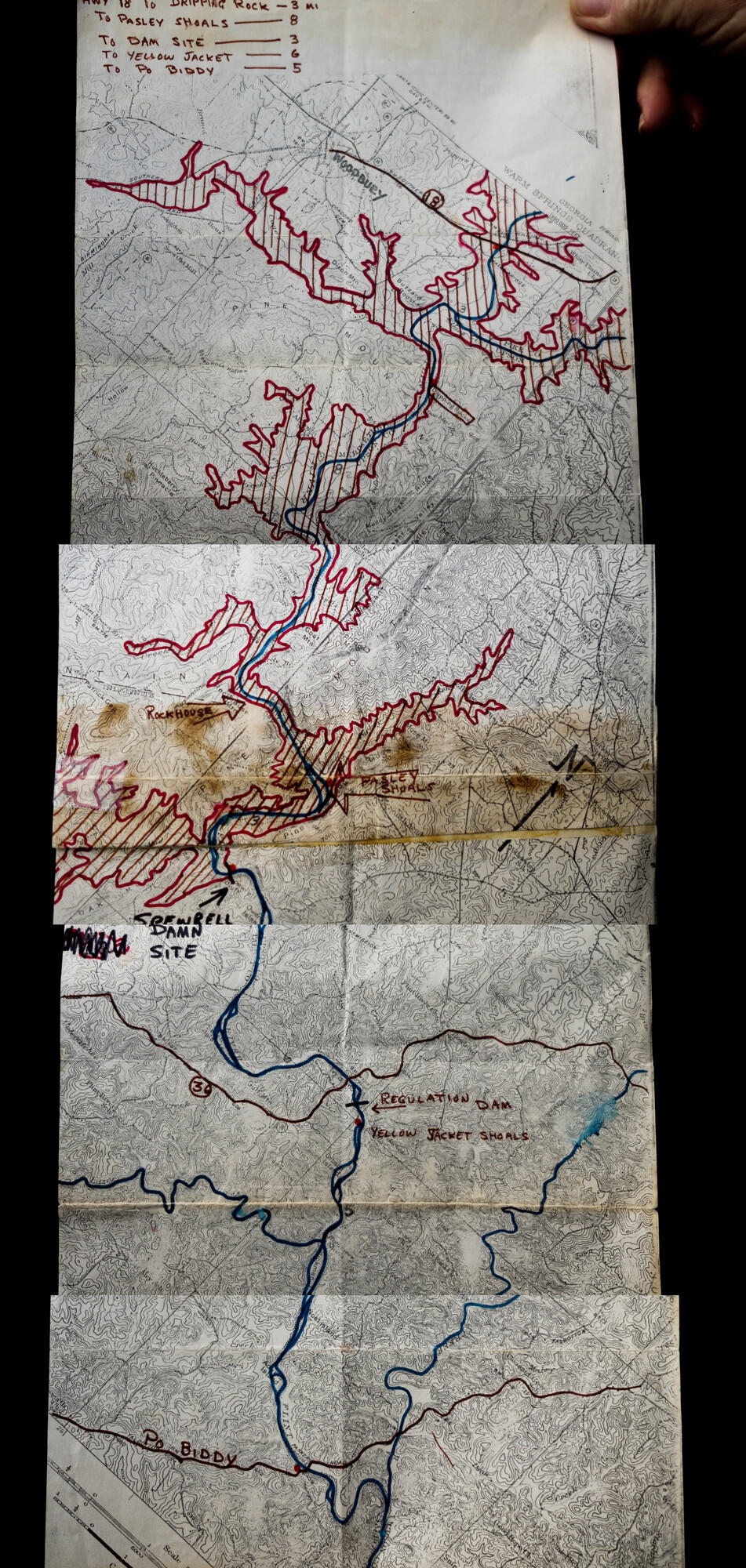

And like otters down the river bank, they’d cut through the crumpled ridges of Pine Mountain, through places with names like Dripping Rock and Pasley Shoals. Mapel has a ready list of the precious things there.

An approximately 50-year-old map of the planned Sprewell Bluff Dam project on the Flint River made by Tom Morgan and now owned by his daughter Susan Mapel.

“You've got the spider lilies down the way," she said. "You've got mussels; you've got the river shoal bass."

The Cahaba lily is only found in the shoals of fall line rivers around the South. Most of those rivers were dammed. The shoal bass is now the state fish of Georgia.

Then, up on the bluff, there are endangered red cockaded woodpeckers and bachman’s sparrows. There are coral snakes. Their homes are maintained by intentional, prescribed fires today.

But back in the ‘70s, politically powerful entities, including the ironically named U.S. House member John James Walker Flynt Jr., wanted the dam.

Tom Morgan would tell anyone who would listen to oppose the project of the Army Corps of Engineers that would have drowned the lilies, the shoals and would have left a lake lapping at his door.

“You know, if he was going to give a speech, he would practice at home and I would hear him,” Mapel said.

The allies Morgan won often shared traditions of farming and outdoor life. Luckily for them, one of their own was in the governor’s mansion.

“A lot of other outdoor people were involved in even getting Jimmy Carter to get on the river and go down it,” she said. “And just to see: 'Before you make any decision, see what you are going to be destroying.'”

That’s what Gov. Jimmy Carter did.

“I personally canoed down the river twice,” Carter writes, in the preface to a 2001 book by Fred Brown and Sherri Smith called A Recreational Guide to the Flint River.

Carter was taken by the beauty he saw.

“The wildlife that exists in that river corridor,” he wrote, “Otter, fox, muskrat, beaver,bobcat... You cannot describe it.’

On the other hand, Carter was a businessman who had a responsibility to consider the economic impact a new lake might make.

Martin Doyle is a professor of environmental science and public policy at Duke University. He said that’s where another, more fundamental side of Carter came into play.

"Carter was an engineer,” Doyle said. "I think he was a nuclear engineer from Annapolis."

Doyle's recollection was accurate: Carter was a nuclear engineer in the U.S. Navy. And so Carter the engineer applied scientific rigor to the question of the Sprewell Bluff Dam.

“And so the way that he seems to make sense of it is, is 'I got to go and look at these numbers myself,'” Doyle said.

By numbers, Doyle meant the cash benefits the Army Corps of Engineers said would flow into communities around Sprewell Bluff after the dam was done.

“And Carter kind of dug into them and he said, ‘Well, No. 1, I think that they're overestimating the benefits,'” Doyle said.

In his preface to the guide book to the Flint, Carter was far more blunt: He called the Corps of Engineers' economic projections “a complete passel of lies.”

Convinced the dam would be useless, then-Gov. Carter vetoed the project. Later, as president, Carter remained convinced he’d found a pattern of overpromising around federal dam projects. He would veto projects across the country.

“And that that pivot in particular sets the dam building industry back on its heels,” Doyle said.

Some dams got built anyway, most notably the Tellico Dam in Tennessee which Carter ended up signing off on against his better instincts after he was outmaneuvered by Congress.

But before he left office, Doyle said Carter installed into the machinery of federal funding a piece of his thinking about how dams should be built.

It had to do with who was paying.

“If the federal government was paying for 100% of the cost, there's no reason for a congressional representative or a senator or the local community to not want a project,” Doyle said.

Or, as Carter wrote, “One of a congressman's goals in life was to have built in his district a notable dam at federal government expense that created a lake that could be named for him.”

For Carter, this was the very definition of pork barrel politics, and while government make-work may have lifted the South and the nation out of the Great Depression 40 years prior, the president felt that by the 1970s its time was done.

“And what Carter started was what was called a local sponsorship that the local benefiting community had to put up about 25% of the costs of a dam,” Doyle said. “But dams are really expensive. And so if the local community or the state had to come up with 25% of a really big-ticket item, all of a sudden the local community started to look at the numbers a little bit more carefully and ask, 'Are we actually going to benefit from this?'”

And how much do we really want to water ski?

“Exactly right,” Doyle said. “And do you value it that much?”

Doyle said the fiscally conservative step by Carter was really a presage of what was to come from the White House.

“He was Reagan before Reagan was Reagan,” Doyle concluded.

Under President Ronald Reagan, the mandated local buy-in for a federal dam would ramp up to 50% of the price tag. Doyle said that, plus a growing dearth of easy places to dam, meant half as many new projects in the decade after Carter left Washington.

Jimmy Carter apparently never quit caring for the Flint River.

As recently as 2008, Georgia politicians again floated the idea of a Sprewell Bluff dam, this time to satisfy a thirsty Atlanta. Carter, by then six years a Nobel peace laureate, spoke for the river again and the idea faded away.

“Lakes and dams are everywhere,” Carter said in the preface to that 2001 guidebook. “But to experience something that is undisturbed and has its natural beauty?

“You hope and pray that it will be there a thousand years in the future, still just as beautiful and undisturbed."

An earlier version of this story misspelled the name of Flint River landmark Pasley Shoals.