Section Branding

Header Content

Scientists think they know why interstellar object 'Oumuamua moved so strangely

Primary Content

Scientists have come up with a simple explanation for the strange movements of our solar system's first known visitor from another star.

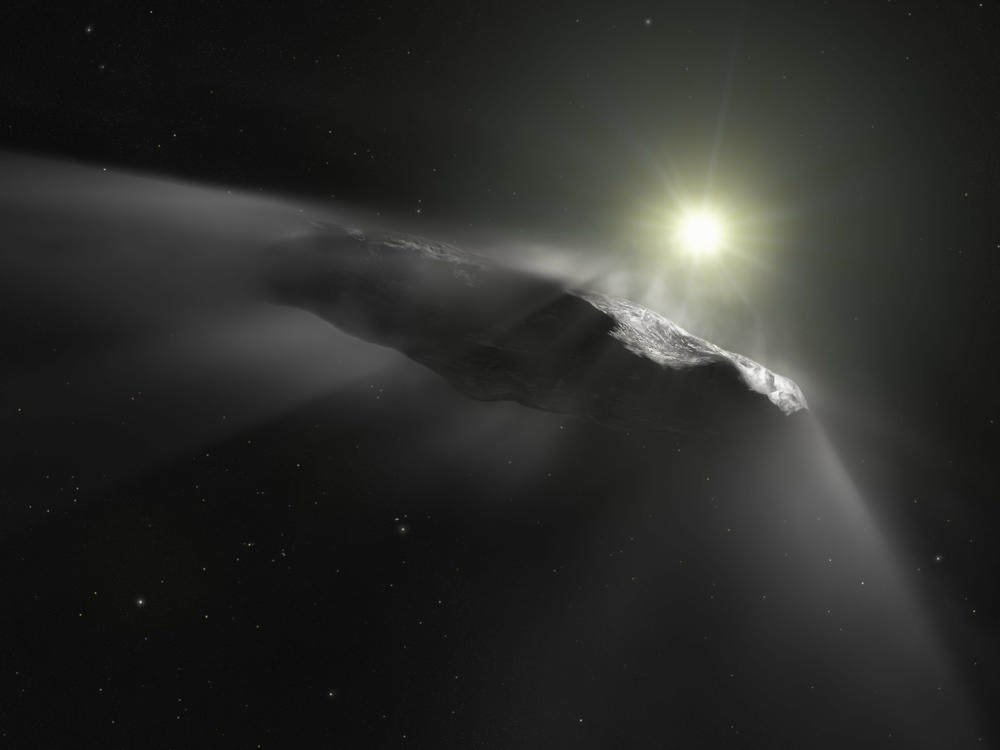

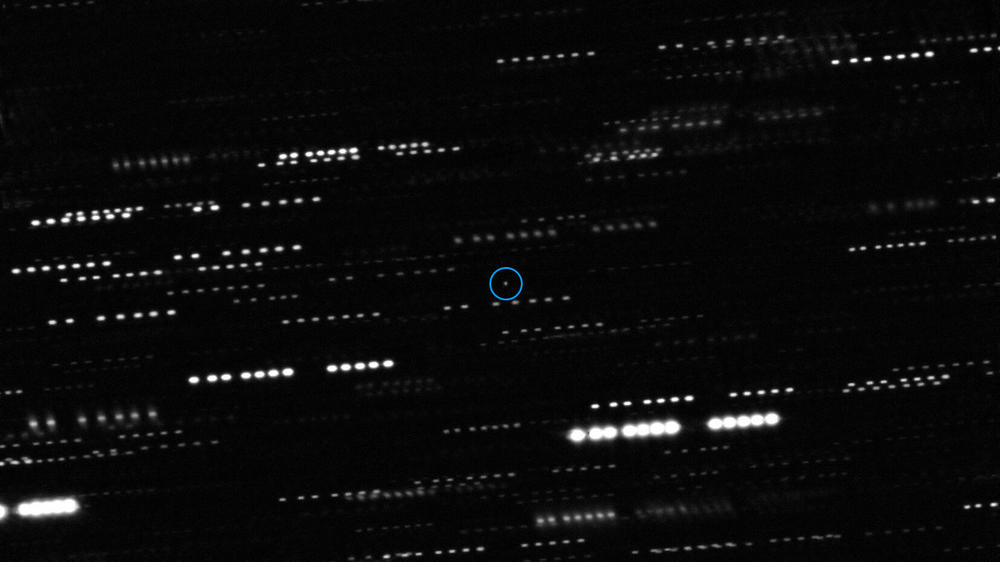

In October of 2017, astronomers in Hawaii spotted an object they called 'Oumuamua, which means "a messenger from afar arriving first," according to NASA. The reddish object was shaped like a cigar or a pancake, and was over 300 feet long. Its trajectory indicated that it had come from another solar system, traveling through the Milky Way galaxy for hundreds of millions of years before encountering our sun.

Oddly, this interstellar object appeared to be slightly accelerating in a way that normally is associated with the outgassing of some kind of material. But astronomers couldn't detect any comet-like tail of dust or gas.

Over the last few years, some speculated that the object must be made of exotic materials, and the mystery even led to suggestions that 'Oumuamua could be some kind of alien probe or spaceship.

Now, though, in the journal Nature, two researchers say the answer might be the release of hydrogen from trapped reserves inside water-rich ice.

That was the notion of Jennifer Bergner, an astrochemist with the University of California, Berkeley, who recalls that she initially didn't spend much time thinking about 'Oumuamua when it was first discovered.

"It's not that closely related to my field. So I was like, this is a really intriguing object, but sort of moved on with my life," she says.

Then she happened to attend a seminar that featured Cornell University's Darryl Seligman, who described the object's weirdness and what might account for it. One possibility he'd considered was that it was composed entirely of hydrogen ice. Others have suggested it might instead be composed of nitrogen ice.

"Hearing about some of the explanations that people had come up with to explain the strange properties with 'Oumuamua sort of piqued my interest," says Bergner.

Bergner wondered if it could just be a water-rich comet that got exposed to a lot of cosmic radiation. That radiation would release the hydrogen from the water. Then, if that hydrogen got trapped inside the ice, it could be released when the object approached the sun and began to warm up. Astronomers who observed 'Oumuamua weren't looking for that kind of hydrogen outgassing and, even if they had been, the amounts involved could have been undetectable from Earth.

She teamed up with Seligman to start investigating what happens when water ice gets hit with radiation. They also did calculations to see if the object was large enough to store enough trapped hydrogen to account for the observed acceleration. And they looked to see how the structure of water ice would react to getting warmed, to see if small shifts could allow trapped gas to escape.

It turns out, this actually could account for the observed acceleration, says Bergner, who notes that the kind of "amorphous" water ice found in space has a kind of "fluffy" structure that contains empty pockets where gas can collect.

As this water ice warms up, its structure begins to rearrange, she says, and "you lose your pockets for hiding hydrogen. You can form channels or cracks within the water ice as parts of it are sort of compacting."

As the pockets collapse and these cracks form, the trapped hydrogen would leak out into space, giving the object a push, she says.

"It's an interesting, creative idea," says Karen Meech, with the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii, who leads the team that initially found and observed 'Oumuamua. "It doesn't require a super-exotic mechanism."

But she still thinks it's possible that 'Oumuamua is just a regular, ordinary comet that released enough water, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide to account for the acceleration, and astronomers just didn't detect it.

"What a lot of people don't realize is that in order to get a good spectrum to detect the gas, you usually have to have a pretty bright comet," she says. "And 'Oumuamua was not bright."

And even though no one detected dust coming off of it, she says it's possible that it wasn't throwing off the kind of fine dust that instruments look for. That's why she thinks "it's not outside of the bounds of reality that you could get it to all fit with it as a regular comet."

Still, she's very pleased that so many different people have been drawn to trying to figure out this interstellar visitor, even though 'Oumuamua is now so far off that can't be observed anymore.

To her, the most compelling mystery about this object remains its shape. "It was so elongated," she says.

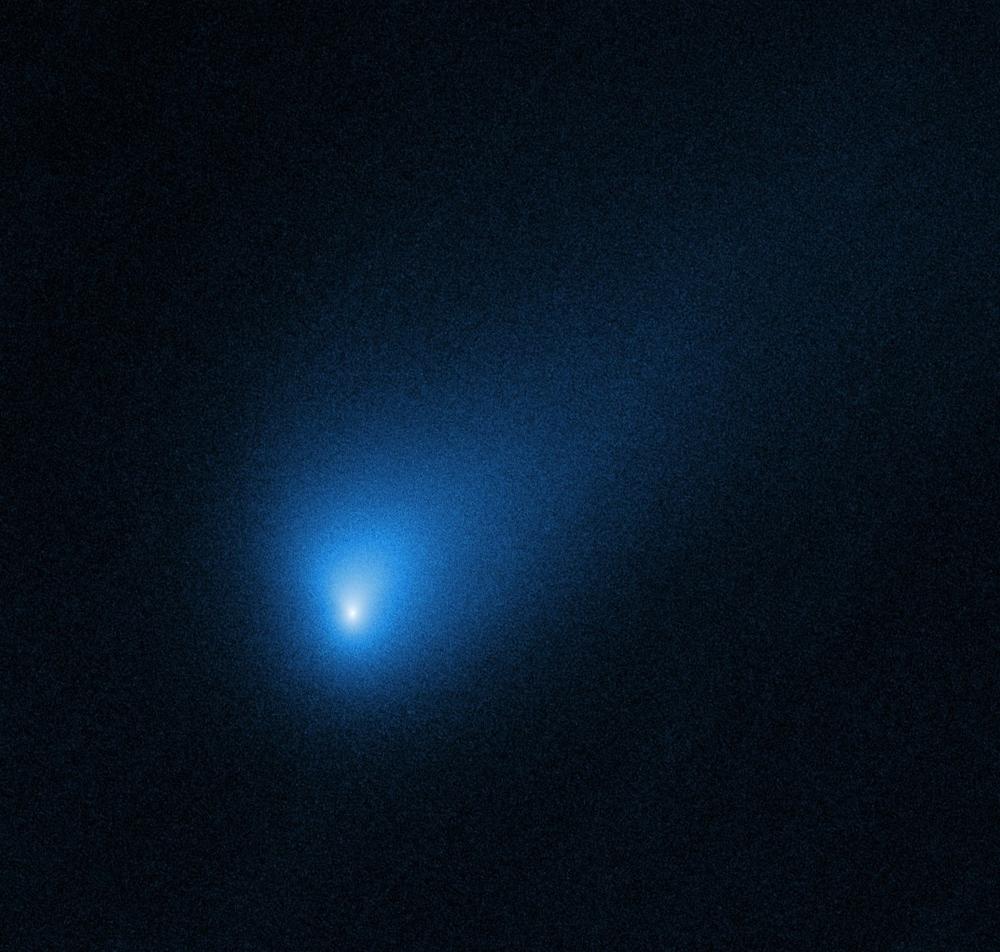

A second interstellar object was discovered in 2019, and Meech says it's thought that there's pretty much always at least one inside the orbit of Earth, closer to the sun.

"It's just that we don't see them," she explains. "They're either small, they're dark, or they're not in a position where you can point telescopes."

In 2024, the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory should come online and open up a floodgate. "They're predicting maybe one interstellar object a year," she says.

That's a big deal, given that the closest star system to our own is over four light years away, and, with current technology, it would take thousands of years to send a probe there.

Meech notes that some researchers have already designed missions to intercept one of these interstellar travelers, which could contain clues about the composition of the star systems that formed them.

"I think what's important about this is to get all these creative ideas out there," says Meech. "If we ever get to have a mission to one of these objects, we now have a wealth of testable ideas."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Correction

An earlier version of a photo caption in this story inadvertently cut off the end of the photo credit. The correct credit is ESA/Hubble, NASA, ESO, M. Kornmesser.