Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia’s hedge against climate change: the Okefenokee’s peat

Primary Content

Mary Landers, The Current

As Michael Lusk pilots a flat-bottomed Carolina Skiff into the open water of the Okefenokee’s Grand Prairie, he spots his quarry. Several meters wide and dotted with grasses and water lilies it’s a soggy brown mat of peat that’s floated up from the bottom of the swamp. Lusk dangles his legs over the front of the boat and pushes down with his feet, jiggling the mat.

At that, Rena Peck can resist no longer. The executive director of the Georgia River Network scooches off the front of the boat and stretches her long legs to meet the floating islet at her feet.

Will it hold her weight? Only one way to find out. She stands up. Water swallows her footsteps, but she doesn’t punch through. Cautioned by Lusk about pushing her luck, Peck takes a few steps then grabs his hand to get back on the firm deck of the boat.

“Oh my gosh, that was so cool,” Peck said.

The Okefenokee gets its name from formations like these that are part land and part water, what the Muskogee (Creek) people are said to have deemed “trembling earth.” An Okefenokee advocate and veteran of swamp trips, Peck had never before seen the swamp live up to its name so well.

“I haven’t been on one that’s trembled,” she said.

Peat is what makes that trembling possible. It’s the foundation of the Okefenokee Swamp, and of wetlands around the world. And because the world’s peatlands — from Siberia to the Congo — stores thousands of year’s worth of carbon from wetlands plants, they serve as an important global hedge against climate change.

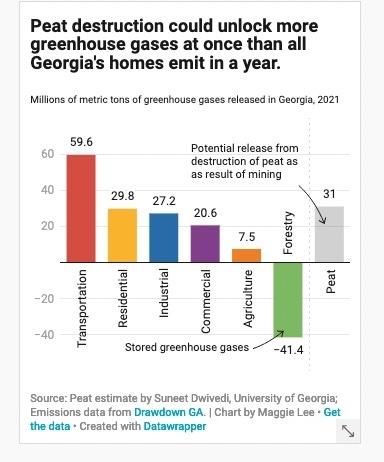

In fact, peat punches above its weight for climate stability. Peatlands cover only 3% of the earth’s surface but they store 30% of the world’s soil carbon. They even outdo forests, storing twice as much carbon on one tenth the land area on a worldwide basis, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service reports. The Okefenokee has tucked away at least 95 million tons of carbon, more than any other peatland along the Atlantic or Gulf coasts. That’s about the same as the net emissions from all Georgia’s homes, businesses and transportation in a year. And it’s more than all Georgia’s forests store over the course of two years.

Up close with peat

On this warm April afternoon, Lusk grabs a handful of peat floating on the water for a close-up look. Dark brown and full of stems and leaf parts, it resembles compost that’s not quite done. It’s spongy. He squeezes it and water pours out.

The peat smells like a freshly tilled vegetable garden, clean and earthy.

It builds up slowly, but at different rates in different locations. Studies by University of South Carolina researcher Arthur Cohen beginning in the 1970s showed that peat accumulates in the Okefenokee about an inch every 53 years.

At about a foot thick, the peat mat on which Peck wobbled took over 600 years to accrue. In some parts of the Okefenokee the peat is more than 9 feet thick and nearly 6,000 years old.

The Okefenokee’s peat is made of the same plants visitors to the swamp see today: mainly water lilies, ferns, sedges and pond cypress. Gardeners may be familiar with peat that’s largely sphagnum moss. It’s harvested from peatlands around the world and sold as a soil additive, though as scientists begin to understand the value of undisturbed peat, the practice is diminishing. A ban on the sales of it in the U.K. is set to go into effect next year. Likewise, European peatlands are increasingly being protected and restored after centuries of peat being harvested for use as fuel.

Peat formed by the decay of sphagnum moss tends to be dense, said Lorna Harris, Scientist and Program Lead – Forests, Peatlands, and Climate Change at the Wildlife Conservation Society of Canada. The Okefenokee’s peat is looser, what Harris calls “sloppy.”

“Fens and swamps can be very sloppy,” she said. (Fens are peat-forming wetlands fed by groundwater.)

That sloppiness allows Lusk to show off another of the swamp’s tricks. Standing by the side of the boat he pokes a wooden pole though the water and into the peat at the bottom.

“Those bubbles that are coming up, that’s methane,” he said. “So that’s what builds up under the peat. And when enough builds up it just floats it to the top.”

It smells like nothing. That’s because natural methane is odorless. The rotten egg smell of commercial natural gas, which is mostly methane, comes from the chemical mercaptan, added as a safety measure to warn of a gas leak.

Microbes within the peat eat the dead plant material and release methane deep down in the accumulated layers, Harris explained. In the Okefenokee, the buildup of trapped gas sometimes pushes the peat above it to the surface. That’s what happened with the trembling mat of peat on which Peck walked.

The Okefenokee has its own nomenclature for these peat formations. When they first appear at the water’s surface, these mats are called blowups. As they begin to recruit vegetation they’re called “barracks,” and when they have trees growing on them they’re called “houses.”

Seen from above they help form the mosaic that is the Okefenokee. Sara Aicher was lead biologist at the Okefenokee for 31 years, retiring in 2022. She first got a sense of the expanse of the refuge — the largest in the Eastern U.S. — by flying over it, and she was drawn to the Okefenokee for the wilderness she saw from above.

“A lot of refuges are in habitats that have been manipulated, or drained and they’re diked off,” Aicher said in an interview with The Current. “But you know, there’s dikes and impoundments and everything. That’s a lot of refuges are for waterfowl. And this was just not like that at all.”

Aicher is not a peat biologist per se — she trained as a wildlife manager. But she did know Cohen and helped with some of his studies before his retirement in 2011 and then death in 2020. She began collecting information about the Okefenokee’s peat in earnest because the refuge is being considered for nomination to World Heritage Status, a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization designation for places on Earth that are of outstanding universal value to humanity.

“You take for granted what you have, you look more just at the national level a lot of times, and how you fit into the string of refuges and things like that,” Aicher said. “But looking at a piece of ground in the world context is a little bit different.”

Aicher knew the Okefenokee was a blackwater swamp. Knew it was a largely intact freshwater wetland system. Knew it was a treasure of biodiversity with more than 850 different plant species, 200 bird species, 64 reptile species and 50 kinds of mammals. But in comparing the Okefenokee’s peat deposits with other areas and learning the increasing awareness of peat’s role in carbon storage she began to appreciate just how significant the Okefenokee is to the planet.

Worldwide peatlands

To understand the value of peat to climate stability, look no further than the fact that peat is basically very young coal.

“Coal is what peat will become given a few more million years,” Harris said. “Give it a lot longer in the ground, it will eventually become coal.”

Climate researchers have only recently come to understand the need to protect peatlands in order to protect the climate. The Global Peatlands Initiative was created in 2016 at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to save peatlands as the world’s largest land-based organic carbon stock and to prevent that carbon from being emitted into the atmosphere.

Peat’s low profile may be because many of the remaining peatlands, unlike the Okefenokee, are in remote areas, said Steve Frolking, a research professor at the University of New Hampshire who studies peatland carbon balance and long-term carbon accumulation.

“A lot of peatlands have been drained, particularly in Europe, and China and the U.S. for agriculture are disturbed in various ways, a lot for agriculture and development. So most of the remaining ones are in Siberia, and Canada and Alaska and the tropics, the Amazon basin and the Congo basin, and so they’re kind of out of the way, they’re not that well studied,” Frolking said.

There’s also the fact that historically, peatlands haven’t been economically important the way grasslands or forests or cropland has, Harris said. But recognition of their role as a climate stabilizer is prompting a second look. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has declared that “peatlands provide indispensable nature-based solutions for adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change.”

Elected officials like U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff of Georgia acknowledge the Okefenokee’s significance in combatting global warming.

“Wetlands like the Okefenokee are important carbon sinks that help reduce atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases,” Ossoff wrote in an email to The Current.

Scientists are beginning to tackle the issue of carbon accounting in the Okefenokee, the largest peat deposit in the North Atlantic Coastal Plain, which stretches from Texas to Massachusetts. The carbon stored within the swamp’s peat is equivalent to over 95 million tons of carbon dioxide, according to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Swamp advocates like the Aicher and the Georgia River Network’s Peck suspect that’s a woefully low estimate. They’re preparing a research paper for scientific review that could quadruple the estimate.

Peck and others have also been examining the expected effects of a proposed titanium dioxide strip mine near the southeast edge of the Okefenokee. Alabama-based Twin Pines Minerals has applied for state permits to mine nearly 600 acres in Charlton County and is awaiting a decision from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division. Twin Pines insists its mine will not alter the swamp’s hydrology, but academic researchers as well as hydrologists from the National Park Service disagree.

Peck wondered what the mine’s impact would be on the peat in the 26,000 acres of the southeast area of the swamp nearest to Twin Pines’ activity. University of Georgia hydrologist Rhett Jackson had already analyzed how much the water would be drawn down by the mining. Peck contacted Associate Professor and “climate guru” Puneet Dwivedi of UGA’s Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources to calculate how much carbon would be released from the swamp as the peat dried out and rotted upon exposure to oxygen.

“We did that exercise, and from the Twin Pines mine alone, it was 31 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, which is a third of what our entire state emits in a year,” she said, basing the comparison on net emissions calculated by Drawdown Georgia, a research-based initiative to help the state reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

The calculation highlights the fact that undisturbed peatlands function as a carbon sink, but damaged ones can be a climate disaster.

“Drainage and degradation are now having the largest impact on peatlands (and have had for the past couple of hundred years), with drainage/disturbance generally shifting peatlands from a slow carbon uptake to slow to moderate rates of carbon loss, and drainage/drying making peat more susceptible to fire and rapid loss,” Frolking wrote in an email. “In a fire peat typically burns down to the water table (saturated peat is too wet to burn) so not all peat is lost, but the system is further degraded.”

While wildfires are part of the Okefenokee’s natural cycles, climate change is already increasing the frequency of fire in the swamp. Large wildfires used to occur on about a 20-year cycle in the Okefenokee, Peck said. There have been five in the last 20 years. She warns that fires could be more frequent and severe if mining drains a portion of the swamp.

“The fires are mostly burn just across the top of the peat like a surface fire,” Peck said. “But it’s because the peat underneath it is wet. If the peat underneath is not wet, then the whole area of peat burns deep. The swamp, you know, is fire adapted, but it’s peat dependent. We want to keep that peat or we’ll lose the swamp.”

And gain unwanted carbon in the atmosphere.

“These peat fires can burn for months,” Peck says. “And if you think about 5,000 years of that organic matter disappearing, it’s irreversible.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.