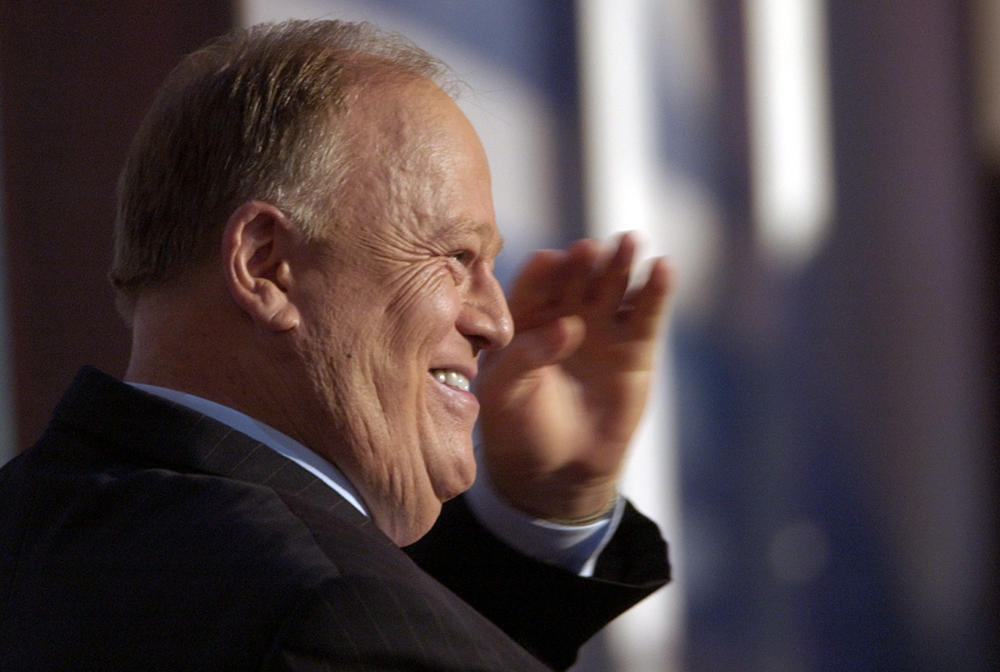

Caption

Former Georgia Senator Max Cleland salutes delegates before introducing Sen. John Kerry at the Democratic National Convention Thursday, July 29, 2004 at the Fleet Center in Boston, Mass. Cleland, who lost three limbs to a Vietnam War hand grenade blast yet went on to serve as a U.S. senator from Georgia, died on Tuesday, Nov. 9, 2021. He was 79.

Credit: Ed Reinke, AP