Section Branding

Header Content

The AG who prosecuted George Floyd's killers has ideas for how to end police violence

Primary Content

Updated May 23, 2023 at 7:02 AM ET

It's been three years to the week since George Floyd's murder.

Video captured how Derek Chauvin, who is white, used his knee to pin Floyd, a Black man, to the ground for more than nine minutes while Floyd pleaded for his life. Within hours, protests erupted in Minneapolis and then around the world.

When the local community lost faith in the county prosecutor, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz urged state Attorney General Keith Ellison to build the case against the former officers who killed Floyd.

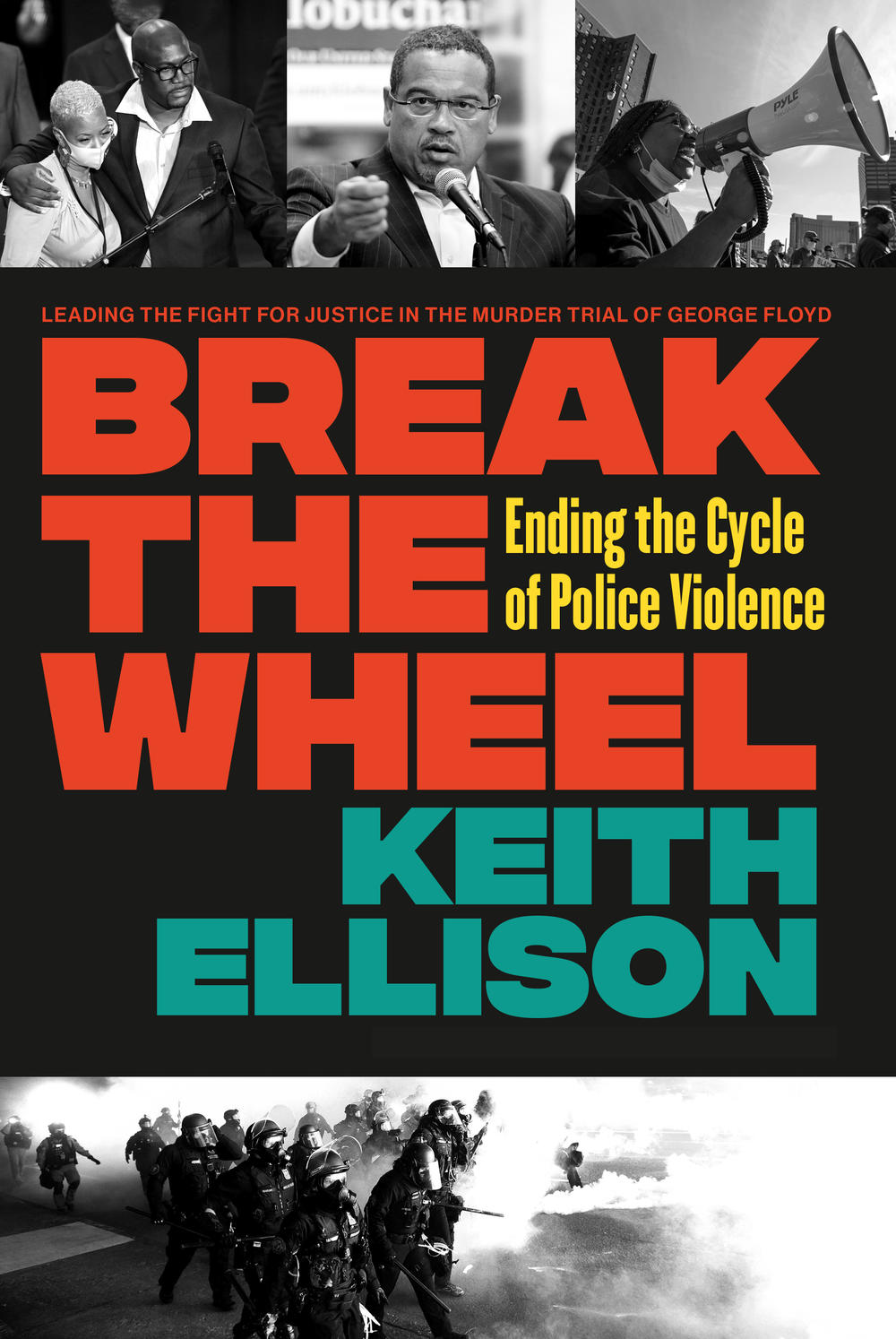

Ellison kept a diary of that process. And he's releasing it to the public in the form of a book called Break the Wheel: Ending the Cycle of Police Violence, out Tuesday.

In it, Ellison recounts how he cried when watching the video of Floyd's murder for the first time.

"For me, it was a gut check moment, one of those moments where you ask yourself, 'What am I about and what am I in this for?'" Ellison tells NPR's Leila Fadel. "And my answer had to be, we're going to do anything we can to try to make sure that the outcome is fair, just and right."

In an interview with Morning Edition, Ellison talks about lessons learned from the convictions of Chauvin for killing Floyd and three other former officers for aiding and abetting. And he recalls his hopes that outrage over Floyd's killing offered a possibility of ending state-sponsored violence against Black Americans.

"We have not gotten to the point where we've arrested this problem," Ellison says. "But I still believe that the George Floyd prosecution still offers a possibility if we muster the political will to bring it to a stop."

There have been other high-profile police killings of Black people since then, from the shooting of Jayland Walker in Akron, Ohio, last June to the beating death of Tyre Nichols at a traffic stop in Memphis, Tenn., earlier this year.

And the officers involved aren't always held accountable: Just last month, for example, a grand jury declined to indict the eight officers who shot Walker — while Myles Cosgrove, the former Louisville police officer who shot and killed Breonna Taylor in March 2020, was hired onto the force in a neighboring county.

Ellison says this is why federal police reform, specifically the George Floyd Justice In Policing Act, is so needed. (That legislation passed the Democrat-controlled House in 2021, but stalled in the Senate.)

"Sadly, these kind of things are likely to happen again before we bring this phenomenon to an end," Ellison says. "And we need other folks to help to know what happened so that they can make good policy choices."

For his part, he sees creating a historical record as key to eventually bringing an end to the pattern of police brutality.

"I hope somebody reads this book and says, 'This could happen to my town. Here's some things they did here that worked. Here's some things they did that maybe didn't work,'" Ellison says. "And we can use them to prevent and to stop this problem, to break the wheel."

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

On the importance of federal police reform

Congress needs to pass that legislation for the signal that the highest body of legislators in our country have said that this is a very serious problem that needs to be fixed. We need to prosecute criminal conduct whether the person has a badge or not. People need to be fired when they break the rules consistently. I don't think we're going to go from a bad situation to a perfectly good one overnight. And there are times when this is action that officers must take to preserve their own lives and others. But there are still far too many cases where, like the Tyre Nichols case and others, that just seem unnecessary and brutal and they tear the fabric of our society.

On the need for accountability across police departments

We need to have a national registry so that if you have an officer who has violated somebody's human rights, violated department rules, [they] cannot just go to another department and just start up there. And one prominent example is with the Tamir Rice case, where one officer was found to be unfit to serve in one Ohio police department and then goes to Cleveland and gets hired.

... I think that the recruiting challenge that policing as an industry is facing might have something to do with the fact that people like Derek Chauvin and Myles Cosgrove diminished the reputation of the profession. I think we'd have more success recruiting if people felt that their colleagues were going to be held to a high standard of professionalism.

On fixing the culture of police departments

There is this idea, this notion that I think is incorrect, that you have white officers killing Black people, and that is the model. In fact, we know that isn't the way it is. If you are a female officer or officer of color and you join that department, and if that department has a toxic culture, you are going to be pressed into it.

And so it's not the case that even a young Black man who joins a police department who might go in with the best of intentions is just going to change that institution if his [field training officer] is demonstrating the worst conduct — as [former Minneapolis police officer] J. Alexander Kueng's FTO was Derek Chauvin. Merely diversifying departments without real changes at the top, including cultural changes, you're just going to replicate the same results. And those changes have to do with accountability, with ridding the system of impunity. And just getting more officers of color or female officers is not a panacea.

On his narrow reelection win following Chauvin's prosecution

Folks who are connected to law enforcement unions spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to try to defeat me. They did it because they wanted to send a message that if you prosecute a member of law enforcement, you might be risking your job. And if I would have lost my election, that would have been too bad, but I would have had no regrets. But I don't want any prosecutor in the United States to ever have to say, I'm going to pursue justice ... or I'm going to look out for my own political interest, which would mean that I might back off.

I wanted prosecutors to know you can do the right thing, you're just going to have to survive some of these tough elections after some of these tough cases that you have to take. We want to break the wheel, but ... the reality is we're going to have to chip away at it.

The broadcast interview was produced by Ziad Buchh and Ana Perez, and edited by Jan Johnson and Reena Advani.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.