Section Branding

Header Content

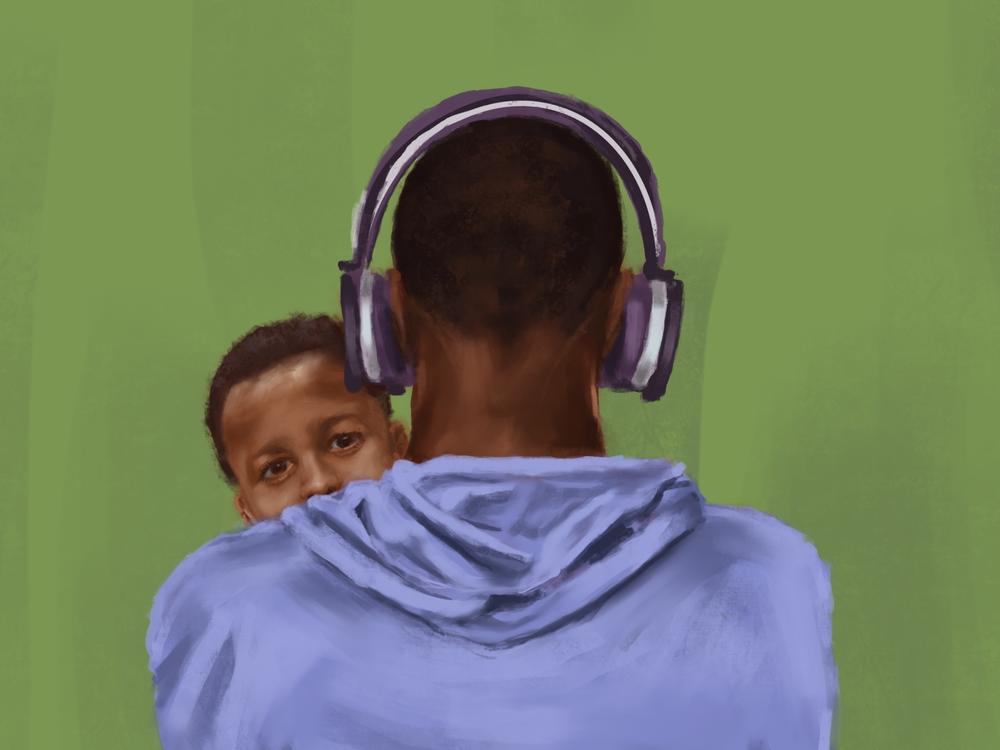

'He gon' get these beats 'n' rhymes'

Primary Content

This story was adapted from Episode 9 of Louder Than A Riot, Season 2. To hear more about Black masculinity, accountability and fatherhood, stream the full episode or subscribe to the Louder Than A Riot podcast.

ACT 1

Of all the hoods rap prepared me for, fatherhood ain't one of 'em. I've loved hip-hop for most of my life. It's been my livelihood for nearly half as long: I make a living by paying critical attention to the culture. But something about becoming a dad in the last few years pulled some of the wax out my ears. I hear rap differently now.

Multiply that times two, 'cause about a year ago, we added a daughter to the mix — and hip-hop heads tend to obsess over our daughters in the most oppressive ways. Like Chris Rock joking about a dad's only job being to keep your daughter off the pole. Or T.I. confessing to going on his teenage daughter's gyno appointments to make sure her hymen was still intact. When it comes to those baby girls, the patriarchy don't play. Meanwhile, we raise sons to be as bad as dear old dad.

All this season on Louder Than A Riot we've been looking inward, at how a culture created by the marginalized became such a marginalizing force to so many within it. At times, it's caused me to question myself, because there ain't no way to truly interrogate misogynoir in hip-hop without men taking some accountability. Not just for the past, but the future. So we don't turn our sons into survivors, and perpetrators, of the same fate.

My 3-year-old son has become a Biggie fanatic. He bumps B.I.G. on the way to school. He bathes with B.I.G. blaring in the bathroom. Sometimes he even requests B.I.G. while taking a dump. The fandom started with "Juicy." Now he's deep into the album cuts — and not the clean versions, either. My wife bought him a t-shirt with the Ready to Die album cover superimposed on the front, which he rocks religiously. But his growing obsession with all things Biggie is all daddy's fault. Every time he hears a new song, he has a habit of looking at me through the most earnest eyes and asking, "What's this song about?" It's almost like the question he's really asking is, "Daddy, explain the world to me." Maybe by the time he's able to hold a conversation for longer than two minutes, I'll have found the words to explain why Biggie is complicated in more ways than his internal rhyme schemes.

Fifty years after the birth of hip-hop and almost four years after my own son's birth, I find myself consumed by this question: How young is too young to begin talking to my son about rap?

It's kinda like deciding the right time to tell your kid the truth about Santa. Or sex. By the time my dad worked up the nerve to talk to me about the birds and the bees, I'd already memorized 2 Live Crew's "We Want Some P****." And the way Dad talked about sex — using the clinical verb "insert" to describe the act — was not the way Luke and them talked about it. His version was even shorter than the song. My dad and I didn't even live in the same house. Ice Cube, Too Short, Scarface — they lived in my head rent-free. They were the rappers who raised me. Especially when it came to how I thought about girls and, eventually, women.

Kiese Laymon, a genius of a writer I've long admired, has written a lot about growing up hip-hop in the South, and the sexual harm that often came with the territory. I spoke to him about some of that shared history.

"2 Live Crew, bruh — I went to the concert in like '87. It was 2 Live Crew, it was Too Short, and I was going through puberty," he told me. "I knew that the s*** they were saying about women was f**** up. I knew it was mean. And I knew they couldn't rap. But I also knew, at 12 or 13, that the album cover made my body feel things. And when they performed in Jackson, they had them dancers on stage — real live grown women shaking they ass. And then these men are talking about how these grown women ain't s***. There's a dissonance there."

2 Live normalized things for us that shouldn't be normal at any age. Before I knew anything about what could go down at high school skip parties, their lyrics inducted a generation of Black boys like me into rape culture: "See, me and my homies like to play this game / We call it Amtrak but some call it the train / We all would line up in a single-file line / And take our turns at waxing girls' behinds."

Every generation of Black men has to redefine masculinity all over again for itself. The hand-me-downs from our daddies' and granddaddies' past never seem to fit quite right. My generation overdid it: We took that blaxploitation-era machismo, added guns and gangsta grills, a fascination with pimpin', pushin' and playin', and packaged it for mass consumption. Never once realizing we were the product the entire time. Hypermasculinity had become a sword and shield Black men carried to ward off 400 years of fear, oppression, desperation. But when you weaponize yourself for protection 24/7, you end up causing the most harm to the ones closest to you. Even yourself.

"Before you can have a revision, you have to have a vision," Kiese tells me. "[We're] talking about the things we don't want to be replicated, but a vision is equally interested in what we do want to be replicated. Part of revision for me is just actually sitting in some of the harm I've done. But also you can drown in that, too. So that's why it's really important to think about who you want to be, as opposed to, like, who you don't want to be. I don't want to be harmful, but the harder question for me, Rodney, is who do I want to be out in the world?"

They say the universe is so vast that we all have alternate versions of ourselves floating out there. I found mine drowning at the bottom of a 40-ounce bottle when I was 19. He was everything I wasn't at the time: unleashed and unashamed. I dubbed him C-Mike. My hip-hop alter ego. The dude I became once I was finally outta my momma's house. I still wasn't old enough to drink, or think straight. But I could legally buy a box of Newports, vote for a doobie-smoking president who claimed he never inhaled and sign my life away to Uncle Sam.

Joining the Navy was supposed to be my great escape — a way to run from responsibility, expectation and all the other Black, lower middle-class hopes and post-civil rights dreams the generation prior had invested in me. They stationed me on an aircraft carrier of 5,000 men. We got paid to chock and chain fighter planes, but we clocked way more hours as hip-hop journeymen. Fishing out the hardest bars and deciphering rhymes was our closest thing to therapy. My best friends were ex-dopeboys, second-chance delinquents, teenage dreamers, stuck in that liminal space between adolescence and accountability — a space Black boys ain't granted for long. We bonded over Snoop and Dre weed anthems, "Bitches Ain't S***" ideology and Thug Life doctrine. We were politicians. We were philosophers. We were malt liquor guzzlers.

I stumbled back to the boat more times than I can remember, blacked out. Fragile egos took some of us out before our discharge date. A homie wound up in the brig when too much s***-talk over a spades game brought the knives out. And I fell asleep in my rack way too many cold nights, pumping Sade through my headphones and tucking my feelings under the covers so nobody could hear me humming "Love is Stronger than Pride."

I popped the piss test for smoking weed, a "zero-tolerance" offense. But the real reason I got kicked out of the Navy was because I got too good at pretending I didn't give a f***. Something about that masquerade felt like the closest thing to freedom for a younger me. The stamp on my discharge papers read "Other Than Honorable." A threat to the establishment. For me, there was some honor in that. Never mind that I'd barely saved a dime, or that I was going back home to my momma's house empty-handed: At least Ice Cube wouldn't think I was a sellout now.

After a year of living recklessly, my wake-up call came somewhere between Oakland and Atlanta, on a four-day Greyhound bus ride back to reality. De La Soul's Buhloone Mindstate was in my headphones the whole way home:

"I keep the walking on the right side

But I won't judge the next who handles walking on the wrong

Cuz that's how he wants to be

No difference, see

I wanna be like the name of this song, I am"

— De La Soul, "I Am, I Be"

ACT 2

The act of reshaping my own hip-hop identity started in earnest, maybe, around the time I settled into my career as a working journalist. I became the music editor of an Atlanta alt weekly the same year that T.I. got busted on federal gun charges, DJ Drama's studio got raided by federal agents and director Byron Hurt dropped his documentary Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats and Rhymes. The film was my first comprehensive look at how misogyny, homophobia and transphobia became pillars of rap's toxic culture; there's this classic scene where Busta Rhymes promptly exits the studio when Hurt starts asking him about homophobia in hip-hop.We covered Hurt's film, T.I.'s trial, Drama's arrest and Nelly's "Tip Drill" backlash that year. Matter of fact, we covered so much hip-hop that the editor-in-chief took me out to lunch one day to complain about all the rap — and rappers — taking over his music section.

Defending my editorial choices meant defending the culture. The racial politics were thick. But the gender politics at play were becoming harder to defend, even in my own mind.

Writer and cultural critic Jamilah Lemieux has spent years unpacking those politics. When she dropped "Dave Chappelle and 'the Black Ass Lie' That Keeps Us Down," her 7,000 pound essay in response to Chappelle's comedy special The Closer, it was bigger than "Roxanne's Revenge." I remember tweeting it out at the time and calling it "required reading for straight Black men" or something like that. The first response I got was some bruh saying Black men had no avenue to express our pain. "The story that we've always been sold about hip-hop was that hip-hop is Black men telling their truth," Jamilah tells me. "This is their side of the story. This is how they get to tell the world what they go through. And so for us to challenge that, we've been told, we're challenging your ability to speak freely and talk about your experiences. But what you all are saying is incredibly hurtful to us, and about us. And so, what does that mean? Am I to believe that we are so vile to them that we have somehow earned this loathing?"

They say misogyny is rooted in hatred. I've never thought of myself as a hater, least of all of Black women. I have loved them and been loved by them, in one regard or another, for my entire life. That love nurtured me, even when I didn't fully love myself.

But I've also loved hip-hop, with my whole entire soul, and I never saw those two things in such stark conflict until recently. It's forced me to consider my own complicity. I've thought about how I've contributed to misogynoir in ways I didn't realize earlier in my career, as a writer and editor who sometimes penned pieces — under the guise of celebrating women in rap — that only painted them further into a corner. Or hotepping before hotepism, with profiles that objectified women sexually or moralized over them exercising their own brand of sexual agency.

Putting ideas like this into the world influenced the way people read the art and actions of Black women, causing a particular kind of harm that's worsened as women have come to dominate the genre. And it would be hypocritical of me to ask why that is without questioning myself first.

"It's constantly a process," Jamilah says. "It's constantly a negotiation. And I think that in general, Black people have negotiated a lot to love hip-hop. ... There's this adherence to white male patriarchy that is deep in some of our men. Hip-hop is hyper-capitalist. It's about who's got the biggest bank account, who's got the biggest watch, who's the most visible? That's where success and freedom are measured. And so instead of searching for a version of revolution that includes all Black people, they're thinking of how they get to live and be like white men."

The fact that much of mainstream rap, for so long, lost or altogether lacked any kind of real intersectional come-up feels like a major fail. Instead we became a culture of exclusivity and exclusion — a billionaire boys' club, corporatized and commodified to death.

It reminds me of a line from an old Outkast album I still bump religiously. It comes near the end, like a fresh sprinkling of Southernplayalisticriticalracetheory, after nearly 60 minutes of post-adolescent posturing:

"If you think it's all about pimpin' hoes and slamming Cadillac do's

You probably a cracker, or a n**** that think he a cracker

Or maybe just don't understand"

– OutKast, "True Dat"

When Dungeon Family sage Big Rube said that, it took me years to understand. Rube was critiquing capitalism, or the crooked American system, as he called it. But he was also calling out Black men and our undying allegiance to it. Being a big ol' pimp became the modern-day remix on the slave master — but in blackface. Even the countercultural stereotypes we claimed as uniquely our own were just spin-offs of our regularly scheduled programming.

Like Audre Lorde said, "The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house." What we need are some tools that see racism and misogynoir as flipsides of the same oppression. But it's hard to construct that future when the toolbox you're working from is a hand-me-down.

ACT 3

"And to my partners that figured it out

Without a father I salute you

May your blessings be neutral

To your toddlers"

– Kendrick Lamar, "Father Time"

I've come to terms with the fact that I don't have a lot of things I can offer my son. I won't die with significant material wealth to bequeath him. I can't pass down any sort of athletic prowess that'll help him excel in sports. Even when I was a straight-A student and one of the smartest kids in my class, math stayed kicking my ass. Music is the only language I've ever been fluent in. It's still the most revolutionary art form in my lifetime, even though my relationship to it may be way more complicated now. At this point, my legacy is old baggage. It's full of dusty records and dustier ideals I picked up — through all my dads — about how to embody manhood.

My relationship with rap nowadays is a lot like my relationship with Black men in general. I call few friends, and call on those actual friends even less than that. As men get older, our connections to other men become less tangible. We get busy with life's responsibilities: building a career, raising a family, hiding from our emotions. We get hard, or try to steel ourselves. Not just against the outside world, but from our inner selves too. When I was young, me and my n****s bonded over hip-hop. Memorizing explicit lyrics. Reciting raps in the mirror like we wrote them. It was a release. But I stopped memorizing lyrics a long time ago. I don't dance in the mirror now. And the only raps I occasionally recite are the ones that make me feel like I'm C-Mike again. I never heard music the same after that. But maybe because I never had friends who made me feel music quite like that again, either.

"A lot of men are feeling that, bruh," Kiese says. "In listening you can hear people talk about a kind of loneliness. And I think part of that is some of us don't make space to touch and commune with other brothers and our friends. For me, my friendships with my brothers, that was love. And what did we do in those groups? We talked about hip-hop. Hip-hop, right at the core — in addition to being all of the f***ed-up things that the nation is — there's a textured love in there for me that I have not found anywhere else yet."

...

My son has this habit of calling me his best friend. It's cute. But it always makes me think about how that was a parental no-no to the generation before me. Our parents weren't our friends. Didn't want to be. Didn't pretend to be. And they had special ways of reminding us if we slipped up and forgot. But when he calls me his best friend now, part of me thinks about all the people I called friends growing up – all the rappers who schooled me coming up, all the people who I looked to, even more than my parents, to give me the game — and I think him seeing me as a friend might not be the worst thing in the world.

Teaching my son how to listen critically and empathically, how to hear the love and the lack in the music, how to distinguish the good s*** from the bull**** — even when the bull**** is that s***, feels like the work. Necessary work. But it's also the fun. And in the right hands, maybe rap can be a tool for teaching my son something it's taken me this long to learn. As long as he never stops asking his favorite question, "What's this song about?"

I see a softness in my son. The kid's 3 years old. He's supposed to be soft. But sometimes I see that softness and I'm embarrassed by it. Maybe 'cause it reminds me how soft I am, and how I spent half my life trying to camouflage it. I look at him and I see the kid that cries too long when he's hurting inside. I see him and I remember the look my dad used to give me when I did that.

I've tried to give him that look. But my son just keeps on wailing. The look doesn't work on him either. And I secretly take pride in that. Even as I fight back the urge to strip it away. I don't wanna make him hard. I don't. Not too hard. Hard enough to survive. But soft enough to live. Without being afraid. Or unforgiving. Or dead.

And I hope music can be a lifeline somehow. I know this problem is bigger than my one son. But it feels like the most meaningful work I can do. Something I can hold myself accountable for. Because the truth is: I need work too. I'll definitely have to unlearn some things about who I am and the person I imagine him to be. I'm also trying to leave myself open to whatever he has to teach me. Even if it's how to be softer.

'Cause the same way I gave my son blood and breath, he gon' get these beats n' rhymes. We Black. And rhythm is all we have that couldn't be stripped from us or stolen away. So he deserves every bit of that. It's his without asking. But he deserves to have it in a way that doesn't require him to lie, die or cause harm — to himself or anyone else.

What I've always loved about hip-hop is it's a self-regulating culture. We determine what's cool, what's corny, what's cap. We set the tone, take the temp and tell the time. That means there's space for the next 50 years of hip-hop to be a jammin'-ass course correction — a counter-revolutionary remix, intersectional and liberatory as all hell. Me and you, yo mama and your cousin, too. I think that's the textured love Kiese's talking about. And I wanna give that to all our children.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.