Section Branding

Header Content

John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy's fearless experiment sets a new album ablaze

Primary Content

A little over 60 years ago, the editor-in-chief of DownBeat magazine asked John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy a deceptively simple question: What are you trying to do? He rephrased slightly: What are you doing? The two saxophonists sat for a long 30 seconds before Dolphy broke the silence. "That's a good question," he said.

The DownBeat editor, Don DeMicheal, printed this exchange in the April 1962 issue, as part of a fascinating article headlined "John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy Answer the Jazz Critics." Regular readers of the magazine would have known precisely what provoked this gesture: a scathing review of Coltrane's quintet with Dolphy, decrying "an anarchistic course in their music that can but be termed anti-jazz."

1961 had been a prolific and pivotal year for Coltrane. That spring, his sleek, intriguing quartet version of "My Favorite Things," from The Sound of Music, became a breakout hit. But later that year, as he signed to a new label, Impulse! Records, he wasn't putting a premium on commercial success. Instead, he was exploring new sounds and configurations, often testing ideas on the bandstand. One such idea was the addition of Dolphy, a wildly original voice on both reeds and flute, and a close personal friend.

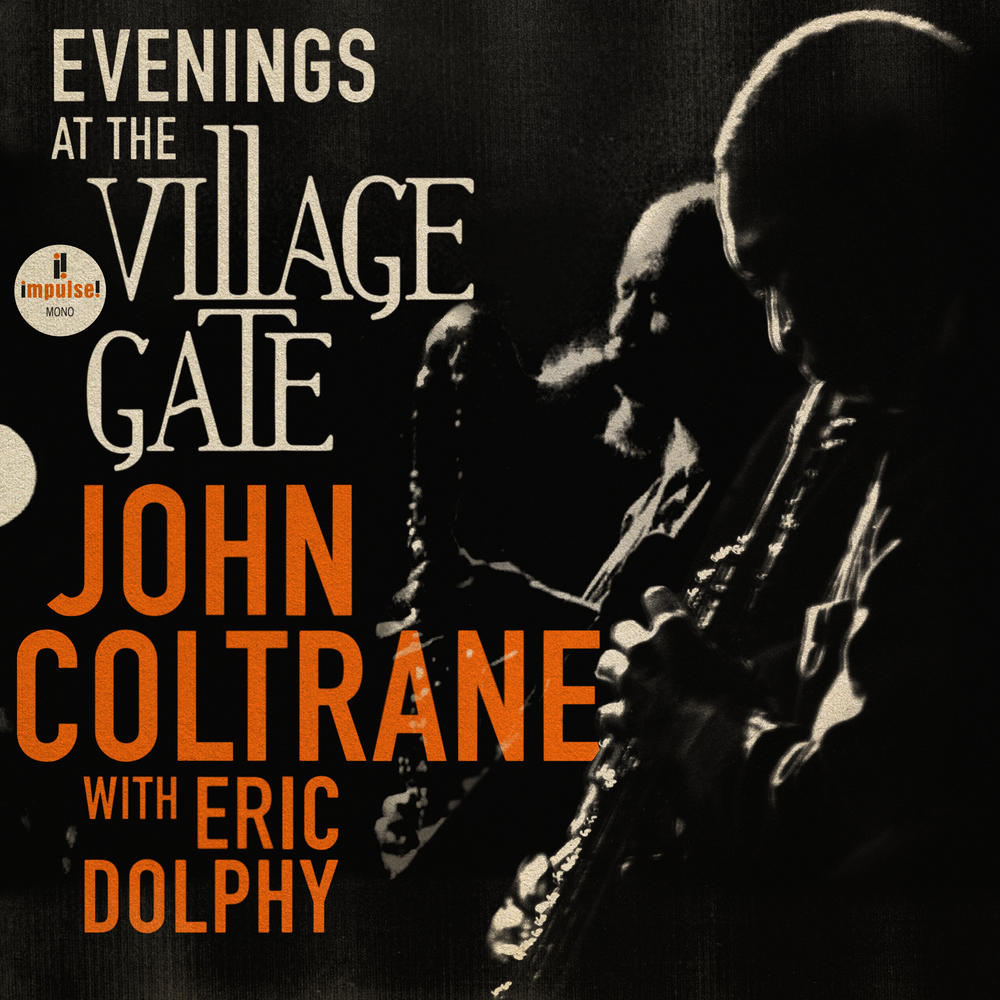

The intrepid depth of their musical rapport takes center stage on a stunning new archival release, Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy, which Impulse will release on July 14. Tomorrow the label will share a preview track, "Impressions," featuring Coltrane on soprano saxophone and Dolphy on alto saxophone and bass clarinet — along with drummer Elvin Jones, pianist McCoy Tyner and bassist Reggie Workman, who together make the song feel something like a runaway train. (Until then, you can hear it — exclusively — here.)

"Any time that we worked with John," Workman, who is a few weeks shy of 86, tells NPR, "you could always hear transition in his music." This was maybe never truer than it is here, in a recording made during a month-long residency in late-summer of 1961. Evenings at the Village Gate actually opens with a version of "My Favorite Things," and closes with the droning, polyrhythmic churn of "Africa." Coltrane was in the process of reinventing his language, and by extension the language of jazz.

"He was growing into a place where he did not want to be inhibited by the steps and the changes that were prescribed by certain structures," Workman says, adding: "He wanted us to be about a chant."

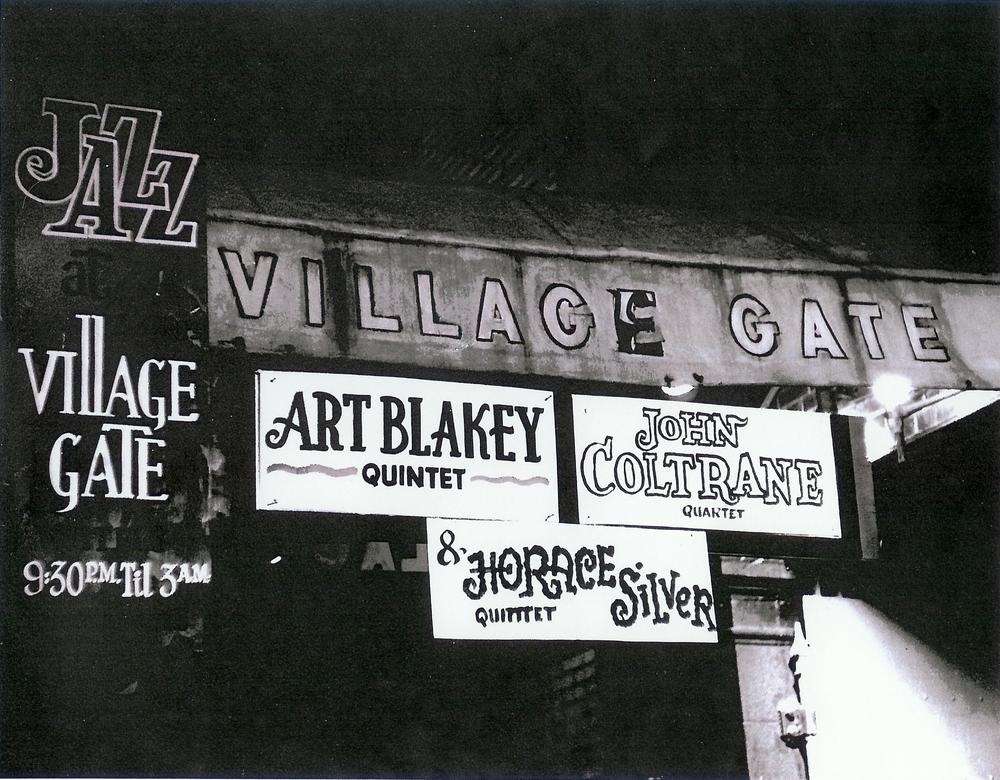

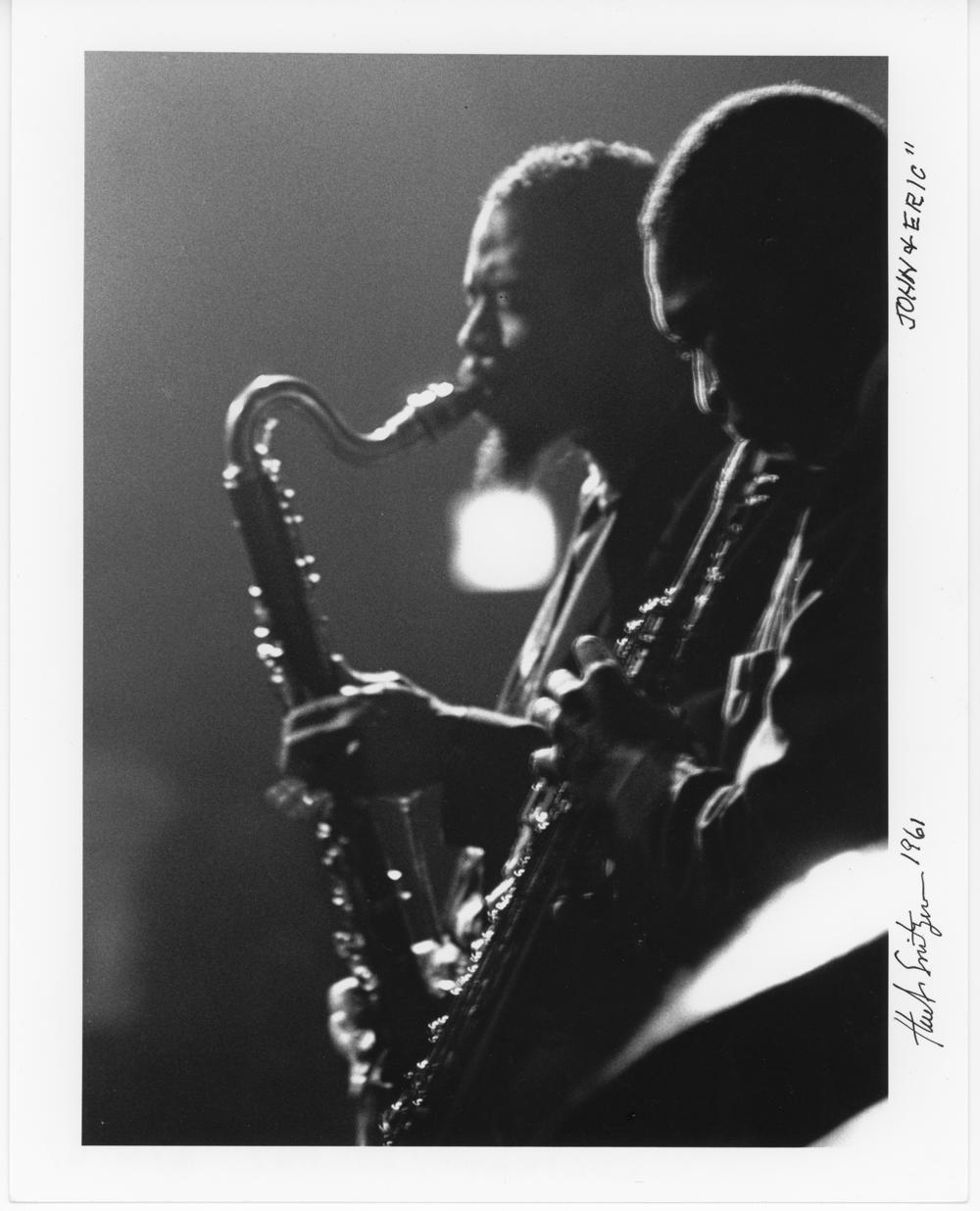

The Village Gate was a large basement room with a growing reputation in 1961, home to folksingers and comedy acts as well as artists like Nina Simone. Coltrane worked there in August as part of a triple bill, alongside groups led by drummer Art Blakey and pianist Horace Silver. (A photograph of the club marquee by Herb Snitzer shows Coltrane billed with a quartet, underscoring how recently Dolphy had joined the fray.)

The Gate had a state-of-the-art sound system, installed by an ambitious young engineer named Richard Alderson. One night during Coltrane's run, Alderson decided to test the system by capturing the band, using a single RCA ribbon microphone suspended above the stage, with a line running to a reel-to-reel tape recorder. The tapes were never intended for public consumption, and unauthorized in any case, so Alderson set them aside. They found their way to a collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, where they were recently rediscovered by a Bob Dylan archivist.

For Coltrane admirers, jazz historians and anyone intrigued by the experimental end of improvisational music, Evenings at the Village Gate will represent not only a welcome new find but also a link in a chain. The Coltrane-and-Dolphy frontline was short-lived, in part because it faced such strong headwinds from the jazz establishment, but it did leave behind a major testament: Coltrane "Live" at the Village Vanguard, recorded at a different Greenwich Village club in November 1961, the same month that their unruly output jarred loose the indelible phrase "anti-jazz."

Those Village Vanguard tapes, which later yielded a monumental four-disc set, amount to one of the most mysterious and thrilling documents in jazz history. A couple of years ago, Ben Ratliff, author of Coltrane: The Story of a Sound, placed this music within a cultural context of "ambivalent possibility," in a vivid essay for the Washington Post titled "John Coltrane and the Essence of 1961." He observes: "The music sounds post-heroic and pre-cynical; interestingly free from grandiosity; full of room for the listener to find a place within it and make up their own mind."

Last week, after hearing the version of "Impressions" from Evenings at the Gate, Ratliff elaborated on this idea. "It's very hard to label or encapsulate, but it's just so ferociously full of life force," he said of the performance. "The musicians know how good this is, and they know how exciting it is — but beyond that, they don't really know much, and it hasn't been called anything yet. There's a lot of the unknown here."

What came next for Coltrane was the most stable period of his career, as he solidified the personnel of his quartet — Tyner, Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison, who can be heard on parts of the Village Vanguard corpus — and made venerated albums like Crescent, Ballads and A Love Supreme. Parting ways, Dolphy refocused on his own visionary music, making strong statements until his tragically untimely death, of a diabetic coma, in 1964. (Coltrane died only three years later, of liver cancer.) The last several years have brought revelatory archival releases from both saxophonists, but Evenings at the Gate is a window onto the early bloom of their collaboration, when it must have felt like pure possibility to all involved.

The 80-minute album — which will be released in physical formats with illuminating liner essays by Workman, Alderson, Grammy-winning jazz writer Ashley Kahn, and saxophonists Branford Marsalis and Lakecia Benjamin — seems guaranteed to reignite conversation about an incipient phase in Coltrane's restless evolution. And it's worth recalling part of the answer he finally gave DeMicheal, for the piece in DownBeat.

"I think the main thing a musician would like to do is to give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things he knows of and senses in the universe," Coltrane said, sounding not the least bit defensive. "That's what music is to me — it's just another way of saying this is a big, beautiful universe we live in, that's been given to us, and here's an example of just how magnificent and encompassing it is. That's what I would like to do. I think that's one of the greatest things you can do in life, and we all try to do it in some way. The musician's is through his music."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.