Section Branding

Header Content

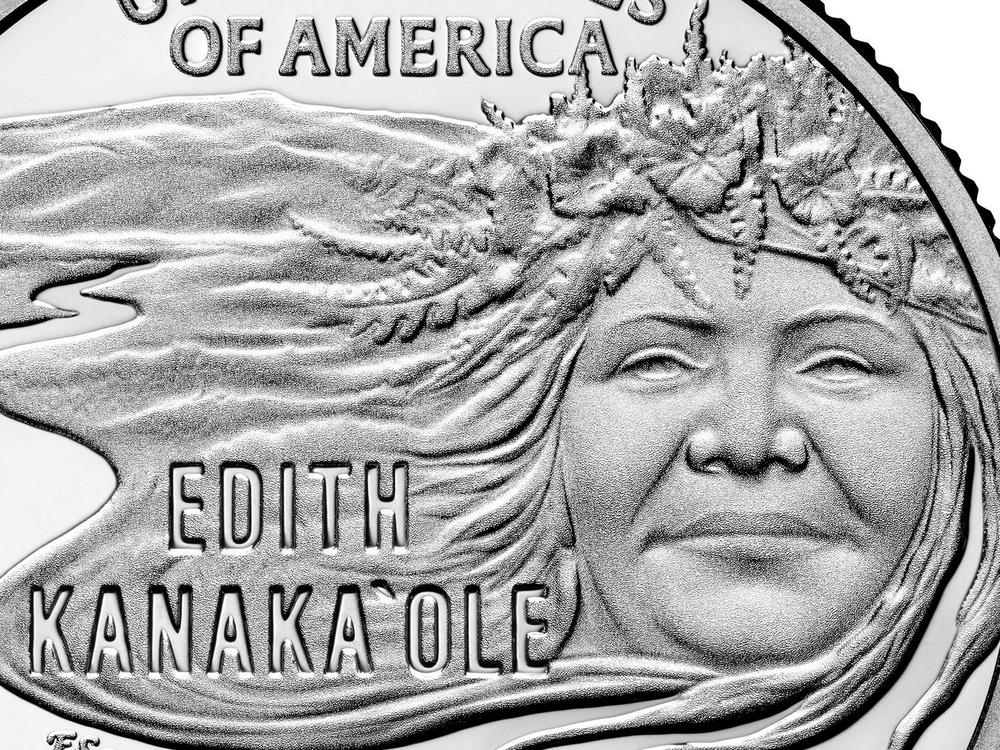

Edith Kanaka'ole is the first Hawaiian woman to grace a U.S. quarter

Primary Content

For the first time, the U.S. Mint is featuring a Native Hawaiian woman on a quarter. Edith Kanakaʻole was a Hawaiian cultural icon, teacher and composer.

The Edith Kanakaʻole Quarter is the seventh coin in the American Women Quarters Program, honoring pioneering women who've helped shape our nation's history and pave the way for others.

The U.S. Mint began shipping the new quarters on March 27.

"Through hula and chanting, Edith Kanakaʻole preserved the history, knowledge and heritage of the Native Hawaiian people," said Kristie McNally, U.S. Mint deputy director, speaking at the celebration of the quarter's release in Hilo, Hawaii on May 6. "Her tireless efforts teaching environmental conservation to future generations ... has made her a role model for all Americans."

During the Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance of the 1970s, Kanaka'ole was a dynamic force in reviving the Hawaiian language, hula and chant.

Fondly known as "Aunty Edith," she was born in 1913, on the Island of Hawai'i. She died in 1979, at the age of 65.

"We celebrate my grandmother every day through what we do," says Huihui Kanahele-Mossman, executive director of the Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation, noting that her grandmother was a tenacious Hawaiian woman who had no desire to let go of who she was. "Just her being this Native Hawaiian woman who refused to let go (of) her language, who held on to the fact that hula and oli (chant) is necessary as a part of the lifestyle of Hawaii."

But those practices were almost lost after a group of American and European businessmen, backed by the United States, overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy in the 1890s. The Hawaiian language was soon banned in government offices and public schools. And over the decades, other traditions were suppressed.

"Some of our people felt sorrow, maybe even shame for that loss," says Jon Osorio, a Native Hawaiian musician and historian. "I knew I grew up thinking that Hawaiian was completely gone from all households, because it was gone in ours. But it wasn't."

When he was 20, Osorio studied Hawaiian with Aunty Edith for one semester at the University of Hawaii at Hilo.

He's now the dean of the Hawai'inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. "Had it not been for folks like Edith Kanaka'ole there would have been no expertise to turn to. ... They are these gentle, loving — 'cause she was that way — earnest reminders that our ancestors were amazing."

Aunty Edith's teaching continues to inspire many of her students such as Puakea Nogelmeier, who studied hula and chant with her.

"She was criticized for teaching deep culture to a group that wasn't all Hawaiians," says Nogelmeier, who is white. "In her mind, it was very important that if you want knowledge to live on, you teach those who are interested. And she said, 'I know you all care, and you will be willing to carry it forward.' "

After retiring from teaching Hawaiian language for more than 30 years at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, Nogelmeier is still carrying it forward. He now runs a nonprofit called Awaiaulu, training people to interpret historical Hawaiian documents.

These days, he still recites a chant Aunty Edith once taught him to grant wisdom. A few words from that chant, "E hō mai ka ʻike," are now inscribed on the new quarter.

Photographer Franco Salmoiraghi made the image of Aunty Edith that an artist used for the coin. As they entered Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, he recalls how much she enjoyed the sounds of the forest, including the birds. "She was happy because she hadn't been out in a beautiful place like that in two or three years because she was so busy teaching."

Salmoiraghi was photographing Aunty Edith with her daughters, Pualani Kanahele and Nalani Kanaka'ole, for an album of the chants of Pele, the goddess of the volcano, recorded in 1977.

His favorite photo shows Aunty Edith chanting in the koa forest at Kīpukapuaulu. "Because it's not just the photograph, it's her. And it's all the energy that came from her, and all the people that she has taught over many years."

Later, Aunty Edith called the photo: "Ulu A'e Ke Welina A Ke Aloha." In English that means: "The Growth of Love is the Essence Within the Soul." Salmoiraghi recalls her telling him, "Whenever you use that photograph, I want you to use the title."

On the coin, Aunty Edith is wearing a lei po'o (head lei) with her hair flowing into the Hawaiian landscape.

Edith Kanaka'ole cared for the planet. You can hear it in her music and in a PBS Hawaii television special, "Pau Hana Years"... singing her beloved song "Ka Uluwehi O Ke Kai" ("Plants of the Sea"). Musicians still perform her songs today.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.