Section Branding

Header Content

This WWII battle wasn't against Nazis. It was between Black and white GIs in England

Primary Content

BAMBER BRIDGE, England — In the early 1980s, a Black maintenance worker in northern England noticed what he thought was termite damage in the wooden facade of a bank.

"I flippantly said to my colleagues, 'You've got big termites!'" Clinton Smith, now 70, recalls. "And they looked at me with complete dismay and said, 'No, they're not termite holes, lad — they're bullet holes.'"

They were bullet holes from a deadly World War II battle in Bamber Bridge, a tiny village in the northern English county of Lancashire. What surprised Smith most was that this battle wasn't against the Nazis. It was between Black and white U.S. soldiers stationed nearby.

When American troops deployed to Europe to fight Hitler, they brought Jim Crow with them. And when Black soldiers stationed in Bamber Bridge stood up to the racism and discrimination, one of them was shot dead, and more than 30 others were court-martialed for mutiny.

Eighty years later, they have yet to be exonerated.

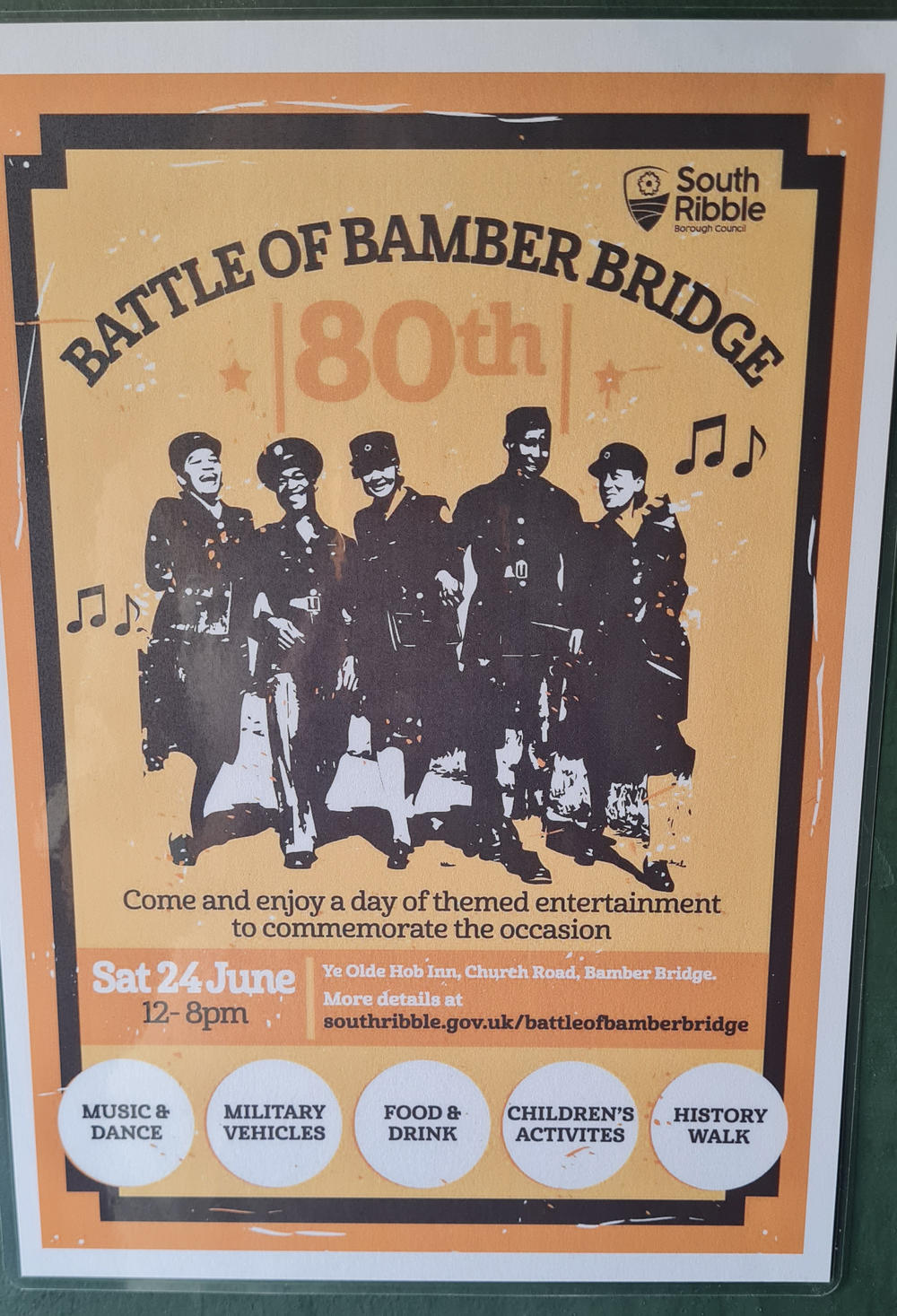

The Battle of Bamber Bridge — which took place 80 years ago this weekend, on June 24-25, 1943 — was a precursor to battles that would unfold on American streets for decades to come, during the Civil Rights era. It horrified the mostly white local villagers, who were unaccustomed to segregation and had befriended their Black guests. But because of wartime censorship, the battle was virtually unknown outside the tiny English village where it happened.

Smith, shocked by what colleagues told him about the origin of the bullet holes he'd spotted that day, vowed to change that — and has spent the past 40 years doing so.

The U.S. military was racially segregated

It wasn't until 1948 — after the war — that the U.S. government banned segregation in the armed forces. Before that, the military largely kept white and nonwhite soldiers apart. Military police were tasked with enforcing segregation rules — even while deployed abroad in the United Kingdom.

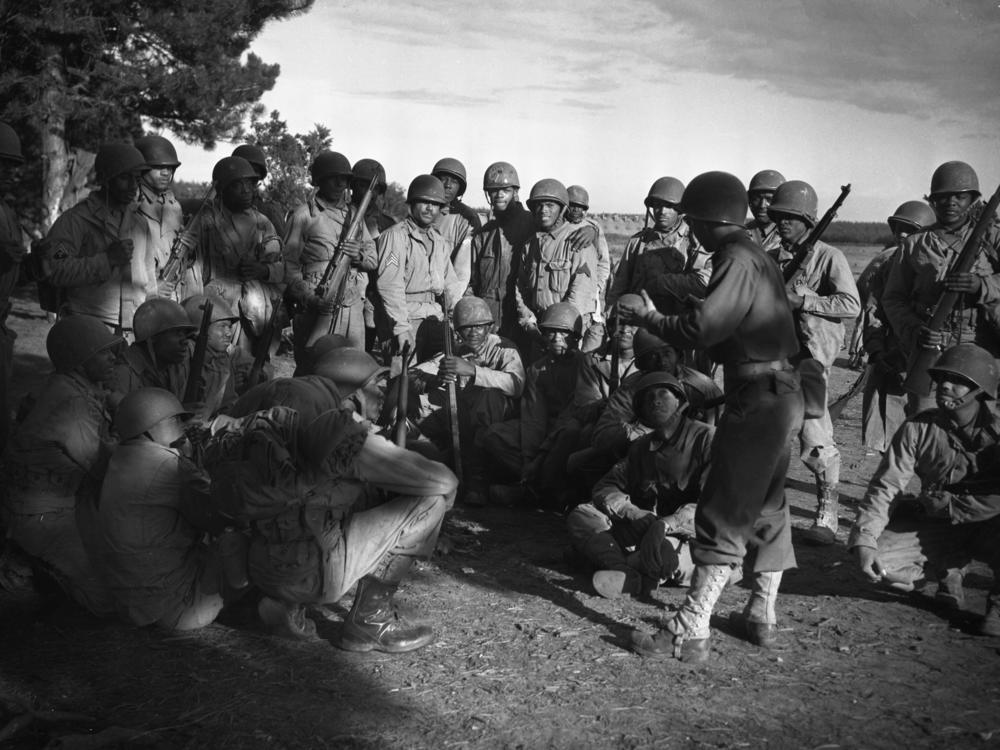

"In many places, the Army instituted a policy whereby white troops could go into town Monday, Wednesday and Friday and Black troops could go Tuesday, Thursday and Saturdays — to keep them apart," says Gregory Cooke, a Black historian and educator from Philadelphia who helped make a 2013 documentary called Choc'late Soldiers from the USA, about Black U.S. soldiers who fought in World War II.

During the war, Black troops who volunteered for combat roles often had to give up their rank and take a pay cut.

"The Army did not want a Black sergeant commanding a white private," Cooke notes.

For his film, he interviewed Black troops who came from the American South, where there had been lynchings — and deployed to Britain, where they were not in danger of such attacks. He says Black veterans told him that for the most part, "white Brits treated Black Americans as Americans, as allies, as equals — and as human beings."

That was especially true, Cooke says, in the little village of Bamber Bridge, population just 12,000. In 1943, it became the temporary wartime home of the U.S. military's 1511th Quartermaster Truck Regiment, a logistics unit staffed by Black soldiers and commanded by white officers. Because of segregation rules, the latter were housed separately, in the nearby city of Preston.

So it was the Black members of that unit whom the locals got to know best.

"They brought their [Black] culture with them, and their dance, that wicked Lindy Hop!" says Chris Lomax, mayor of South Ribble, the borough that includes Bamber Bridge. "We loved it in this country and we joined in."

Tension had been building between Black and white U.S. soldiers in Bamber Bridge

Days before violence broke out in Bamber Bridge, the U.S. experienced some of its worst race riots to date, in Detroit, from June 20-22, 1943. Dozens of people, mostly Black, were killed. In the days that followed, news of those riots reached Black soldiers deployed abroad — and it contributed to their frustration.

"There was an idea that we should be fighting for democracy at home and abroad, but our situation isn't improving. It's bad at home and it's bad here," says Alan Rice, a Black studies expert at the University of Central Lancashire. "[Black soldiers] keep getting stopped by the military police, and there's also the deep fear of miscegenation in the American military police and the white officer class — who just see it as an incredible danger, the fraternization that's going on between Black soldiers and white women from the local community."

(This was the era of lynchings in the U.S. of Black men like Emmett Till, if they were perceived to have made any sexual advances toward white women.)

In Bamber Bridge, all these tensions erupted into violence at a 17th century thatched-roof pub called Ye Olde Hob Inn. It was a popular watering hole where American troops used to drink with locals, around the corner from the Adams Hall Army camp, where Black U.S. troops stayed.

This account of what happened next is based on NPR interviews with historians, activists and Bamber Bridge residents, some of whom are descendants of witnesses to the battle, as well as archive footage of interviews with those witnesses.

Shots ring out in Bamber Bridge

On the night of June 24, 1943, Pvt. Eugene Nunn, who was Black, returned to Bamber Bridge after driving a military supply truck to nearby Manchester. Around closing time, he stopped for a drink at the pub, while he was still in his field uniform. Two white military police, Cpl. Roy Windsor and Pfc. Ralph Ridgeway, tried to reprimand Nunn for not wearing his dress uniform.

"He's in the wrong uniform, he's got a bottle in his hand — and he's Black," says Rice, the historian.

When the military police confronted Nunn at the pub, fellow Black soldiers and white villagers both rushed to his defense, yelling at the white officers. Nunn hadn't done anything wrong, they said. A crowd of about a dozen people formed, and the two white officers were outnumbered, so they retreated. Then someone threw a beer bottle at them.

"The court-martial transcripts spend more time on the amount of beer covering the American military policemen than they do with the subsequent death and injuries," Rice notes. "I think that says a lot."

The white officers vowed to return with reinforcements — and did so, with a machine gun mounted on their Jeep.

Meanwhile, Black soldiers retreated to their barracks, deliberated about what to do, and then decided to raid the local armory. They then confronted the white military police on Station Street, the main thoroughfare in Bamber Bridge.

But before that, Black soldiers "actually went back along the street, advising the locals with whom they'd built up a good relationship to stay indoors because there's going to be trouble," says Smith, the former maintenance worker who now heads the Preston Black History Group. "That's the relationship that they had."

It's unclear who fired first.

At least 400 shots rang out in Bamber Bridge that night, ricocheting down Station Street for five hours. Eunice Byers, who at age 106 is the battle's last surviving witness, recalls watching gunfire outside her window that night.

When the smoke cleared on the morning of June 25, 1943, a Black soldier — Pvt. William Crossland — lay dead in the street.

The price paid for Pvt. Crossland's death

The U.S. military said Crossland died in crossfire. Witnesses said he was shot in the back. He is buried in an American military cemetery in Cambridge, England, with no cause of death listed.

"Sometimes the most important deaths are not the unknown soldiers. They're the soldiers whose narratives tell us so much about the place we were in and the place we are now," says the historian Rice.

Thirty-five of Crossland's Black comrades were court-martialed, and 28 were convicted of taking part in what the U.S. military labeled as a mutiny. They were given prison sentences of three months to 15 years in prison.

Some later had their sentences commuted, so the military could keep them deployed through the end of the war — when it desperately needed the troops.

But they have never been exonerated.

In 1945, when the war ended, the Black convicts of Bamber Bridge returned home as part of what America calls its "greatest generation." They were unlikely to advertise having been involved in what the military called a mutiny, at a time of patriotic fanfare and celebrations about winning the war.

Cooke, the U.S. historian, has been searching for survivors. About 20 years ago, he managed to find just one — an elderly Black veteran living in Colorado.

"And he refused to talk to me about it. Our conversation lasted like no more than two minutes. People in his family may not have known. If he was court-martialed, it's not something he'd come back and voluntarily talk about," Cooke explains. "I got in touch with him 60 years later, and it was probably like reopening a wound for him."

Survivors of the battle would be at least 100 years old by now.

Healing the wounds of Bamber Bridge

The U.S. military has come a long way since segregation. It now has Black officers in its senior ranks, including generals. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin is Black. So is President Biden's nominee to be the next chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

But it is the residents of Bamber Bridge, not U.S. military officials, who have led a push for justice for the Black Americans who briefly lived here — and for the one who died.

"It was about right and wrong, about working-class solidarity," says Danny Lyons, 38, a local welder who recorded oral histories of his elderly neighbors in Bamber Bridge, who remember the battle. A short film by Lyons will be screened during commemorations for the 80th anniversary this weekend.

"You've got [Black GIs] coming over here, they were away from home, they were missing their families, they were fighting the war against fascism — and they've got all that stuff going on at home," Lyons says. "Basically it's about right and wrong."

Another person who's been pushing for justice for the Black convicts of Bamber Bridge is actually a representative of the U.S. government.

"This story gets told whether we're a part of it or not. So let's be a part of it," says Aaron Snipe, spokesperson for the U.S. Embassy in London. "We're a strong enough democracy to tell the entire story."

Snipe, who is Black, will represent the U.S. government at an academic symposium about the Battle of Bamber Bridge this Friday, on the eve of its 80th anniversary.

"My grandfather was alive during this time period, he worked on a military base in the United States where German prisoners of war were held, and he used to tell us stories about how the German prisoners of war were treated better than many of the African Americans who worked on this base," Snipe says. "So this is part of our history."

Those who fought in Bamber Bridge may have gone to their graves with the story of their alleged mutiny. So their descendants may know nothing about it. But the names of those Black men are still well-known to villagers in England. They will be remembered in a ceremony on the Bamber Bridge village green this weekend.

"Pvt. Nunn, Pvt. Ogletree, Pvt. Wise, and of course William Crossland. There's an awful lot of potential families out there and they've got a lot to be proud of," Rice says. "Their ancestors stood up against the racism of a segregated army, and also made a great impression on local people here who were very proud to have them in their town."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.