Section Branding

Header Content

He walked away from his evangelical roots to escape feeling suffocated

Primary Content

We all want to feel safe when we're growing up. And in an attempt to make kids feel safe, parents and other adults can sometimes circumscribe a child's life so that they don't come into contact with ideas or people who might make them feel unsafe in some way.

I know that was part of the reason my parents sent me to a Baptist elementary school. Yes, they wanted me to have a religious education. But they also wanted to know that, for at least six hours a day, I'd be in a place that reflected their own Christian values. Values they believed would make me a better person, and would keep me safe from the temptations and moral depravity of the secular world.

In fifth grade, they moved me to the public school, and it felt just totally wild to me. I could wear pants instead of dresses. Kids talked back to teachers, and the really bad kids wrote curse words on the back of the seats on the bus. I remember saying a prayer for one of them because I was convinced that he was damned to hell after that.

It was definitely a transition, but I figured out how to navigate myself outside of my little Baptist school bubble. And at that time, it's what my parents intended. They knew I had to learn how to operate in the real world – full of people with different values and perspectives and life experiences.

Jon Ward grew up in a more isolating corner of Christianity. He was raised in an evangelical church in Virginia that defined his life, his friends, his family – his whole identity. He was taught never to question the teachings of the Bible, or the judgment of the men who led his church. And he was discouraged from ever engaging in the world outside his religious community.

Jon had other plans though. After college, he decided to pursue a career in journalism. It was a choice that would fracture his family. Through his work as a political journalist, Jon learned how to interrogate assumptions, how to question authority, and eventually that meant questioning the church he grew up in — and leaving it altogether.

Jon Ward wrote a memoir about this experience. It's called Testimony: Inside the Evangelical Movement That Failed a Generation.

I wanted to understand what that choice to step away looked like, and the consequences of living with it.

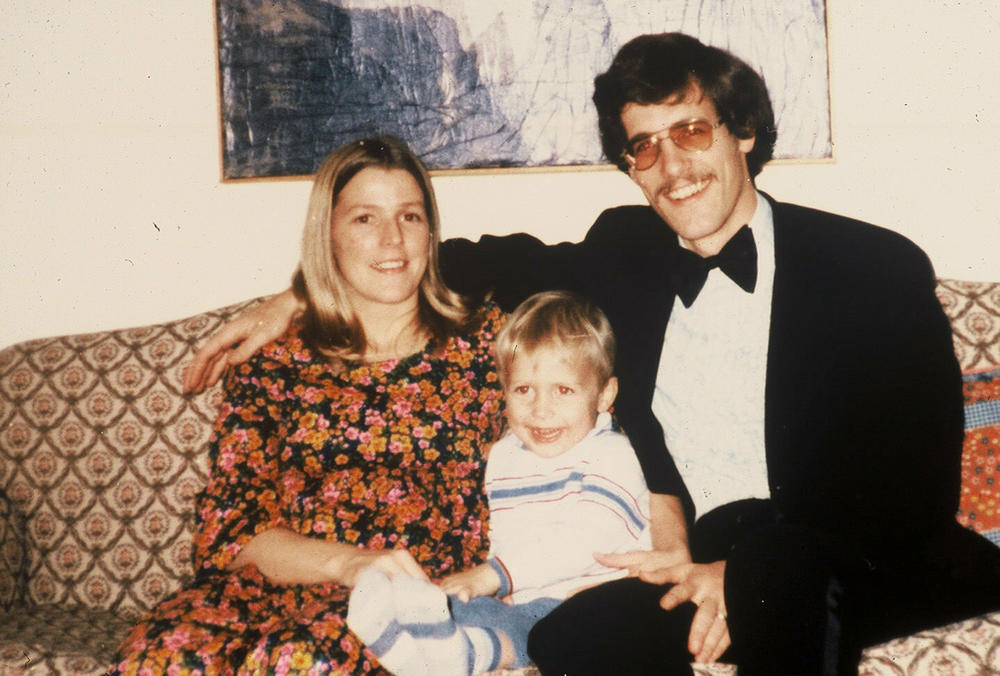

Ward's story begins with his parents. They were spiritual seekers. His dad had been a Catholic, his mom a disenchanted Presbyterian, and they were looking for something more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jon Ward: My parents were both caught up in something called the Jesus Movement or the Jesus Revolution, where a lot of people were looking for something fresh and new in religion. I think they were also disenchanted with the way the country had gone during the late '60s.

This new form of Christianity was very informal, a lot of hippie culture involved. They began holding Bible studies in the D.C. area that became very popular. The style was kind of a rock and roll worship service with a full band and then some dynamic preaching. My dad was one of the leaders of this group that was meeting and his high school best friend C.J. Mahaney was one of the top leaders. So that's the world I was born into in 1977 and I was the first infant dedicated at that church.

Rachel Martin: Dedicated, like baptized?

Ward: No, they might have sprinkled some water on our heads but it was pretty informal. Like, the parents go up on stage and pray over the child essentially.

Martin: You write that the worst thing you could be called by an adult member of your church community was "lukewarm." Can you explain that?

Ward: This is such an important topic. They would quote a passage of scripture which talks about God literally spitting you out of his mouth if you are lukewarm. It was often used, especially in youth group culture, to essentially communicate to us that we needed to be all in and on fire for God.

Martin: And there was a real priority given to the emotional experiences, right?

Ward: Yeah. It felt like you had to get caught up in the emotional fervor of the church to not be viewed as lukewarm.

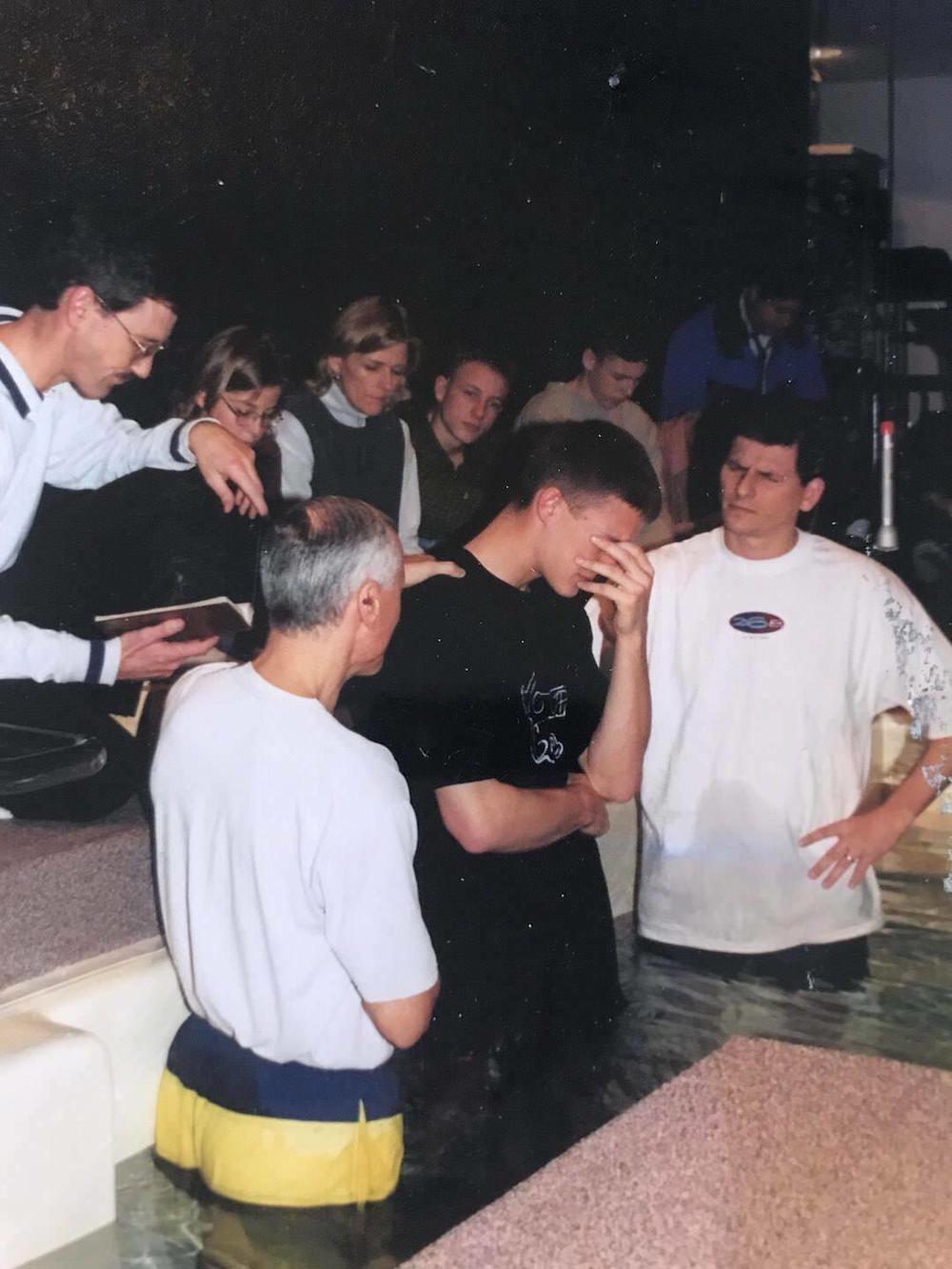

Martin: But it started to feel false to you. Can you tell me about the time that the minister of your church placed hands on you and explain what that means?

Ward: Sure. I mean, the emotional aspect of it, we conceived of authentic faith as having very strong emotions for God. The moment you referred to took place in the mid '90s. Our church, like a lot of churches in the country at that time, was having services where they would invite people up to the front and people would be prayed for and then people would fall down all under the auspices of a move of the Holy Spirit. And in late high school or early college I went up to be prayed for. My parents I believe were with me and the same pastor who my dad was friends with in high school, C.J. Mahaney, came up and prayed for me. And at a certain point I just felt like it had been going on for a while and I didn't feel anything outside of my body.

Martin: So he's putting his hands on you and you're supposed to be feeling something.

Ward: Yeah. So I'm waiting for something to happen to me and he kind of nudged my forehead as if a signal to say, "Now is the time for you to go down."

Martin: Wait, he nudged you?

Ward: Yes. I felt pressure to make it happen. So at a certain point I fall to the ground, people would catch you if that happened, and as I'm in the process of going to the ground I believe I had this feeling of shame that I had faked it.

Martin: So where did your faith move from there? There was a juncture where you decided to not be lukewarm anymore and to go all in.

Ward: Right. Two years later, I've been in college for two years and I've started to experiment with the really crazy lifestyle of occasionally having a beer.

Martin: Because that was not allowed, it was taboo to drink alcohol even though you were of age, right?

Ward: Yeah. I felt at the time that God moved on me to grab hold of me and to stop me from going down a path of partying and all that. So I went all in on church. I cut out all my relationships with friends who were not on the same page as me and I spent all my time going to church services. I tried to recreate in my room, in my private life, that same emotional euphoria that my parents felt as young people and that I had felt at times. That became my entire world.

Martin: So when you were in this particular chapter and you were really committing your life to the church and your identity as a Christian, how did that jive with the rest of your life? What was it like in your professional life, your dating life?

Ward: Well, you've opened up a whole can of worms by asking that.

Martin: Let's open it up!

Ward: It's important to explain that the theology we were embracing at that time was focused on our own basic badness. And we would call it indwelling sin or original sin, but it led to a very intense focus on what I was doing wrong and a suspicion of my motives in all cases. A lot of us young men, with the encouragement of some of the pastors, were having these meetings where we would talk about how often we had looked at pornography and even greater detail about our sins on the internet. It was not a happy time, Rachel.

Martin: You had to share all this in a group, right?

Ward: Correct. Sometimes in somebody's kitchen, sometimes at a Starbucks. I remember trying to pull my chair as close as possible to the person next to me so that we could talk as quietly as possible. I was just sitting there thinking, "Why are we doing this in Starbucks again?" I might have wondered why we were doing it all but when you're caught up in something it's hard to pump the brakes.

Martin: But it wasn't just the fear of public embarrassment. In the book you describe a self-loathing that came over you when it came to sex or any kind of sexual thought.

Ward: Yeah, the vigor which we were encouraged to root out the impurity inside us led to a huge sense of shame anytime I fell short. We would talk about passages of scripture where it talks about how if you look at a woman lustfully you've committed adultery. And we would take that and say, "How much worse is it if you are looking at porn? Basically it's the same as if you had committed adultery." So there's obviously philosophical problems with interpreting that passage too literally, but that's the way we interpreted it. And so you walk around feeling really, really bad about yourself and then you try to work your way back to a place of atonement for your sins. Obviously the teaching is that Christ would have atoned for it but you can't help but try to atone for it yourself.

Martin: In 2012, the pastor of your family's church was accused of covering up crimes of child sex abuse. [NOTE: One church member was found guilty, but church leaders deny any cover up and were never charged.] Besides the hideous nature of that crime, what did that revelation uncover for you about how some evangelical congregations operate?

Ward: If you are continually operating in a world where you believe God is speaking to you, and as a leader speaking to you in a particular way, and that you have answers about ultimate reality and right and wrong that other people don't have, I think it actually predisposes you to think that you know better than law enforcement or anyone who's not in your world and doesn't think like you. I think a lot of that cover up was them saying, "We're going to handle things internally according to the way we think is best and that's the right thing to do." And they might still think that.

Martin: But by this point you had already broken with the church?

Ward: Yeah.

Martin: Can you tell me what precipitated that? What in the end made you decide that you needed to find your own spiritual path?

Ward: That's a good way of putting it. By the time the sex abuse cases issue came to a head in 2012 I had been out of that church for about a decade. I had become exhausted from that cycle of failure and atonement that I described earlier. I also felt a sense of suffocation from being in an environment where everyone thought the same thing and sang in the same chord structure. I've always felt like it was a good thing to be around people who thought differently than I did, who could challenge my thinking. And as a result of working on this book I've come to believe that journalism saved me from fundamentalism.

Martin: Can you say more about that? How?

Ward: It's taught me that truth is not a set of answers that you begin with and then retroactively fit the questions to. It's something that requires rigor and modesty and a lot of work. And also our recognition that a lot of things that we would like to put in boxes labeled true and false defy our ability to do that.

I think fundamentalism is this desire to put answers out of reach of questioning. I think one of the icebreaking statements for me has been a very simple one, it's just: "I could be wrong." I've embraced that over the years and it's been so liberating in many ways.

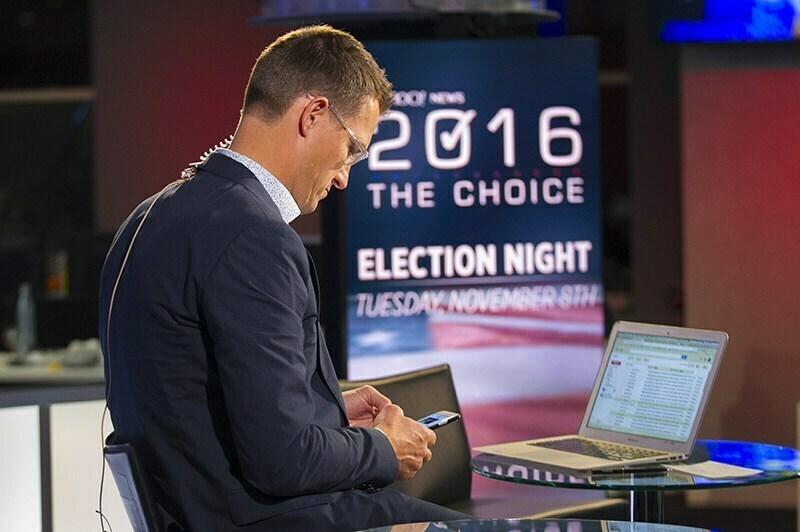

Martin: That idea of certainty, that sort of opens the door to my next question. When Donal Trump came along and white evangelicals painted him as some kind of savior, it was completely confounding to most people in the media and Americans who didn't have a connection to the evangelical church. But this did not shock you. Can you explain why this bizarre marriage between Donald Trump and white evangelicals made sense to you as someone from that world?

Ward: I don't know that it did make a ton of sense to be honest. I guess I've come to understand it in retrospect and there are still parts I don't get. There were some evangelicals who painted Trump as God's man, but a lot of evangelicals I knew personally and some public figures were the type that were repulsed by Trump and then came to a place of either trying to ignore politics or in the case of my own family, rationalized their way to embracing him. And then once you get into the general election timeframe of 2016 and beyond I think tribal political identities overtook religious identities. And Trump was very good at provoking outrage, which further solidified his supporter's attachment to him. But there was a process of resignation, then rationalization and then once it was Republican versus Democrat the political identities snapped into place.

Martin: How's your faith now?

Ward: I still affirm a lot of the same core teachings of Christianity that a lot of evangelicals do, but I hold it with a more open hand and a sense of epistemic modesty. The sense of being aware of how much we don't know and embracing the sense that I could be wrong has given me a more open-handed stance towards faith. I just love the idea that if I say we know it then I've eliminated the need for faith. That to me has become such an exciting thing about faith. I actually don't know if this is true or real and so I'm on a quest to continue onward and upward, as my dad likes to quote C.S. Lewis, in a reliance on that faith.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.