Section Branding

Header Content

What recession? Why stocks are surging despite warnings of doom and gloom

Primary Content

It has been a hell of a year so far. Three regional banks collapsed, the United States came close to defaulting on its debt for the first time in its history, and the Federal Reserve continued to hike interest rates aggressively.

But despite all that, the stock market surged in the first half of the year. What gives?

A lot has to do with the economy.

Despite widespread expectations that the U.S. could be headed for a recession this year, the economy has proved a lot sturdier than many on Wall Street had forecast.

There are other reasons too. Artificial intelligence has helped lift the technology sector, for example.

All that combined has meant the three major indexes have ended the first six months of the year in a bull market, meaning they've surged more than 20% from their most recent lows.

But it's not all as rosy as the numbers seem to show — and there's a lot of uncertainty about the path ahead.

Here's a look at how markets stand and what could be in store for the rest of the year.

Why stock markets gained so much

There has been a remarkable change in sentiment from the start of the year.

In January, economists and policymakers were warning about a potential downturn, and that made investors extremely conservative, according to Savita Subramanian, the head of U.S. equity and quantitative strategy at Bank of America.

"We've spent basically a year now worrying about this recession and then worrying about all these potential calendar events, like the debt ceiling," she says. "And in that period of time, investors have grown increasingly cautious."

They shied away from risky bets and steered clear of cyclical stocks — companies whose performance tends be correlated to economic booms and busts.

But the economy has confounded many forecasters by proving to be sturdier than expected — and that has helped markets weather tough events like the turmoil that enveloped the banking sector with the collapse of lenders such as Silicon Valley Bank.

What has made the economy so resilient? There are a number of factors. The labor market has remained strong, despite some high-profile layoffs. The construction sector has hummed along, while other companies in areas like retail have been reluctant to shed workers for fear that they won't be able to hire them back.

And consumers have continued to spend despite high inflation, splurging on things such as travel and eating out, while cutting down on other expenses.

It's not only the U.S. economy, but other countries have done better than expected as well, helped in part by lower energy prices and the easing of pandemic restrictions in China.

"Perhaps the biggest surprise over the last six months is that we actually saw a pretty strong recovery in global growth," says Paul Mielczarski, the head of global macro strategy at Brandywine Global Investment Management, a boutique investment firm.

But it's not all rosy

Despite the strong market gains, there's one troubling detail: The stock market's gains have not been broad-based.

That's usually a sign that gives Wall Street pause.

In fact, a lot of the recent rally in markets can be attributed to the excitement around artificial intelligence after the debut of ChatGPT.

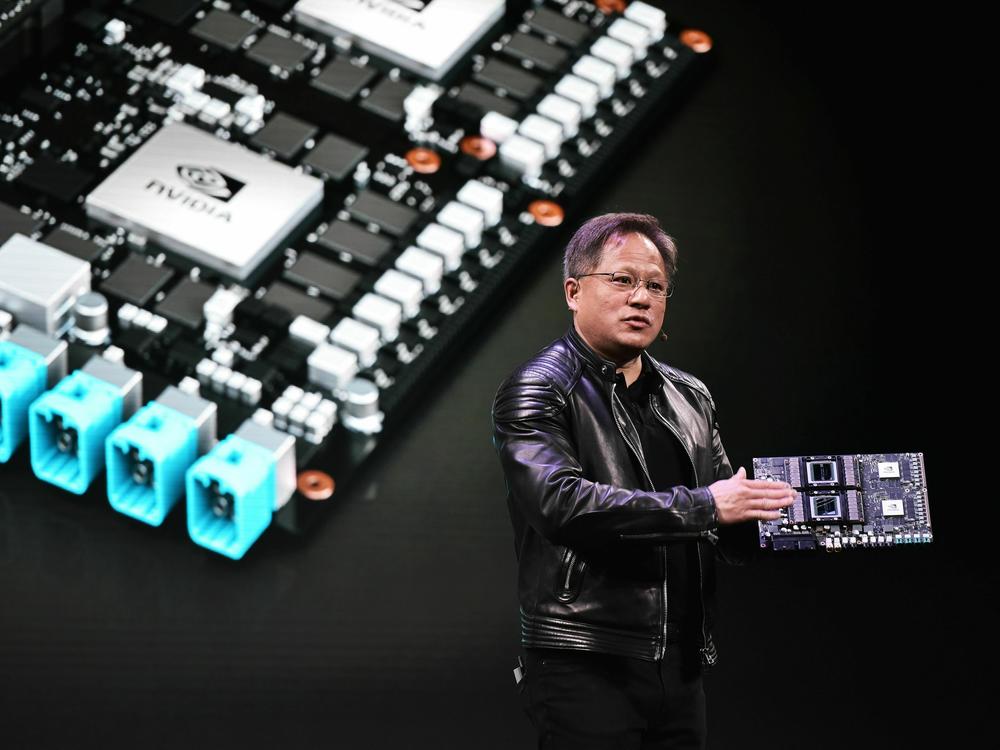

That has led to a surge in shares of companies with businesses tied to AI, including chipmakers Nvidia, AMD and Qualcomm.

But as the dot-com bust in the early 2000s showed, it can make the broader market vulnerable if that excitement for AI suddenly reverses.

This week, after The Wall Street Journal reported that the Biden administration is considering new restrictions on the export to China of chips used for AI, shares of those companies suffered.

For investors to become more confident, the gains seen in AI will need to spread to other kinds of companies, which would be more reflective of broader optimism about the overall market's prospects.

Bank of America's Subramanian is optimistic that this could start to happen in the second half of this year.

"We could see big gains in the broader market outside of those bigger tech names," says Subramanian.

Subramanian attributes her optimism to hope that any recession may prove to be relatively mild, which could boost the prospects of other sectors that have not gained as much as tech.

But there are still lingering worries about banks

At the year's midpoint, there are also worries the banking turmoil will resurface.

After the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank, many of the customers of smaller regional banks moved their money to larger institutions.

A lot of these lenders also lost deposits — which are, of course, key to a bank's business — to higher-yielding investments, such as money market funds.

Recently, those outflows from the smaller lenders have stabilized. But analysts are vigilantly watching for signs of more distress, and Wall Street will get a better sense of how these banks are doing when lenders report their latest earnings starting this month.

They're also paying attention to another consequence of that collapse.

Credit conditions have tightened since then, which means banks are becoming more conservative about making loans to consumers and businesses.

If that continues, it could have an impact on economic growth.

Moreover, banks are still vulnerable to high interest rates because they can erode the value of the vast bond portfolios that many lenders have.

And other challenges are ahead

Despite the gains, some of the big trends in the economy haven't necessarily changed.

Inflation has eased but remains stubbornly high, and the Federal Reserve has signaled clearly that it will need to continue raising interest rates. That means borrowing costs across the economy will continue to rise, so mortgages and loans will continue to get more expensive.

It takes a while for higher rates to filter through the economy, so even as recession fears have subsided somewhat, they have not gone away completely.

"We're still going through the most aggressive monetary tightening cycle since the early 1980s," says Brandywine Global's Mielczarski. "And I think we're only really going to see the full impact of that tightening cycle over the next 12 to 18 months."

Therefore, the economy may very well avert a recession this year, but there's still the chance of a downturn in 2024, which would mean a lot of the gains in stocks could still reverse.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.