Caption

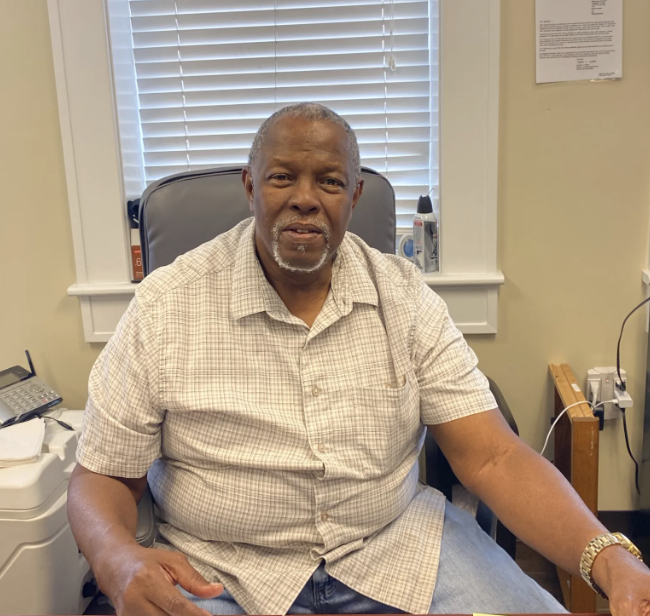

At 73, Jerome Irwin Sr. remembers the funeral parlor being around since he was a child.

Credit: Caelen McQuilkin/The Current

By Caelen McQuilkin, The Current

Editor’s note: This article was updated June 28 to include updates from the Historic Preservation Commission debate and vote.

Some people call them “legitimate and distinguished components” of Savannah’s architectural history. Others see them as an “urban planning blunder, a missing tooth on the face of Forsyth Park.” Still others view one of the structures in question as an important site of Black history in Savannah.

The Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) considered these clashing views about five buildings that hug the southwest corner of Forsyth Park and decided to deny a request to demolish three of them.

The demolitions, requested by Greenline Architecture on behalf of an ownership group that includes David Paddison, Reed Dulany III, and Brad Baugh, are necessary to fulfill the owners’ plan to replace the structures at 1001 and 1015 Whitaker St., 120 and 124 W. Park Ave., and 115 W. Waldburg St. with an office complex and underground parking garage. The firm has yet to disclose its full design.

The HPC decision followed recommendations from its own staff reports that three of the buildings — those at 1001 and 1015 Whitaker St. and 124 W. Park Ave — should be preserved and not torn down because they have “contributing status.” That designation, opposed by the owners, means that the structures should be protected from demolition or relocation because of their historical value.

Debate over what qualifies these buildings for such status is just the latest chapter in a long-running controversy over development and preservation in Savannah.

Some argue that certain sections of the city should be home to only some architectural styles. Others believe that the debate is really about gentrification, as well as the city ignoring Black history when it comes to deciding what structures should be protected. In this instance, they cite the endangered Campbell & Sons Funeral Home, the brick funeral parlor at 124 W. Park Ave., which has served Savannah’s Black families for generations.

The property owners say their plans for the four square blocks that encompass the five buildings will benefit downtown Savannah by providing high-end office space and much-needed parking for those who use Forsyth Park, one of the city’s crown jewels.

Paddison, the president of Sterling Seacrest Pritchard, says that the planned office building on his and the adjacent properties promises to revive a section of downtown that has been underdeveloped for decades. The increased density of office workers and parking places will help revive small local businesses that have closed. (Editor’s note: Paddison is a member of The Current’s board of directors.)

“Underdevelopment has a negative effect for everyone. It creates food deserts and holes in the community,” Paddison said. “There are under-utilized opportunities for everyone.”

It’s unclear how much input residents in west Savannah — especially those who have watched swathes of historic Black Savannah wither away — have in the decision-making over the proposed complex, and what weight, if any, that input has.

“It may not have historical significance to them. But to us, to the Black community, it has historical significance,” said Jerome Irwin Sr., president of the Savannah chapter of the Phillip Randolph Institute.

At 73, Jerome Irwin Sr. remembers the funeral parlor being around since he was a child.

Now that the HPC has voted to deny the demolitions, the owners can appeal to the Zoning Board of Appeals, whose seven mayor-appointed members will ultimately decide on the demolition request.

The broader conversation surrounding the project, though, will not be resolved by a vote, because the debate is not just about historical preservation. It’s also about the different ways that Savannahians envision the city and its future.

Before the HPC can issue a demolition permit, it’s required to evaluate the historic value of each building. For the five properties adjacent to Forsyth, its assessments come to different conclusions.

HPC staff reports say that the buildings on 115 W. Waldburg St. and 120 W. Park Ave. do not qualify for “contributing status,” and the staff recommends approval for destruction, with the provision that the structures’ materials be preserved.

However, the commission cites the “exceptional importance criteria” for the buildings where they recommend denial for demolition — the funeral parlor, and 1000 and 1015 Whitaker St. — claiming that these buildings do qualify for “contributing status.”

The definition of “exceptional importance” refers to structures built outside of 1870-1923. This time frame is one requirement for “contributing status” under the typical guidelines in the city’s historic districts.

Buildings of exceptional importance may be constructed more recently than 1923, but still must “possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association.” They also must meet one of the usual qualifications for “contributing status” — association with people, events, or architectural styles important to “the broad patterns of our history.”

Savannah residents and business owners have divergent views on what “historical contribution” means, and whether the buildings off Forsyth proposed for demolition qualify for the designation.

The focus of those questions is the Campbell & Sons Funeral Home, which rents its space on 124 West Park Avenue. Formerly known as the Sidney A. Jones Funeral Home, the funeral parlor has served west Savannah Black families for 87 years.

“[It] served my family for generation down to generation. My grandmother, my great-grandmother, my great-great grandmother and grandfather all were buried by Sidney A. Jones,” said Kim Hatccher, a Savannah resident and bus driver for the Savannah-Chatham County public school system.

For the Reverend Alan Mainor, president of the Racial Justice Network in Savannah, the debate about historic preservation should take into account the massive gentrification this part of the city has endured. He walks through the streets of this area, once known as Savannah’s Black business district, and sees what is no longer there.

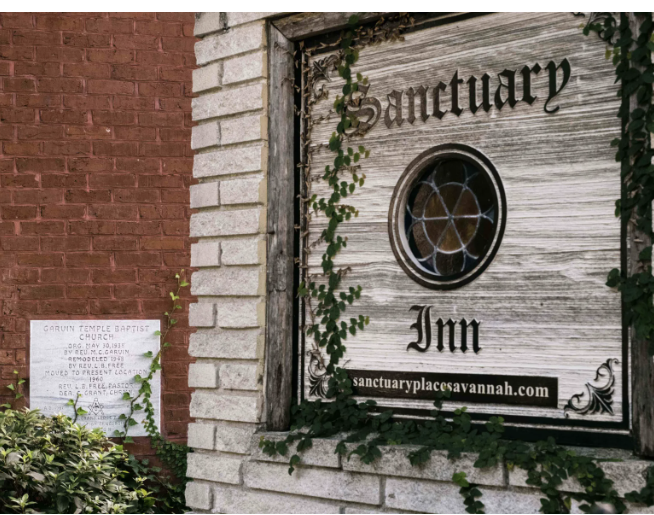

A plaque commemorating the Garvin Temple Baptist Church, a historical Black church, is still visible behind the sign for the Sanctuary Inn.

“That was a convenience store,” said Mainor, pointing to a corner in the same neighborhood where the funeral parlor and 1000 and 1015 Whitaker St. stand today. “That was a laundromat.” Pointing to the deconsecrated church on W. Duffy St. that has been converted into a boutique hotel, he says, “this was a historical Black church.”

Connections like these are historically valuable, as is the legacy of the funeral parlor. “Gentrification is real in this community, and we can’t afford to take [the funeral home] out,” Mainor said.

Lee Andrews, a Black resident of Savannah, noted the funeral home as one of the last Black-owned businesses in the area.

“That’s the last thing we have … that’s the last. You’re gonna take that away?” he said. “I don’t see how that could happen … it’s been there forever. Sidney Jones is part of Savannah, Georgia.”

The sense of loss is heavy, said Essie Roberts, who also lives in Savannah.

“It means a lot to me as a Black person,” she said. “So much has been taken from us. And we’re tired of them just taking, taking, taking. That’s our funeral home.”

Campbell & Sons did not respond to requests for comment.

A 2023 photograph depicts the properties' shifts from their positions on 1888 and 1955 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps.

The owners, meanwhile, are looking towards the future, at the architectural makeup of the neighborhood.

In a letter to the historic preservation committee, the architects cite the city’s own designation of these properties as “non-contributing,” a status that has remained the same for some four decades.

The architects say conservationists should prioritize architectural relevance rather than the potential that a building could have historical value.

Their letter does not specifically cite the Campbell & Sons Funeral Home. The funeral parlor is a 19th-century building, and 1001 and 1005 Whitaker St. are 20th-century buildings constructed in mid-century modern style architecture. The report doesn’t dispute their age. Rather, it raises questions about the location of this architectural style in downtown Savannah’s larger scheme.

New development in place of these buildings will resolve the incohesive layout of the block but also create much-needed space for parking and offices.

A photo taken of the building that sat at 115 West Waldburg Street sometime in the 1970s-80s. Two Victorian homes similar to the one above were taken down to build the mid-century modern style building that property owner David Paddison wants to demolish there now.

The Victorian Neighborhood Association (VNA), an association of businesses and residents in the district, hasn’t issued an opinion about the proposed development because the actual plans have not been made public. But for now, the neighborhood association does not oppose demolition.

In two neighborhood surveys conducted in 2019 and 2022, members of the VNA evaluated buildings in their area and shared their opinions on granting historical protections to additional ones. In both surveys, the majority of VNA members said the buildings Greenline has requested for demolition disrupt the neighborhood’s architectural style.

In the 2022 survey, 13 out of 17 respondents voted that both 1001 Whitaker St. and 1015 Whitaker St. should not be considered “contributing” structures. Eleven out of 17 respondents said that the funeral parlor should not be considered “contributing.”

In the 2019 survey, which brought in 40 total responses, the comment section for 1001 and 1015 Whitaker contained “critiques of those buildings as being very low-rise, low-density, suburban in their disposition, surrounded by surface parking, unable to create a welcoming streetscape that frames Whitaker and Forsythe Park,” said Ryan Madson, then-president of the VNA.

According to Madson, the VNA’s 2022 re-survey came in response to a staff-initiated petition from the HPC, which aimed to designate ten buildings within the Victorian District — including 1001 and 1015 Whitaker St. and the funeral parlor — as “contributing” buildings.

At the time, the HPC remarked that these buildings are “valuable early and mid-century architecture that, if demolished, would be difficult to replicate.”

The HPC’s petition to add these buildings to the Contributing Resources Map, however, was withdrawn by city manager Joseph A. Melder before it was finished. According to Madson, the city manager made this decision after receiving the VNA’s opinion and survey about the buildings. The city manager went on to ask the city to “complete the survey so it’s more holistic, so it’s not … cherry picking certain buildings,” Madson said.

“Protecting these [mid-century modern] buildings would be a grave mistake,” reads a letter the VNA submitted for the HPC’s March 31, 2022, meeting. It continued:

“Imagine their appearance in fifty or one-hundred years, in advanced stages of disrepair following decades of expensive and superficial maintenance. As their present condition of decomposition suggests, these buildings and their low-grade materials will become further unglued, delaminated, and rotten beyond hope of repair. These are not the timeless icons of Modernism.”

This opinion, too, raised controversy. Daves Rossell, SCAD professor of architectural history, member of the Georgia National Register Review Board, and past chair of the Chatham County Historic Preservation Commission, wrote in an email to The Current.

“To demolish them would lessen the diversity of our built environment in terms of expression, function, and age — all important components of a truly significant and just plainly ‘true’ urban form,” he said.

When it comes to the preservation of Black history, however, the architectural experts have paid less attention.

The HPC staff report for the demolition request touches on the resonance of Campbell & Sons, noting that “it is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history, specifically, African American history in Savannah.” While the report doesn’t elaborate further, commissioners discussed at more length during the June 28th meeting. One commissioner said that the funeral home had already been relocated to Park Avenue due to urban renewal, and that “in a sense, this is kind of repeating history.” Keith Howington, Senior Project Manager at Greenline Architecture, commented that the matter is only about whether the building itself is “contributing” or not. “They don’t own the building, they own the business,” he said.

For some residents living in the vicinity of the proposed demolition, a new building project raises completely different concerns: noise and traffic.

“[The] excavation of an underground parking garage … the magnitude of a project like that does not belong in the middle of a neighborhood,” said Clara Greig, a neighborhood resident. She fears that the parking garage will bring “additional traffic, additional noise, additional air pollution,” to the neighborhood.

Amid the debate of the technical merits of architectural styles, Mainor hopes the HPC and developers keep one thought in mind: preservation should not be a force for gentrification.

“If you get rid of this place,” he said of the Campbell & Sons funeral home, “Where will we go?”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.