Section Branding

Header Content

Parts of a Munich synagogue demolished by Nazis are found in a river 85 years later

Primary Content

After Adolf Hitler ordered Munich's main synagogue to be demolished in June 1938, no one knew what became of the rubble — until last week. Construction crews working on a river dam unearthed some 150 tons of stone columns and a tablet bearing the Ten Commandments in Hebrew.

Bernhard Purin, the director of the Jewish Museum Munich, says they were found 7 or 8 miles away from the synagogue site, which was converted into a parking lot and now houses a department store and a monument to the original building.

The workers contacted German heritage protection authorities and then Purin, an expert on synagogues who said it quickly became clear to him where the rubble had come from.

"[That was a] day which is very unusual in my professional career, because we don't usually find a synagogue in a river," he told NPR in a Zoom interview.

Purin said it was "especially touching" to see the Ten Commandments tablet, a symbolic object that would have played a central role in synagogue services as "all worshippers look to it."

Now the heavy stones will be carefully transported to another site for further examination, research that he says could take up to two years. He has also been told that there could be more stones in other parts of the river, but that will become clear only as the dam renovation progresses in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, he says, experts will be looking to figure out which parts of the synagogue have been preserved (using photos of the original site) and what they might be able to do with them — like whether there are enough stones to re-create its eastern wall, for example.

Munich Mayor Dieter Reiter described the discovery as a "stroke of luck," the BBC reported, citing local media. His team said it's the city's duty to protect and return the findings to the Jewish community.

Ultimately, Purin would like to see the ruins used to honor Jewish life in Munich before the Holocaust, in which 6 million European Jews were murdered. Today, the city is home to about 9,000 Jewish people, he says, out of some 1.5 million residents.

"I think that's the most important," Purin says. "That it becomes something like a monument, both for the Jewish culture in Munich and the destroying of it."

Hitler deemed the landmark an eyesore

The synagogue was one of the first in Germany to be torn down during Hitler's rule, authorities say. It had been a center of Jewish life and a major Munich landmark.

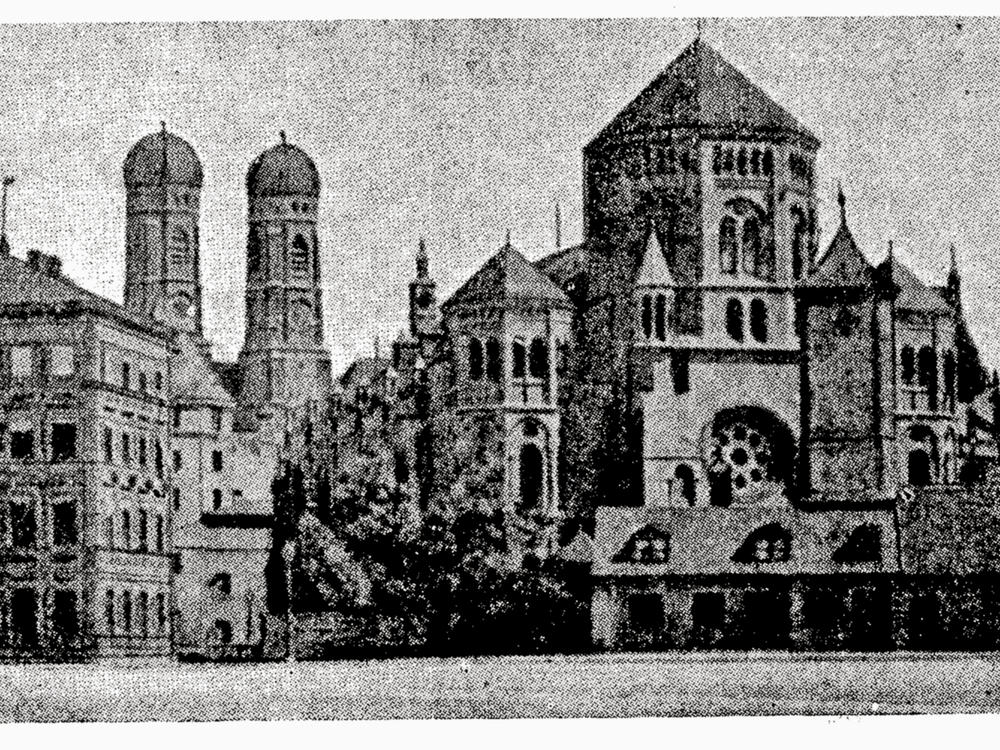

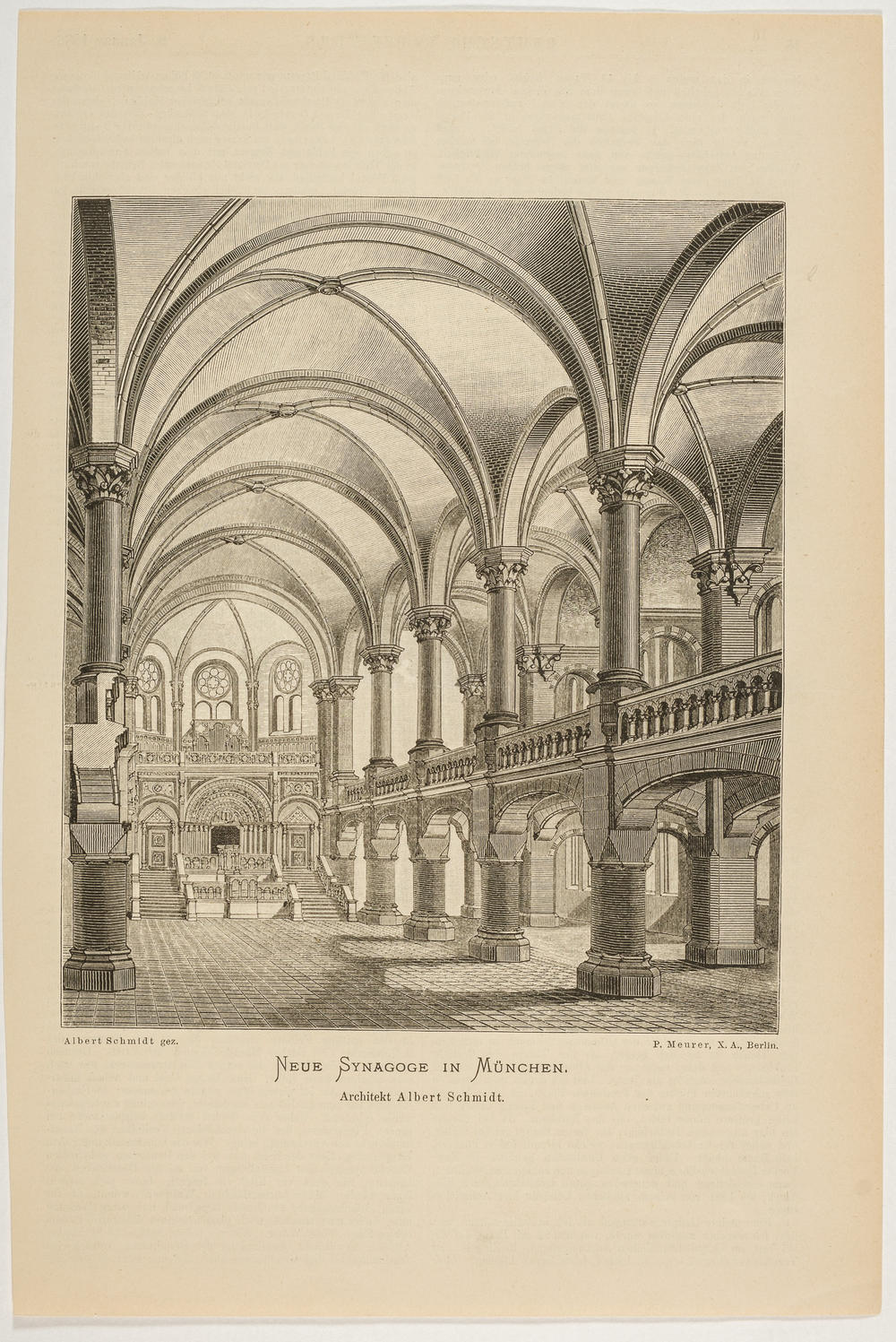

The massive building was designed by prominent German architect Albert Schmidt and opened in 1887. It had more than 1,500 seats and served as the city's main synagogue, Purin says.

And it had been in use for barely a half-century when Hitler ordered its demolition in June 1938 — months before Kristallnacht (or the November Pogrom) wrought the destruction of hundreds of synagogues across the country.

Purin says two main reasons explain why this particular synagogue was one of just a small handful razed so early.

For one, the Nazi party, which was founded and headquartered in Munich, simply didn't want such a huge synagogue there.

"The synagogue was very close to a main art gallery with a restaurant where Hitler liked to have dinner when he was in Munich," Purin says. "And ... he had to look out at the synagogue, [which] he disliked."

Hitler deemed the structure an eyesore and personally ordered its removal, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported at the time.

It also served as a "test" for Kristallnacht, to see how the German public would react to the destruction of a synagogue, according to Purin. There was no reaction, he said.

The Nazi movement was also targeting Catholic and Protestant churches, he added, and Hitler had ordered the demolition of a Protestant church around the same time, which prompted considerable backlash.

"And so they saw it's quite difficult to start demolishing churches, but no problem with demolishing synagogues," he said.

The building's components were razed and reused

The congregation's rabbi was given a few hours' notice about the demolition, and hundreds of community members worked through the night to remove Torah scrolls and other property from the building, the JTA reported at the time. They passed on their newly acquired organ to a Catholic church.

The municipality reimbursed the Jewish community for only about one-seventh of the value of the synagogue and neighboring Jewish community building, according to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Israel.

The building was demolished in June 1938 by the Leonhard Moll building company, and the site became a parking lot.

"We never knew what happened to the stones of the synagogue after demolishing: where they were stored, for what reason they were used or whatever," Purin said.

We now know, he says, that the company stored at least some of the stones — as well as other stones and bricks from bombed houses — at some other site for at least two decades.

And in 1956, it used some of those stones to build a barrier in the river, though that wasn't known at the time.

After World War II ended, Purin says, it wasn't unusual for new buildings to be built using materials from others that had been destroyed. His own house, he says, dates back to the 1950s and is a "disaster" to repair because of its mixture of stones and bricks.

He says it's theoretically possible that pieces of the synagogue were used to rebuild all sorts of structures around the city.

"It could be that in other houses in Munich, there's also other parts of the synagogue," he says.

As the work of recovering and identifying the rubble continues, Purin says his dream is that more parts of the Torah ark — an ornamental cabinet that houses the holy scrolls — will be found.

But even the pieces that have resurfaced so far are making history.

Charlotte Knobloch, the president of the Jewish Community of Munich and Upper Bavaria, told the German newspaper Münchner Merkur that they show how much deeper the city's Jewish roots run than the end of World War II.

"I really didn't expect fragments of the old main synagogue to survive, let alone see them," said Knobloch, who was born in 1932 and remembers visiting the synagogue as a child. "It's all still very unreal."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.