Section Branding

Header Content

They marched for desegregation — then they disappeared for 45 days

Primary Content

In the early 1960s, civil rights protests were picking up speed across the country. Sometimes, protest marches included children as young as 12 years old.

Usually, children who were arrested at protests were bailed out by activist groups, or eventually released to their parents. But on July 19, 1963, during a march to desegregate a theater in Americus, Ga., a group of Black girls was arrested — and for the rest of the summer, their parents had no idea where they were.

One of those girls was Lulu Westbrook-Griffin.

"We were gung-ho young people who want to change the system," Westbrook-Griffin told Radio Diaries.

Westbrook-Griffin was 12 years old at the time. Her older brother, nineteen-year-old James Westbrook, was a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. With SNCC, Westbrook organized a march to desegregate the Martin Theatre, the only theater in Americus.

At least 40 people attended. But as the marchers approached the theater, local police demanded that they disperse, and began beating them with clubs and setting dogs on them.

"Some of us were taken by our feet and arms and thrown in a paddy wagon, and I was one of them," Westbrook-Griffin recalled.

Westbroook-Griffin's brother escaped arrest. "I told Mom that night: 'They drove her off in a paddy wagon and I have no idea where they went,'" James Westbrook said.

Along with at least 13 other girls, Westbrook-Griffin was transported to a single cell of the Leesburg Stockade — an abandoned, Civil-War-era building more than 20 miles away from Americus.

For the next 45 days, the girls would be subject to squalid living conditions. The stockade lacked running water, plumbing and beds. As the weeks passed, conditions only deteriorated.

"We were putting our waste in the shower drain because the toilet was overflowing," Westbrook-Griffin recalled.

Back in Americus, SNCC activists and parents were focused on locating the missing girls.

"Americus is a small town where everybody knew everybody," James Westbrook said. "It was a network of parents trying to find out, day by day, where their children were."

Throughout July and August, SNCC activists went from jail to jail in search of the missing girls. At one of SNCC's mass meetings, someone mentioned a rumor that the girls were being held in the old Leesburg Stockade.

Danny Lyon was a photographer for SNCC at the time. "James Foreman, who was executive secretary, said to go down and check it out," Lyon told Radio Diaries.

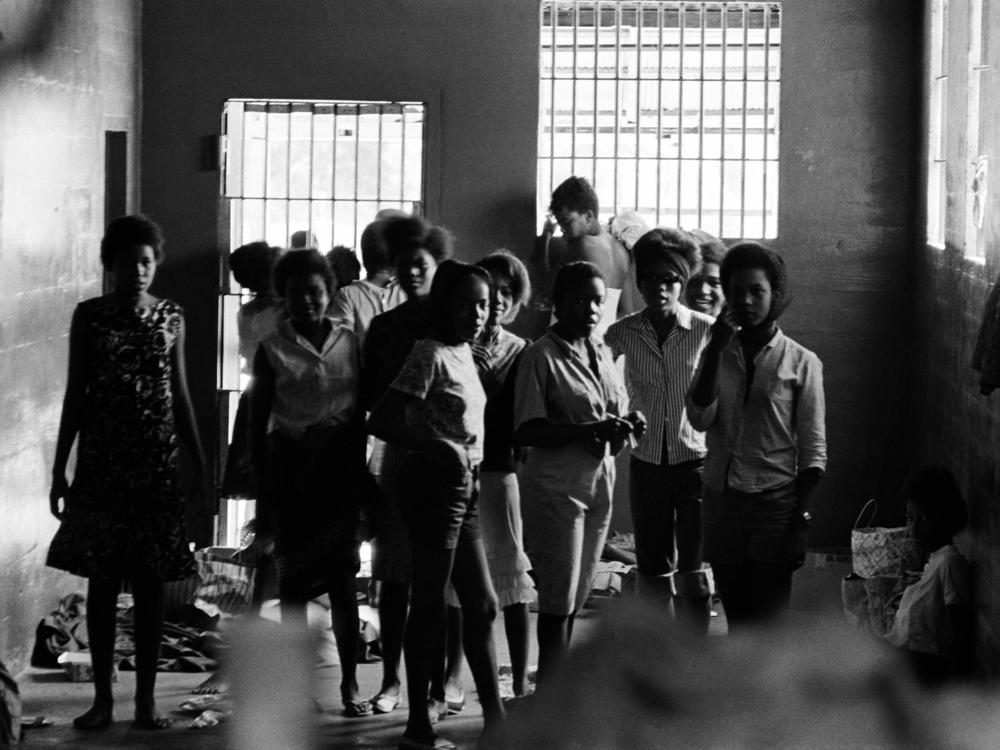

Lyon drove to the Leesburg Stockade after dark. There, he took clandestine pictures of the girls and their living conditions through bars of the building.

Lyon's photos confirmed the girls' location to parents and activists, providing leverage as they fought with authorities for the girls' return. Finally, on Sept. 1 – 45 days after they were taken – the police released the girls to their parents. Danny Lyon's photos appeared in Jet magazine in late September and in a special issue of SNCC's The Student Voice newspaper in 1964.

Westbrook-Griffin and the other girls were never formally charged after the march. They also weren't given a reason for why they were held in the stockade so long.

"Was it to break me? Was it to make me fearful? Was it to teach me a lesson?" Westbrook-Griffin says. She wonders to this day why the girls were kidnapped. "But when you look back at it now, you realize it pretty much was a badge of honor rather than a badge of disgrace. We were part of something that matters."

Lulu Westbook-Griffin and the other girls in the Leesburg Stockade were never formally charged. And local law enforcement never explained why they were held in the stockade for so long.

The stockade is still standing. In 2019, the state of Georgia put a historical marker on the site, acknowledging the incident. It reads, "Because their families were not initially told their location and the girls never faced formal charges, they became known as the Leesburg Stockade Stolen Girls."

This story was produced by Mycah Hazel of Radio Diaries. It was edited by Joe Richman, Deborah George and Ben Shapiro. You can find a longer version of this story, and other stories like it, on the Radio Diaries Podcast.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.