Section Branding

Header Content

The settlers brought the lottery to America. It's had a long, uneven history

Primary Content

One very lucky person in Florida just won $1.58 billion in the Mega Millions jackpot drawing, with an estimated before-taxes payout of $783.3 million.

The Mega Millions started in 1996 as the Big Game. It is now played in 45 states, the District of Colombia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Its cousin, Powerball, debuted in 1988 as Lotto America, and is offered today in the same states as Mega Millions, but not Puerto Rico. Only Alabama, Alaska, Hawaii, Nevada and Utah do not sell lottery tickets.

In short, state lotteries are thriving, with Americans spending an estimated $100 billion each year on tickets. But that wasn't always the case. Their history, both as public and private games, has had a long and sometimes rocky history in the U.S.

Here are three things to know about them.

America's earliest settlers brought the lotto with them

In 1612, the Virginia Company of London was authorized by King James I to run a lottery to help finance ships to the Jamestown colony in Virginia.

Despite Puritans viewing gambling as "a dishonor to God" and "a door and a window" to worse sins, "By the 1670s, gambling was a well-established feature—and irritant—of New England life," according to the Colonial Williamsburg website.

Lotteries flourished in the American colonies in the mid-to-late 1700s and their proceeds went to build roads, bridges, churches and colleges, says Victor Matheson, a professor of economics at the College of the Holy Cross and a lottery expert. "We've had lotteries in the United States for a super long time and a lot of big things in U.S. history were actually financed by them."

The founding fathers were big into lotteries too. In 1748, Benjamin Franklin organized a lottery in Philadelphia to help fund the establishment of "a militia for defense against marauding attacks by the French," according to the Library Company of Philadelphia, an independent research library.

Matheson says John Hancock ran a lottery to help build Boston's Faneuil Hall and in 1767, George Washington ran one to build a road in Virginia over a mountain pass. The so-called Mountain Road Lottery failed to earn enough to make the project viable.

Thomas Jefferson said of lotteries "they are indispensable to the existence of man, and every one has a natural right to pursue such one of them as he thinks most likely to furnish him subsistence."

Around 1800, Denmark Vesey, an enslaved person in Charleston, S.C., won a local lottery and used the money to buy his freedom. Vesey was eventually executed for his role in planning a failed slave revolt in 1822.

They disappeared by the late 1800s

The same religious and moral sensibilities that eventually led to prohibition also started to turn the tide against gambling of all forms beginning in the 1800s, says Matheson.

Corruption also worked against lotteries during this time period, he says. Lottery organizers could simply sell tickets and abscond with the proceeds without awarding prizes.

"It's partially a religious and social distaste, but it's also a little bit of public policy and public welfare protection to get rid of lotteries that were corrupt," Matheson says.

The Louisiana Lottery Company, a private enterprise started in 1868 by a group of entrepreneurs, sold tickets well beyond the state borders, with only about 7% of the company's revenue coming from Louisiana, according to Lousianalottery.com.

In 1890, however, Congress banned the interstate promotion and sale of lottery tickets. That forced the Louisiana company to shut down "[a]mid state and national charges of corruption," the website says. "It then moved to Honduras after the federal government passed laws banning the sale of lottery tickets through the mail. By 1894, legal lotteries were no longer held in the U.S."

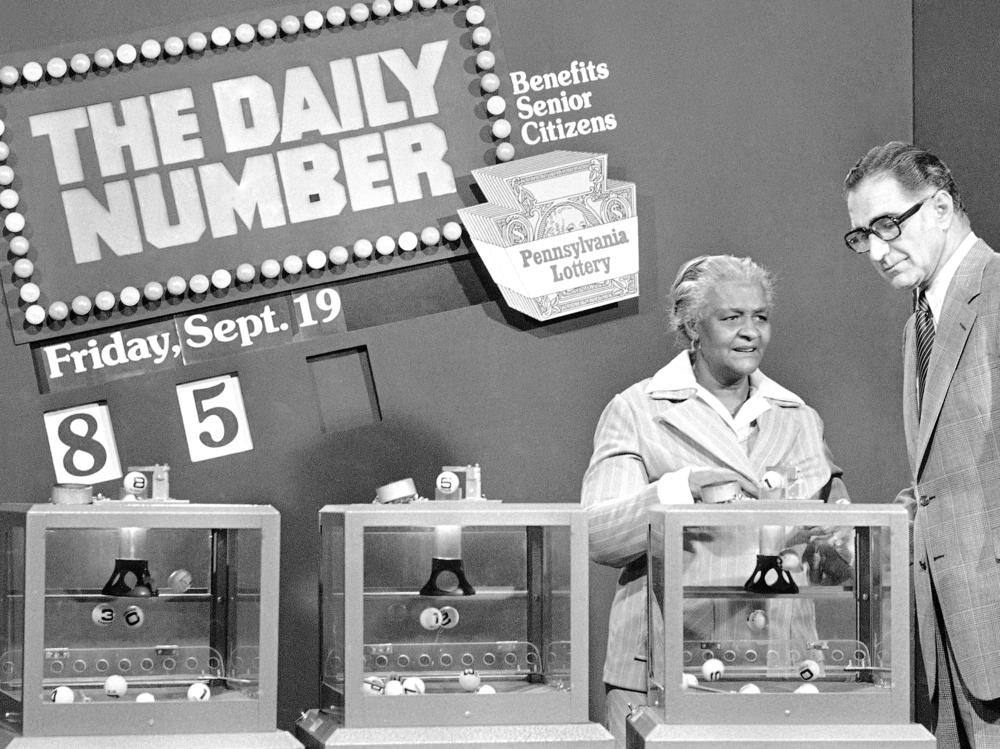

State lotteries made a comeback starting in the 1960s

The post-World War II prosperity enjoyed by the U.S. allowed states to offer an "increased array of state services without raising taxes," Jonathan Cohen, author of For a Dollar and a Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America, told WBUR's On Point in January.

"It really starts grinding to a halt in the 1960s with inflation, with increased spending on the Vietnam War" creating budgetary shortfalls, he says. Still, voters "want all the services they've gotten used to, but also don't want higher taxes."

The lotto comeback started in 1964 with New Hampshire, one of only three states at the time without a sales or income tax, notes Cohen.

That made it "really heavily reliant on property taxes, and willing to take a chance," he says. New Hampshire tried to create "legitimacy" for lotteries despite fears at the time that "the games are gonna be corrupt and infiltrated by organized crime."

By the 1980s, an avalanche of states followed suit and started getting into the lottery game.

"As soon as one state legalizes, it is very common for bordering states to legalize pretty quickly as well," says Matheson.

"The lottery clearly spreads in a geographical pattern as the state adopts a lottery within several years, states around it seem to adopt that. And so we saw lotteries kind of spread across the United States that way," he says.

Multi-state lotteries, such as Powerball and Mega Millions, came into being starting in the mid-1980s, as smaller states banded together to increase the size of jackpots, and attract more players.

The last state to approve a lottery was Mississippi, in 2019.

The odds today may be in favor of lotteries, but for anyone buying a ticket, they've gotten steadily worse as the size of jackpots and the number of players has increased. For Mega Millions, the chances of winning are about 1 in 302.6 million.

Good luck.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.