Section Branding

Header Content

A look at the tumultuous life of 'Persepolis' as it turns 20

Primary Content

The English translation of the now classic memoir Persepolis by comics artist, painter and filmmaker Marjane Satrapi turned 20 this year — and it's being celebrated with the release of a new hardcover edition in August.

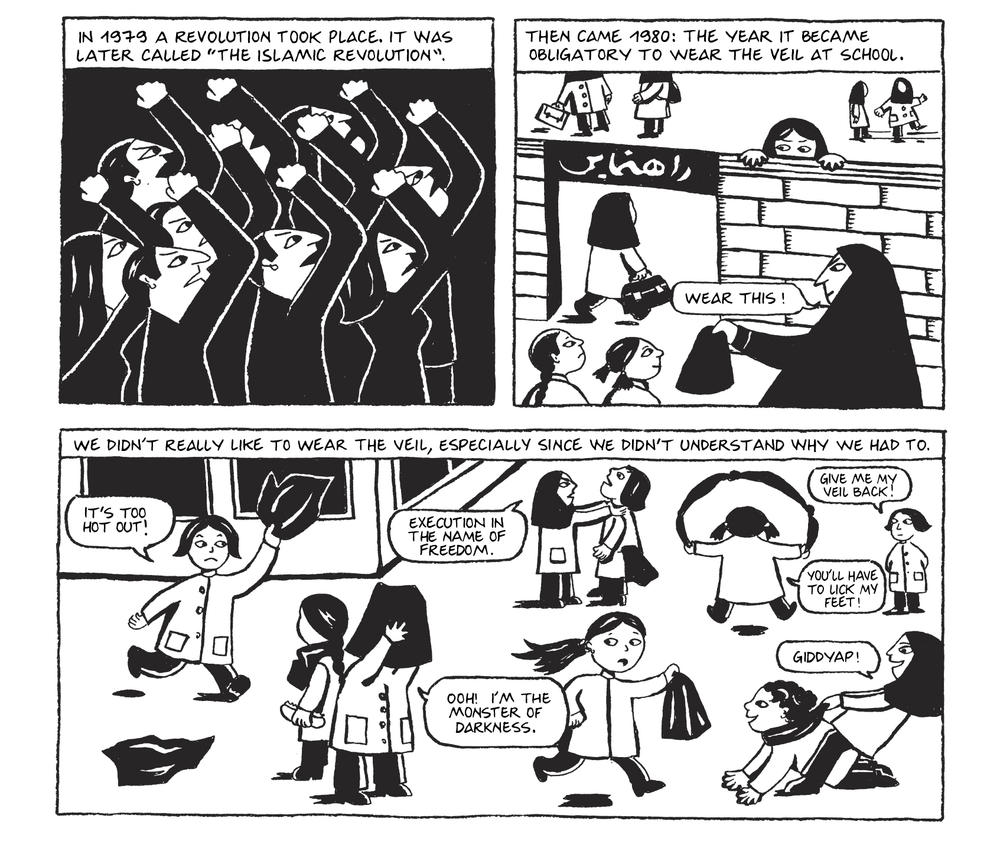

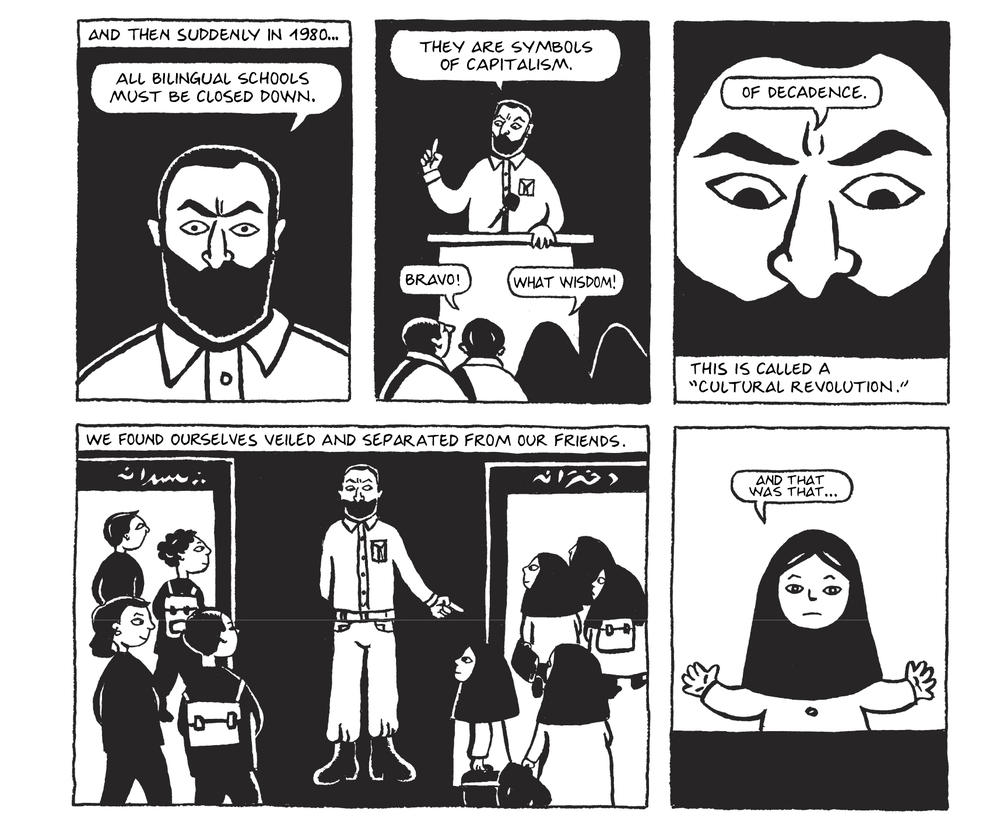

Based on the author's life and told in spare but dramatically rendered black-and-white comics, it tells the story of a young, precocious, outspoken girl who grows up in Iran during the 1979 revolution — and its tumultuous aftermath, including the Iran-Iraq War. She, her family and others around them struggle to adjust to living in the new Islamic Republic, with its oppressive rules. Many of them also rally around one another, putting their survival and comfort regularly on the line for the sake of love and self-determination.

The changed laws in Iran famously included compulsory head coverings in public for all women and girls over the age of 9, regardless of personal beliefs. But, among other things, the laws also decreased the ages at which girls and boys were allowed to marry as well as limited the rights of women to initiate divorce and retain custody of their children. As of late, Satrapi, who has not returned to Iran in over two decades, has been back in the news. This is largely a result of the ongoing protests and civil unrest catalyzed by the death of a 22-year-old Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, in September 2022. Amini died while in police custody, after being detained for the way she was wearing her head covering.

The rekindled public opposition to religious authorities in Iran has unsurprisingly led back to Satrapi and her work. "What I have lived, the youth is living now," she said in an interview with The Guardian last fall.

The cartoonist, who has described her autobiographical comics as an ode to her home country, first published the memoir in four installments, between 2000 and 2003, in France, where she moved after leaving Iran when she was still in her 20s. The work was put out in two volumes in an English translation shortly thereafter. In 2007, the already critically renowned Persepolis broadened its reach when it was adapted into an animated film, co-directed by the author — albeit after some hesitation — and ultimately earning a Jury Prize at Cannes. The film, which includes the voice of famous French actress Catherine Deneuve in the role of Marjane's mother, was promptly condemned by Iranian authorities.

Persepolis has a long history of garnering controversy, and well beyond the author's home country. In 2014, the book was second on the American Library Association's list of most frequently challenged books. The work was first taken to task in the U.S a year earlier in the Chicago Public School System, for its inclusion in a 7th-grade curriculum. It was deemed by its challengers as inappropriate due to its "graphic language and images," including several brief scenes documenting the torture of political prisoners — situations young Satrapi learned about as a child when she overheard adults around her. In the book, the related images, drawn in Satrapi's characteristically unadorned but bold illustrations, are scenes that take place through the imagination of a young girl trying to grasp what has been happening to the adults in her life.

"I take the book's banning as a huge compliment," writes Satrapi in her introduction to the 20th anniversary edition, which collects both English language volumes and also includes a new cover image. Over time, the memoir — both as a book and film — has elicited strong reactions for a host of reasons, many of them perplexing, even contradictory. They include, for example, the work's supposed depictions of sexuality ("I still don't know where those scenes are," Satrapi quips in her introduction); of communism (Marx is a cartoon character — with a keen sense of humor — in young Marjane's imagination); its general religious imagery (Marjane's version of God is downright garrulous at times, and in fact, as the young protagonist notes, looks a whole lot like Marx); and its Islamic content, which has been described by some as promoting Islam, by others as Islamophobic.

These challenges, outnumbered as they are by the readers and educators who have adopted the book into their course content and brought it into countless local and home libraries, are a particularly telling response to a work that, at its heart, is about growing up with and through books. In fact, from early in the memoir, young Marjane is pictured as a girl happily surrounded by towers of tomes. Like her frequently depicted loving and judicious parents, or her cheeky but wise grandmother, they offer yet another affirming, if singularly metaphorical, embrace in an otherwise hostile and dispiriting environment.

Indeed, over the course of the work, the protagonist turns to books at pivotal moments, particularly when she is feeling overwhelmed or confused about events unfolding around her. When her parents send her to Austria on her own, at just 14 years old, in order to continue her schooling away from the terrors of state and institutional authorities, her mother assures her: "Above all, I trust your education." As readers we know that the education to which her mother refers is largely unofficial. It is the one shaped by the rich Persian culture and history passed onto her by the bibliophiles and nonconformists in her orbit. Later, far from home and a bit older, she burrows back into books when she needs to orient herself, as when the pressures to assimilate feel overwhelming. Books help Marjane find a way back to herself, not because they tell her what to think but because, on the contrary, they remind her that — equipped with all kinds of information, ideas and stories — this decision will always be hers.

As a memoir told in comics that are both comical and also deeply serious, sometimes at the same time, what might potentially bewilder certain audiences is the unorthodox packaging of this complex and deeply moving story. Told through the eyes of a heroine whose moral compass is better defined than many of the adults around her, even as her naiveté is a source of endearment as well as amusement, Persepolis reminds its readers that children and teens are more often tuned in to the ways of the world than the adults around them are willing to admit. It's exceptional — and perhaps for that reason a bit unsettling — when a piece of art, or literature, can so thoroughly capture that basic, but easily forgotten, reality.

Tahneer Oksman is a writer, teacher, and scholar specializing in memoir as well as graphic novels and comics. She lives in Brooklyn, NY.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.