Section Branding

Header Content

60 years since his landmark 'I Have a Dream' speech, a new biography takes fresh look at King

Primary Content

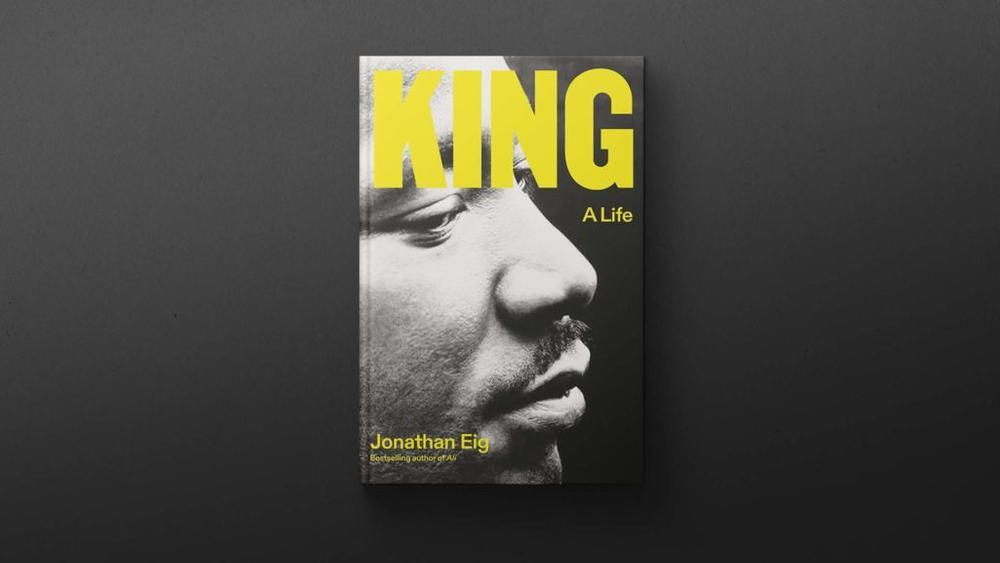

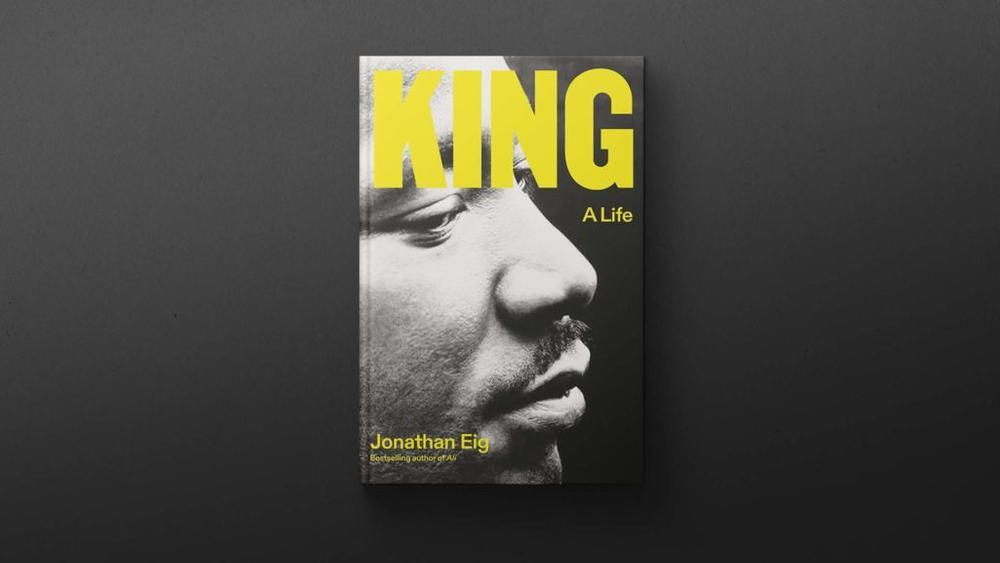

A newly published biography about one of history’s most towering figures from Georgia is being described as the first major biography of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in decades.

King: A Life by Jonathan Eig comes 60 years after the civil rights icon’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Journalist and best-selling author Jonathan Eig spoke with GPB's Orlando Montoya.

Orlando Montoya: First of all, there have been so many King biographies. What makes this one different and what new insights does it share?

Jonathan Eig: Well, I wanted to write a book that would help people remember that King was a human being, not always a monument, not always a national holiday. And there are still people in Atlanta who knew him well. And well, the first thing I did was interview a lot of those people. And I was struck by the fact that they knew what he sounded like, what he felt — what it felt like to be in the room with him. And I wanted to write a book that might make people feel like they were in the room with him.

Orlando Montoya: There's a lot of new information in the book, and we can't talk about it all. But I want to ask you about some of the revelations making headlines. One is that President Johnson knew about FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover's campaign to undermine King but did nothing to stop it. Why?

Jonathan Eig: I think he was enjoying the gossip. He enjoyed having power over people. He enjoyed having more information on people, even if they were not necessarily his political rivals. Even if they were people that he allied with and worked with, he still liked having information that he might use to control that relationship.

Orlando Montoya: Tell me about how you researched this book in terms of the new information, because there's so much that has come out in the last 30, 40 years.

Jonathan Eig: Well, as I said, I began by interviewing as many people as I could who knew him. And once I began that process, I started looking at archival collections. I found an unpublished autobiography written by Daddy King, Martin Luther King Sr., and that had a lot of new details about the Kings' childhood in Atlanta and about Daddy King's upbringing in Stockbridge, Ga.

Orlando Montoya: You do focus a lot on Daddy King. King Sr. What new do we learn about their relationship and how the father influenced his son?

Jonathan Eig: The relationship between Daddy King and MLK is a fascinating one. It's clear that they love each other, that they pushed each other. But Martin Luther King Jr. always has a little bit of fear of his father and really hates confrontation with his father. It's funny to think about the fact that one of our great protest leaders is averse to conflict, and not just with his father, with any father figure, with people like Roy Wilkins of the NAACP. King really tries at all costs to avoid conflict. And I think that goes back to his difficult relationship with his father. You know, Daddy King spanked the kids sometimes in the front yard or the backyard where neighbors could see. And he was very upset when his son began to risk his life in the civil rights movement and wanted him to come home and wanted him to give up the leadership of the Montgomery bus boycott. But Martin Luther King, as hard as it was for him, did stand up to his father in his own way and, you know, forged his own path.

Orlando Montoya: And even though I knew generally where this path was going, there's a narrative sense, the way you write it that leads some doubt: “Is he going to become a minister? Is he going to go to Montgomery?” Did you find that hard to do with the man who's so well known?

Jonathan Eig: When you write a book like this, you have to pretend that you're starting from scratch, that nobody knows the story and you have to tell it the way it deserves to be told, because we don't know. Dr. King didn't know that he was going to become the leader of the civil rights movement. He wasn't looking for that job. This is part of the story. And part of my job as the writer is to make you feel like you're living this along with Dr. King, that you don't know the conclusion because he didn't know the conclusion.

Orlando Montoya: Let's talk about the “I Have a Dream” speech for a moment. One thing that I didn't know about it, which you document, was how unprepared King was for it mentally. Can you explain?

Jonathan Eig: Well, he didn't write the speech until he got to his hotel in D.C. the night before. And he was up late that night working on it. And when you read the draft that he submitted — and he turned it into reporters before the speech so they could have a copy of it and they could get, make their deadlines — it's a fairly political document. It's powerful, but it doesn't soar with the kind of rhetoric that we're used to. It's more of a political speech than a than a religious one. And King's sermons were really usually what he was best known for, of course. But as he finished the written portion of the text, he decided he wasn't done yet and he was going to blow past the time limit they had set on him and he was going to extend. And that's when he said, “And today, I have a dream.” And —

Orlando Montoya: That was Mahalia Jackson, who cried it out from behind.

Jonathan Eig: Well, I discovered something a little different. Many people have reported over the years that Mahalia Jackson cried out and inspired him. And then King, hearing Mahalia, decided to go on to do the “I Have a Dream” speech, which she had heard him give earlier in Detroit. But that's not true, actually. What happened was that King decided on his own — and I obtained a copy of the master recording that Motown made that day, and you could hear every word out of Mahalia’s mouth. What actually happened is that King finished his speech, began “I Have a Dream” and then, about the second or third time he said “I have a dream,” Mahalia echoed him and said, “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” And over the time, that story has been changed a little bit to give Mahalia credit for inspiring him. But I don't think that's actually what happened.

Orlando Montoya: Another thing that people talk about over and over again with the speech is where he tried it out before. I'm from Savannah, as you know, and there's a church down there that says, you know, that there was a version of the speech here. And there's another version of the speech there. What can you say about that?

Jonathan Eig: King was not the least bit concerned with originality when he gave a sermon or a speech. He liked to practice things to try them out on audiences. This is what all preachers do. Try it out on an audience, see what works. And he tried the dream speech in Savannah, improved on it, tried it again in Detroit. It came originally, it was inspired greatly by a Langston Hughes poem. After trying it in Detroit, getting a great response — at that point, it was the biggest rally he'd ever spoken in front of, in Detroit. He brought it to D.C. and thought, "Well, it worked in Detroit, it worked in Savannah. Here I go again."

Orlando Montoya: And in coming up with new ways to tell stories that people might know already, I want to point out how you talk about the “I Have a Dream” speech in the book by focusing on one person from that person's point of view. Why did you decide to focus on an audience member?

Jonathan Eig: Well, there's a problem with this storytelling that I encountered: How am I going to write about the “I Have a Dream” speech in a way that feels as powerful as the Dream speech itself? I can't. I cannot, on the printed page, convey the magic, the power, the majesty of that speech. So I had to do something different. And I decided to take the lens off of Dr. King and show how that speech echoed with the people in the crowd. So, I wove in three stories, really: The story of Dr. King and the words and the speech he's giving; along with the story of a teenage girl from Chicago, Francine Washington, who just at the last minute got on a train and decided that she was going to come there because she was inspired by what she saw King doing. She’s a Black girl. And she wanted to believe that King could actually change her life. The other, third person I wove in is the white bodyguard who's standing next to King as he gives his speech. If you look in the photos, you'll see there's this tall guy in a park ranger hat. His name is Gunny Gundrum. And I thought, “Who's that guy? Why is he in every photo of King giving his speech?” And at one point, if you watch the video, Gunny reaches in and adjusts the microphone in the middle of the speech. Who has got the nerve to stick his arm in front of Dr. King when he's giving the greatest speech of his life? But Gunny did. So I tracked him down to and talked about what it was like for a white man who had never met a Black person until he went into the Army. What was it like for him? How did that speech change his life? So I wove those three stories into the chapter.

Orlando Montoya: Jonathan Eig, it's a fabulous read. And I want to thank you for coming in and talking about your book, King A Life by Jonathan Eig.

Jonathan Eig: Thank you.