Section Branding

Header Content

It's time to rethink Rudy Giuliani and his claim to discover RICO

Primary Content

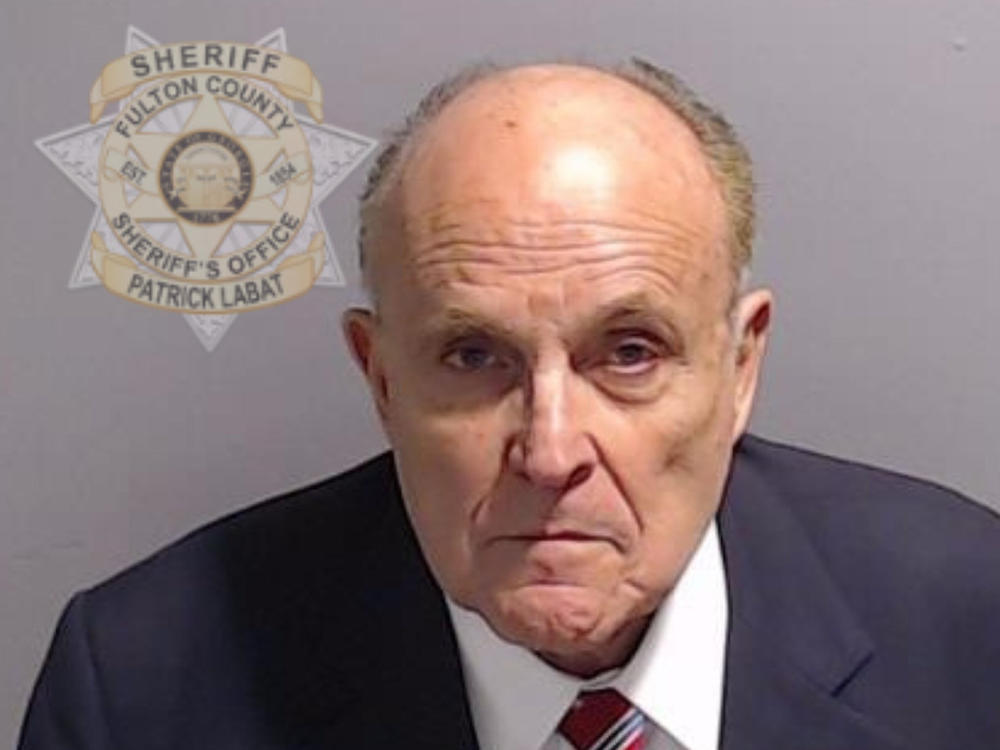

Rudy Giuliani's surrender to Fulton County Jail last week on charges that he helped overturn the 2020 election in Georgia represented a grand, almost poetic fall from grace for a man once called "America's Mayor."

Giuliani is facing 13 charges as part of the sweeping racketeering indictment, one of the case's 19 defendants set to be arraigned on Sept. 6. Georgia's racketeering law stems from a similar federal statue that Giuliani leaned heavily on in a federal case against leaders of the American Mafia when he was a federal prosecutor in New York in the 1980s.

Giuliani has long claimed that he dreamed up the idea of using the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act to target mafia families in the U.S.

A New York Times article from 1989 quotes him saying, "'Using it against the [Mafia] commission,' Mr. Giuliani said, 'that was an idea that no one had until I developed it and went down to Washington and started talking about it. And I came to the office with it.' "

The self-proclaimed "pioneer" of RICO now finds himself the defendant in a RICO case.

The irony seemed almost too rich — and that's because it is, according to two former prosecutors who worked on RICO cases in the 1970s and '80s and whose work overlapped with Giuliani. They say the public has been the victim of Giuliani's own mythmaking.

"Giuliani is a blowhard and a self-promoter," said Edward McDonald, the former attorney-in-charge of the Federal Organized Crime Strike Force in Brooklyn. He is now a criminal defense attorney.

RICO's origins, from prosecutors who were there at its start

The 1989 New York Times article also said Giuliani had a tendency to overstate his accomplishments.

"He has long asserted he invented the use of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, to pursue the Mafia commission. In his interview, Mr. Giuliani repeated an account he has told many times about formulating the idea before becoming U.S. attorney, when he read a book by Joseph Bonanno Sr. about his life in the mob," the article said.

Giuliani has frequently rejected attempts to thwart his version of the RICO origin story.

In that same article, Giuliani is quoted as saying others' versions of events were wrong. He says to the Times interviewer, ''Those people are now trying to recreate a good idea.''

The reality is University of Notre Dame law professor G. Robert Blakey drafted the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970 of which RICO is a part.

Before RICO was on the books, it was considered unfair and prejudicial for a prosecutor to say a defendant was a member of the mafia or some other criminal organization when they were prosecuting them for a singular crime, McDonald said.

"RICO comes along and says that in order to prove the RICO violation you have to prove that there is an association of fact or criminal enterprise that is involved in criminal activity," McDonald said.

The law enabled prosecutors to pursue a defendant for multiple crimes, he said.

"You had to prove two or more crimes were committed as part of a pattern of racketeering activity, which is necessary to get a criminal conviction under RICO," McDonald said.

For years after the national statute's inception, the Justice Department was very cautious in authorizing the use of the statute because it was such an incredibly powerful weapon for prosecutors, McDonald said.

Officials at DOJ "were concerned that the courts would view the Justice Department as going overboard and they were concerned that the statute could be found to be unconstitutional, or that the courts would construe the statute in a very narrow way," he said.

By 1977, when McDonald started working at the DOJ, RICO was being proposed as a useful tool for prosecutions against Mafia figures, he said.

"The reason that they moved slowly on it was not because it was waiting for Giuliani to to discover it," McDonald said. "It was only after they got favorable decisions in the appellate courts did they feel emboldened to authorize more and more criminal prosecutions" before Giuliani became U.S. attorney in 1983.

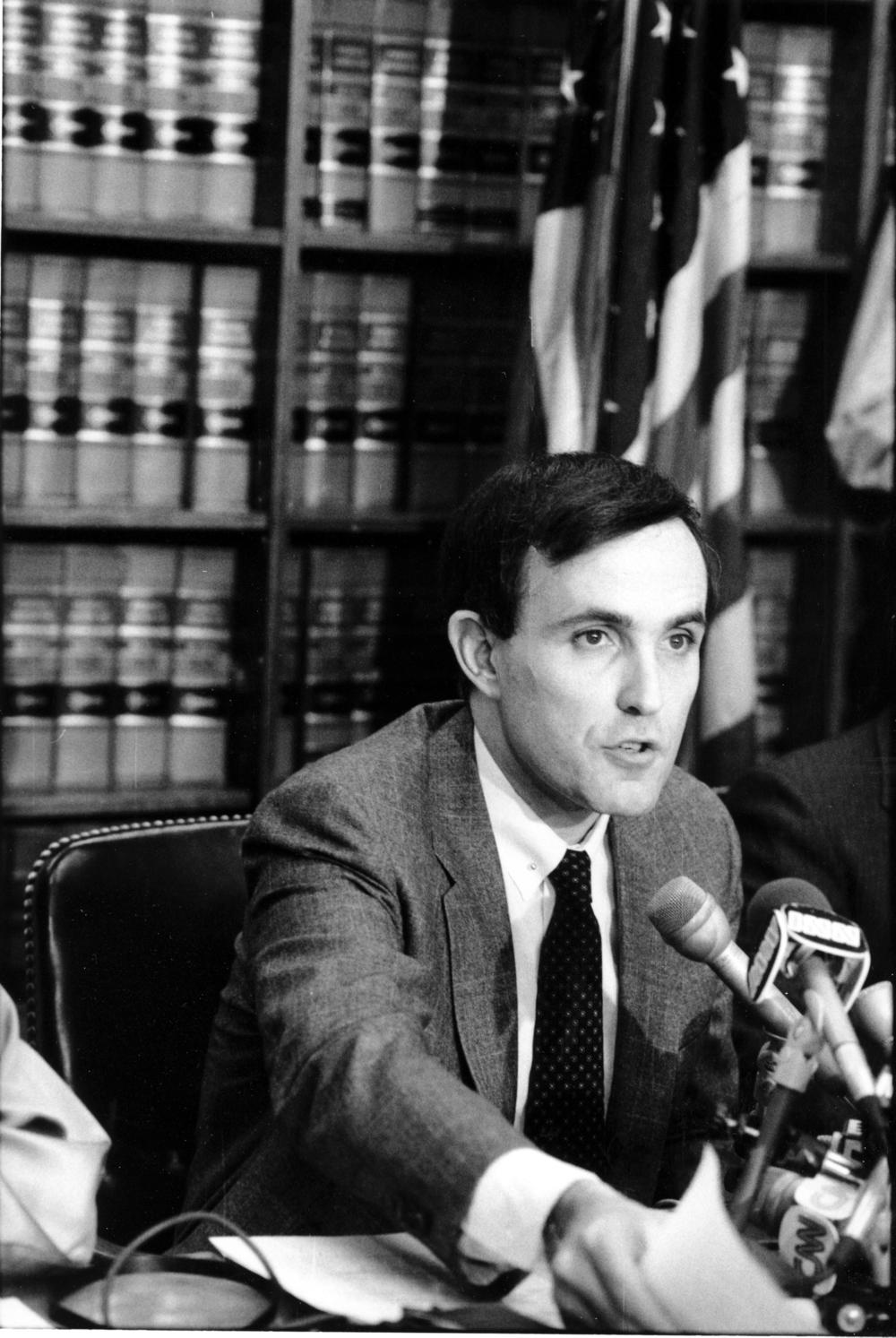

Many of the RICO cases brought in the Southern District of New York were started by Giuliani's predecessor in that office, John S. Martin Jr., said Walter Mack, the assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York from 1974 to 1990. Mack was also the chief of the office's Strike Force Against Organized Crime from 1981-1984.

Martin wrote an op-ed back in 2007 in The New York Times calling Giuliani out for his claim to have turned around the Manhattan U.S. Attorney's Office after he left.

"This is not to say that Mr. Giuliani was not a good trial lawyer and that he did not provide effective leadership. But the important cases prosecuted during his tenure did not result from some unique initiative or insight on his part," Martin wrote.

Giuliani and the Mafia Commission case

The genesis of the myth that Giuliani was the one to "discover" RICO is tied to the mafia commission trial that began in 1985.

This case used evidence gathered by the FBI against several organized crime figures, including the leaders of the New York City Mafia's Five Families. They were indicted under RICO and for extortion, labor racketeering and murder, among other charges.

Martin wrote in his New York Times op-ed that the idea to prosecute the heads of the mafia came from "the head of the criminal section of the F.B.I.'s New York office in a meeting with me and my staff approximately a year before Mr. Giuliani took office," he continued in his article. "By the time he was sworn in, the office was laying the groundwork for that case and had in place wiretaps on three of the five organized-crime families in New York City."

The case was a success with eight defendants convicted after a 10-week trial.

It was the first case of its kind to target the so-called "board of directors" of the Italian American Mafia.

At the end of the day, the impact of the Mafia Commission case can't be overstated, according to Scott M. Burnstein, an organized crime historian and writer.

"I would say it was game over for what would have been called the golden era of the Mafia," Burnstein said.

The case helped throw Giuliani into the national spotlight and did help burnish his reputation as a legal scholar, he said.

The downfall of "America's Mayor"

Giuliani especially won hearts when he led New York City in the devastating aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 9/11 for which he was dubbed "America's Mayor."

Of Giuliani's apparent fall from his pinnacle, McDonald said he "shouldn't have had that grace to begin with because a lot of it was was a bunch of self-promotion and nonsense."

Mack said, "To me, it's a tragedy."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.