Section Branding

Header Content

A concert audience of houseplants? A new kids' book tells the surprisingly true tale

Primary Content

In the latest children's book from mother-daughter duo Julie Andrews and Emma Walton Hamilton, a village subdued by a mysterious purple fog finds joy again by serenading an audience of appreciative houseplants.

The protagonist is young Piccolino, whose father is the maestro of the town opera house. Even though the fog is keeping people at home, the pair continue cleaning the empty building. One day Piccolino tinkers with the piano, and notices that the drooping plants in the lobby seem to brighten at the sound of music.

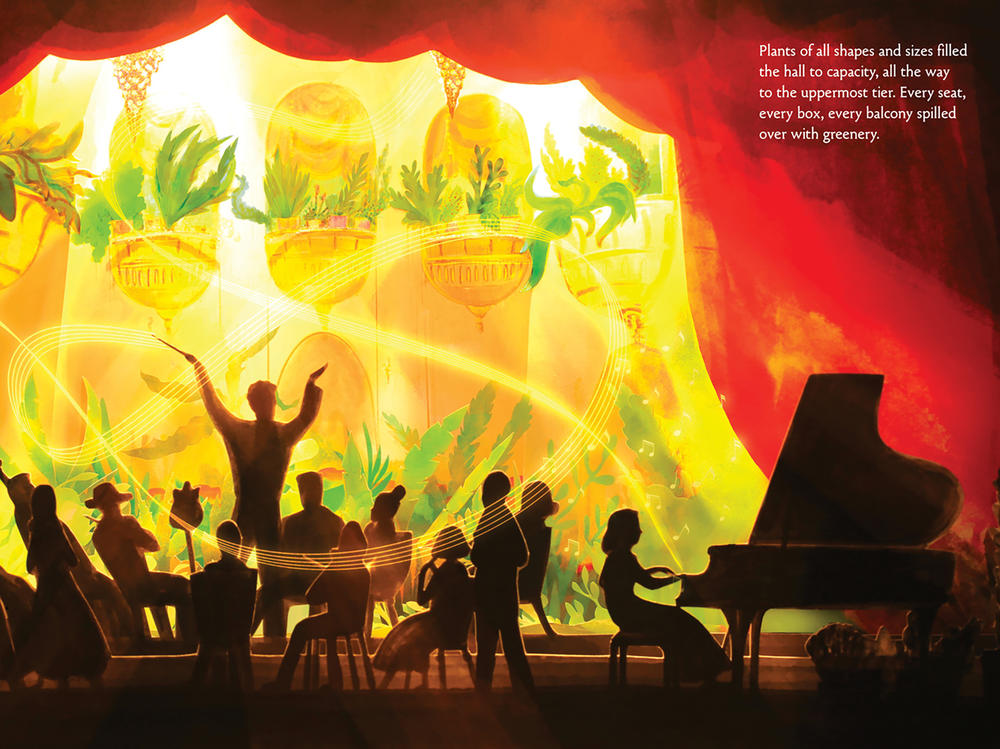

So they embark on a mission, collecting every houseplant they can find and enlisting orchestra members for a special concert. When the day comes, the unsuspecting musicians take the stage and tune their instruments. Then the velvet curtains open to reveal an auditorium full of greenery.

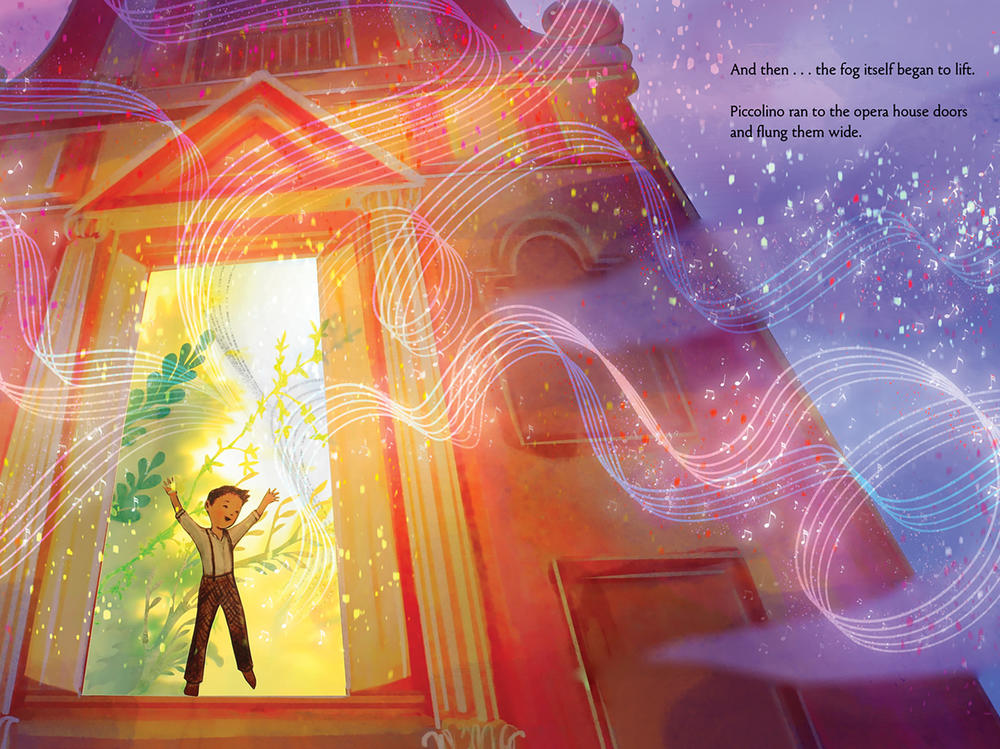

"The astonished musicians began to play tentatively at first, but gradually building in strength and tempo as the joy of making music again lifted, their spirits and the plants responded in kind, nodding and swaying, their stems standing taller and firmer, the leaves rustling in appreciation," the book reads. "And then the fog itself began to lift."

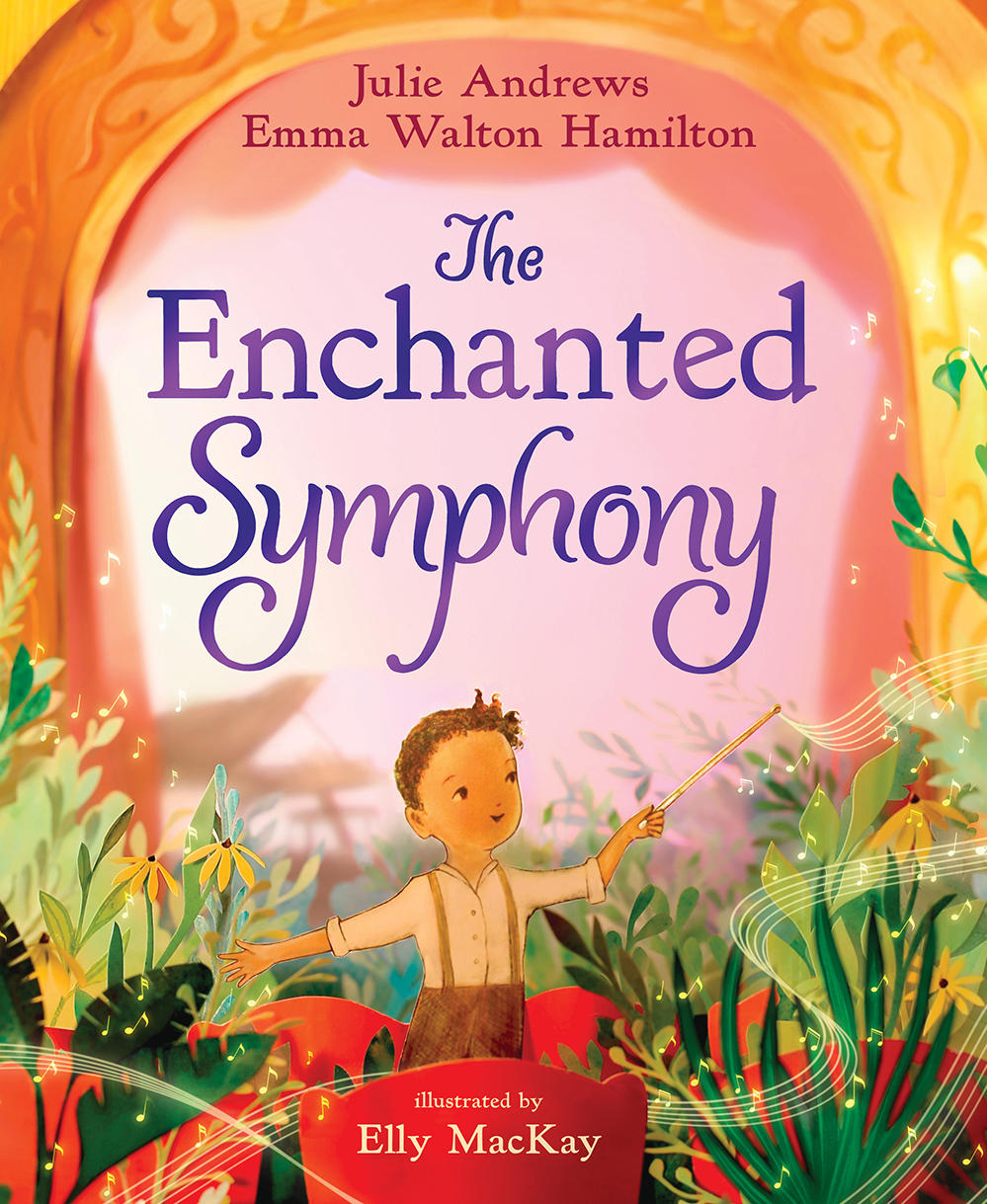

As whimsical as it looks, and as fanciful as it sounds, The Enchanted Symphony is inspired by a true story.

In June 2020, after several quiet months, Barcelona's Liceu opera filled its more than 2,000 seats with plants for a string quartet performance that was also live streamed for humans and quickly went viral.

Andrews and Hamilton were inspired by the photos and videos of the event: the red and gold opera house packed with lush green leaves, the announcement asking audiences to silence their cell phones, the way the houseplants seemed to stir with applause at the end.

"We often write books about the arts and about nature, and this seemed to be such a perfect marriage of those two passions of ours," Hamilton said. "So we tried to imagine what might cause an opera house to be filled with plants instead of people. And we came up with the little fable that is The Enchanted Symphony."

Andrews, Hamilton and illustrator Elly MacKay pulled back the curtain on their creative process in a Zoom interview with NPR shortly after the book's release in September — the first time all three had spoken face-to-face.

"I think that a lot of times illustrators and the writers of books don't get enough time to chat and talk to each other, and quite often it goes straight through the editor or the publishers," Andrews said. "But in our case, we love talking to our illustrators. And in this case, it was a delight because Ellie got everything that we asked for and then some."

The authors didn't want the book to be specifically about the pandemic. Instead, they were going for more of what Hamilton describes as "a fairy tale with a timelessness to it." That's why they created the fog.

Hamilton said it represents not necessarily the virus but "anything that threatens to distract us from those kinds of simple pleasures that really happen to be the most meaningful in life." And that's one of the messages they hope readers will take away from the book.

"We hope readers will, first of all, take a new curiosity or appreciation in music and in nature, of course," Hamilton said. "But we also hope that it will invite readers to think about what matters most to them, what values are important enough to be a primary focus in their lives."

Creativity makes the mother-daughter partnership sing (and tea helps too)

Andrews and Hamilton wrote the book — one of three they penned during the pandemic — at Andrews' dining table.

Their typical process involves a lot of brainstorming, outlining and writing out loud, a fair bit of "finishing each other's sentences" and copious amounts of tea — always PG Tips English Breakfast.

"If I can say it on public radio, don't ever forget the benefit of a bathroom break or a break to make a cup of tea," Andrews added. "Because quite often we'll be stuck ... And when we come back, one of us will say, 'I got it. I think I know the way out of this.' And it's that tiny break giving your mind the freedom to create on its own without being pushed in any direction."

Hamilton and Andrews have written more than 30 children's books together. When they first started, decades ago, they lived on opposite coasts and would spend hours writing over the phone until their necks were stiff. Andrews would begin at 6 a.m. in her nightgown, spritzing herself with perfume to feel more awake.

Hamilton said they work so well together in part because they both come from creative backgrounds, collaborated in mediums like theater and film before they took up writing and have a "shared sensibility about storytelling and creative problem-solving."

Andrew thinks it's also because they have different strengths. She described her daughter as "the nuts and bolts of our books" and herself as "more the flights of fancy."

They say their philosophy in moments of disagreement is "the best idea wins," regardless of who came up with it. And they learn something new with every book.

"I think overall what we have learned most from working together is ... the degree to which being creative casts a kind of a magic spell on our relationship, on our lives," Hamilton said.

They say the time spent problem-solving together, running up against a deadline, takes pressure off other stressors that mothers and daughters typically face, from busy calendars to health concerns to family drama. It distracts from the tensions of everyday life, they say, and also helps them get through them.

"It's like creative weightlifting," she added. "It strengthens our relationship."

The illustrations look layered. They started as a mini 3D set

Andrews and Hamilton said they fell in love with MacKay's work "because of its luminosity."

"We knew we needed to find somebody who could manage to convey both the fog and the world hidden behind, blanketed by the fog," Hamilton said. "But then when we found out about what her particular technique was, we were completely blown away because it completely supported the theme of our story."

MacKay starts by building miniature sets, complete with the scenery and characters. Then she lights and photographs them, giving the images a more three-dimensional quality.

She said this book posed a particular challenge because she had to create a theater inside of her miniature set.

She thought about things like how to layer the houseplants further away from the stage to create a sense of depth and how to filter light through the branches of a tree onto the kids playing beneath it. She also grappled with the balance between the vibrant colors that are so necessary in kids' books and the muted mood of parts of the story.

"I wanted the gloomy scenes all to have this kind of purple feel, lots of purple tones, and then the joyful scenes to be lit up with greens and reds and golds," MacKay explained. "And I used shadow quite a bit to contrast the darker times with the lightness and play that came with the music."

Andrews, Hamilton and MacKay communicated through their editor, exchanging feedback and revisions by mail to bring their shared vision to life. MacKay tweaked certain illustrations by first moving things around in her sets. And Hamilton and Andrews pared down the text to let the images do more of the talking.

At one point, the writers suggested fewer flowers and more houseplants in the audience.

"So I got busy and made more and more houseplants and filled my little theater full of houseplants," MacKay said. "It's so much fun to just play and create in that way."

MacKay said she imagined her 11-year-old son as Piccolino while she worked on the story. A real-life green thumb, he grew trees and then sold them to neighbors in his front yard, similar to a lemonade stand. And there are now trees throughout the community that he started from seeds.

The authors learned of MacKay's connection to the story for the first time on Zoom. For Andrews, it called to mind the time years ago when she asked her youngest daughters what they would want to plant in their garden. One said strawberries, and the other said ratatouille.

The arts are powerful — and these three would know

All three reflected on the importance of art, both in their own lives and their hopes for inspiring young readers.

MacKay, for instance, grew up in Canada in a home with two artists. She remembers going to the Stratford Festival to see theater every year. At her mom's invitation, other neighborhood kids would come over twice a week to build sets and props out of boxes. Then they would put on a performance at the end of the summer.

"I guess it's in my soul that community and art are intertwined," she said.

Hamilton, who co-founded a theater in New York and also works as an editor and arts educator, views art both as the great unifier and the great leveler. That's because it's accessible and meaningful to all, she says.

"You just have to show up and experience it. And for us, it is unique in that way," she added. "It is the great joy that unifies us as a society, and holds up a mirror to us..."

"...And crosses all boundaries and languages," Andrews chimed in. "And it can be mutually enjoyed and make us more unified."

Picture books for children are especially important, Hamilton says, describing them as both windows and mirrors to the world.

Andrews agrees. She grew up in a musical family and started performing at the age of 12, which she says opened her eyes early to the joy of sharing art with others.

"[There's a] loveliness that comes when you're old enough to know that you are giving some stimulation or pleasure to someone through your work that, I don't know, stops them worrying about a home problem or the fact that one of their children is not feeling too well or that they've got financial problems," Andrews said. "But for one evening, one afternoon, one reading of a book, they can forget all about it and be nurtured."

They pointed in particular to the growing body of research showing the academic, behavioral and other benefits of exposing children to art.

Andrews, who tested her drafts out first on her own children, encourages parents to introduce their kids to the arts early on — and support their own creative endeavors.

"Let your child try to write, don't ever judge them," she said. "Just let them put something out on paper if they're interested, because it is such a lovely outlet, and you learn so much from it. And it inspires children to go further."

The broadcast story was produced by Samantha Balaban and edited by Melissa Gray.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.