Caption

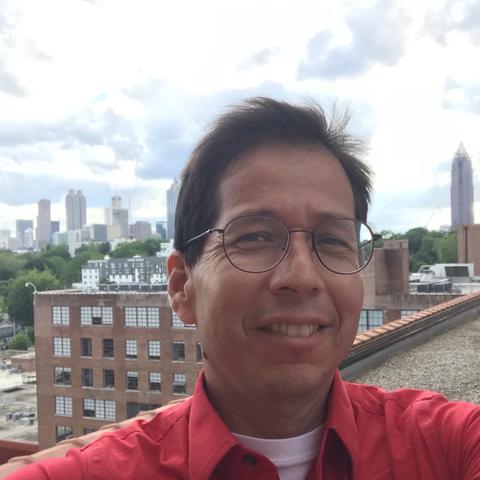

Convicted when he was 13 for murder, Michael Lewis smiles for this photo with the woman whom he credits for turning his life around, author and activist Elaine Brown, moments after Lewis was released from the Macon Transitional Center.

Credit: Leigh Shrope