Section Branding

Header Content

From opera to breakdancing and back again: Jakub Józef Orliński fuses two worlds

Primary Content

A breakdancing opera singer may sound like one of the most incongruous things out there. But not for Jakub Józef Orliński.

"Not to brag, I might be the only one," the Polish countertenor told NPR's Leila Fadel in an interview with Morning Edition.

Orliński sings in a falsetto voice that's in the highest range possible for a man, close to a female mezzo-soprano or contralto. Most of the repertoire he sings is from the Baroque period.

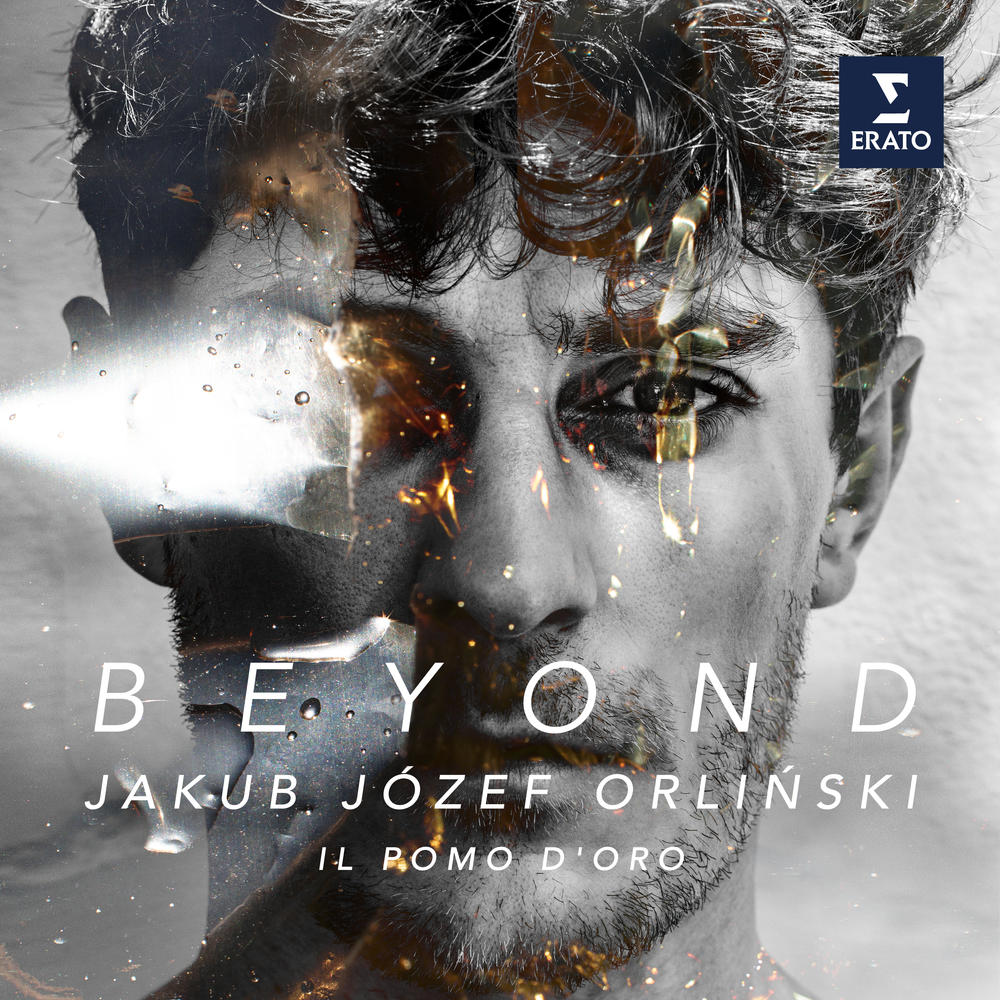

His latest album, Beyond, with il Pomo d'oro orchestra, features arias from the earlier part of that era in the 17th century, as it overlapped with the end of the Renaissance in Europe. Ten of the tracks are world-premiere recordings, despite the music being composed hundreds of years ago.

"Composers of that time, really, they could capture the emotions in a very pure and authentic way... Love or hate, anger, frustration, there's so much to show through this music," Orliński says. "It sometimes seems like it's very complex and complicated and really kind of structured in a way that nobody understands it. But actually, it's quite simple. You have to know, of course, a lot of rules to be able to perform such music, but you don't need to know all of those rules to receive it."

All it takes, Orliński says, is to listen with open arms.

He stumbled into singing in a high range during his time in an amateur choir in his native Poland when they began taking up music from the Renaissance. The collaboration and "musical intelligence" necessary to perform these works was "truly magical and extraordinary," Orliński says.

As a teen, he would listen to the punk rock bank The Offspring. But he also enjoyed pieces by 16th century composers Thomas Tallis or Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.

"I could sense or I could feel something that I could not find in the pieces that I was listening by Britney Spears or Destiny's Child," he explains.

At the same time, Orliński was a skater kid who also did capoeira, freestyle skiing and snowboarding and played tennis. When he started breakdancing in his late teens, it was "an enlightenment," he says. "It combined acrobatics, it combined music and personal expression, so it's an art form."

Recently, he's showed off both skills on stage. For his role as prince Athamas in Handel's Semele at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich in July, he sang but also did handstands and spins. Claus Guth's production is set to get its New York premiere during the 2024-25 season at the Metropolitan Opera.

It all works because Baroque music can be very dancy.

"When I'm listening to it, I'm vibing, I'm really vibing and you want to boom, go and dance," Orliński says. "When I'm in my practice sessions with my breakdance crew, sometimes I put some classical instrumental music and I invite them to actually explore that because music dictates movement. And if you listen to hardcore rap, it dictates a completely different style of movement and it inspires you to do different things. When you listen to house music, it is very jumpy, very energetic in a way that you do completely different things."

Musicologist Yannis François, a frequent collaborator who is himself a bass-baritone singer, helped conceive the album, which at times has the feel of a concert thanks to improvised transitions and a deliberate succession of certain keys or musical themes.

François uncovered manuscripts by Italian composer Giovanni Cesare Netti (1649–1686) during his research and on the album he spotlights an especially sumptuous scene from his opera La Filli. Besides this rare gem and others by Adam Jarzębski of Poland (c.1590–1649) or Germany's Johann Caspar von Kerll (1627–1693) — both composers whose works were largely lost — there are well-known tunes by Caccini, Frescobaldi and Monteverdi. There's also an aria by Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677), "L'amante consolato."

"It has different colors, different shapes and different tempi in it, which I find really fascinating," Orliński says.

Strozzi was one of only a few women from that period to publish their own compositions. Even more unusual is the fact that she did so without the backing of the Church or a wealthy supporter.

"It was basically really taken by male composers, the whole scene... especially coming from Renaissance period, where women were not even allowed to sing in the church," Orliński adds.

Despite his innovative approach, Orliński insists that he's "not trying to change the world of opera," one whose audience and fundraising can sometimes lag.

"Some people, some institutions really try to sell opera as something cool. And it's not cool when you try to make something cool. It's cool when you really do your thing and you are trying to interest people in what you are doing," he says.

"If you as an artist, as a producer or a director of an institution, you strongly believe in what you do, it will defend itself."

The radio broadcast version of this story was produced by Barry Gordemer. The digital version of this story was edited by Treye Green.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.