Section Branding

Header Content

'I was tired of God being dead': How one woman was drawn to witchcraft

Primary Content

From the historic Salem witch trials to the teens in The Craft and Netflix's Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, witches have long cast a spell on Hollywood's imagination – but they're not just figments of our imagination.

People who practice witchcraft are everywhere. Just ask Diana Helmuth.

Who is she? Helmuth is a writer and aspiring witch.

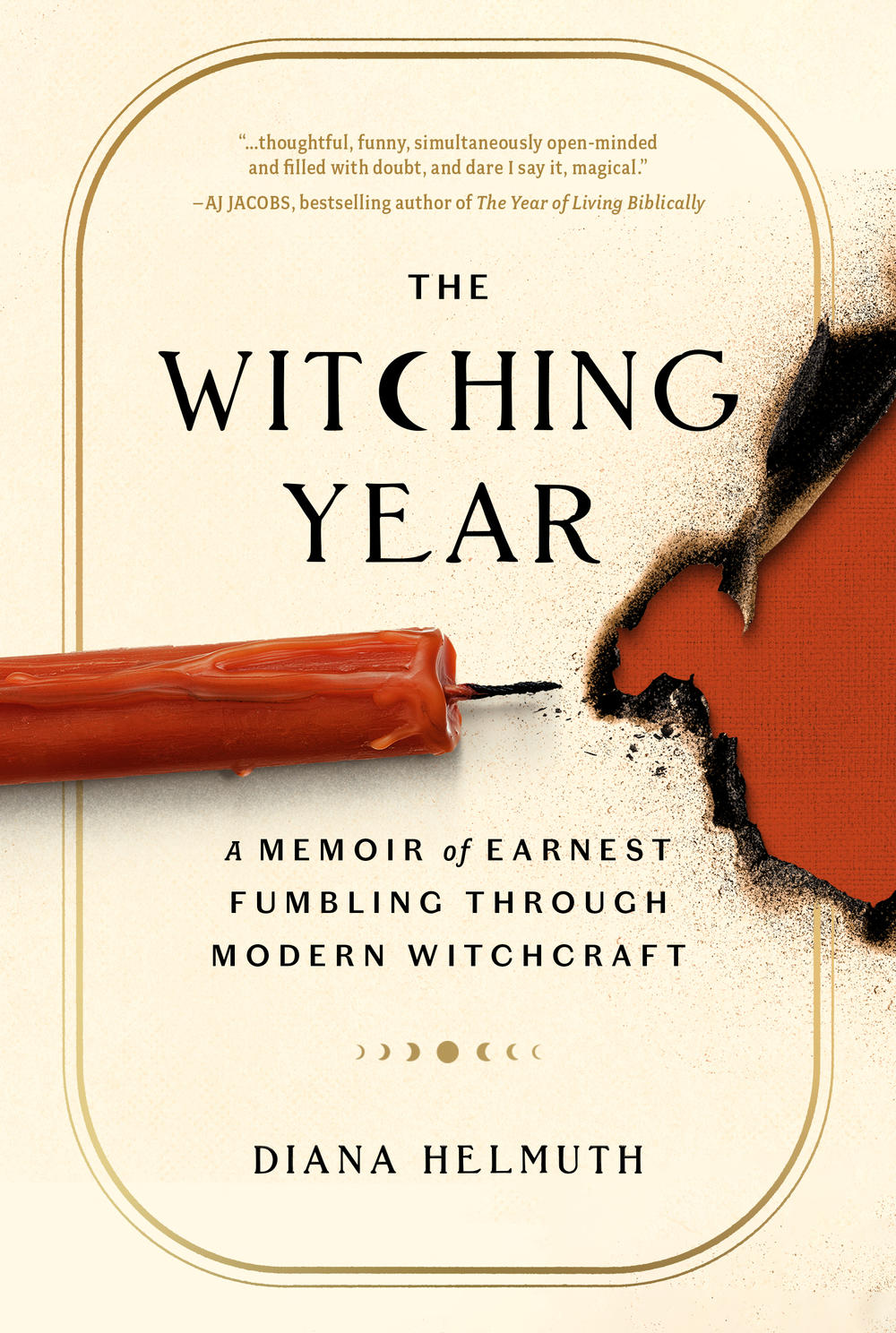

- She spent an entire year delving into the world of the occult and detailed that spiritual journey in her newest book, The Witching Year: A Memoir of Earnest Fumbling Through Modern Witchcraft.

- Helmuth was a teenager growing up in Oakland, California during the early 2000s, when she first heard about witchcraft. Her friend was a Wiccan witch, and she introduced Helmuth to the religion, and its spells.

- Still, she was a skeptic. "It was very clear to me that if you were smart, you were an atheist ... that was the undercurrent of the philosophy [I grew up with]," Helmuth told All Things Considered. "And I wanted to be smart. I wanted to be thought of as intelligent, so I rejected most religion and most spirituality throughout most of my life."

What's going on? In the midst of COVID lockdowns, Helmuth decided to spend a year as a practicing witch, consulting primary sources and talking to witches who had been practicing a long time.

- She began her journey with Wicca, a reconstructionist religion brought about in the 1950s by a man named Gerald Gardner. "It has structure to it, there are some steps. There are some rules," Helmuth says. "Wicca is very small, and witchcraft is very big."

- Witchcraft is a practice, while Wicca is a religion. Many witches don't actually consider themselves Wiccan. "In fact, Wicca is starting to be a little, I would say, outdated for a lot of people," Helmuth says. "With that said, I think Wicca has still influenced the landscape of witchcraft, at least in North America."

What's she saying? Helmuth spoke with All Things Considered about her foray into modern witchcraft.

On why she began her journey in the first place, despite being skeptical of religion and spirituality:

During COVID and, I think in general, as I got older, [I was drawn to] the idea of a self-directed religion that promised me a way to have some control over the universe.

I think increasingly we find ourselves facing things that really affect us deeply that we have very little control over: climate change, housing prices, health insurance bills, pandemics, who's going to become the president. And here's this religion — this spirituality — that says, "You can have an effect on these things that feel so much bigger than you. You just need a couple of candles and some willpower."

If I'm being really honest, I was tired of God being dead. I didn't want to feel like I didn't care about the divine anymore. I wanted to admit to myself that I did care, that I did want to feel held by the divine, but getting through the shame of that is something that is interrogated throughout the book. Like, why was that so hard for me to admit?

On a moment in her witchcraft journey where everything finally clicked:

It took me until month seven before I tried to make a connection with the goddess, who is a central figure in almost every form of witchcraft. Whether or not she's a real deity up in the sky or she's a metaphor for the interconnectedness of everything on Earth, there's this idea of a goddess. And I was hesitant around it because I didn't want to feel like I was playing make-believe. Again, this goes back to just being so afraid of feeling stupid. So I go, and I set up this ritual to try and talk to a particular goddess. And I'm by myself in my office in Oakland. I'm sitting in front of an altar that I've made out of a cardboard box. I have a stranger's playlist going on Spotify. My cat is on the other side of the door staring at me, and after about an hour, something happened. I just suddenly felt flooded with bliss. And after that experience, it became very difficult for me to continue to make fun of this part of myself that wanted to be connected with the divine. Shame just wasn't involved.

On finding her own way to practice witchcraft:

I felt I found a correct way to practice witchcraft for myself, but I — to be honest — still don't feel 100% sure about it. And something I have accepted is maybe that's the point. So I dabbled with a lot of these subcultures within witchcraft or that overlap with witchcraft, like astrology and tarot. And there are things where I'm just like, this just isn't for me.

There was one thing that really stuck with me, which were my tarot cards, which I was not expecting. My tarot cards scare me. Like, I don't like to look at them for too long. I have learned that I don't always want to ask them a question because I don't necessarily want the answer because it's not always fun, you know? Sometimes, it's terrifying. Sometimes, you don't want to look at yourself in the mirror that hard.

So, what now?

- Helmuth hopes that her book will help outsiders understand practicing witches better. She says the mainstream tends to make fun of people in the subculture, and think practitioners are silly, maybe even a bit delusional. "And really, these are just people who are trying to be more comfortable in their own skin," Helmuth says, "and also, you know, they're adopting a spirituality that centers the Earth and personal growth. And I think those are two very good things, and we should not be making fun of them."

- She also hopes that her earnest fumbling will inspire others to begin their own journeys. It's something of a "permission slip," she says. "It's OK to explore this stuff and feel like you don't know what you're doing and feel like you're probably doing it wrong and still have that journey be valid and worthwhile."

Learn more:

- 3 witchy books for fall that offer fright and delight

- Sasheer Zamata's new special is an ode to women, mental health and witches

- 370 years later, Connecticut is exonerating accused witches

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.