Section Branding

Header Content

The answer to veterans homelessness could be one of LA's most expensive neighborhoods

Primary Content

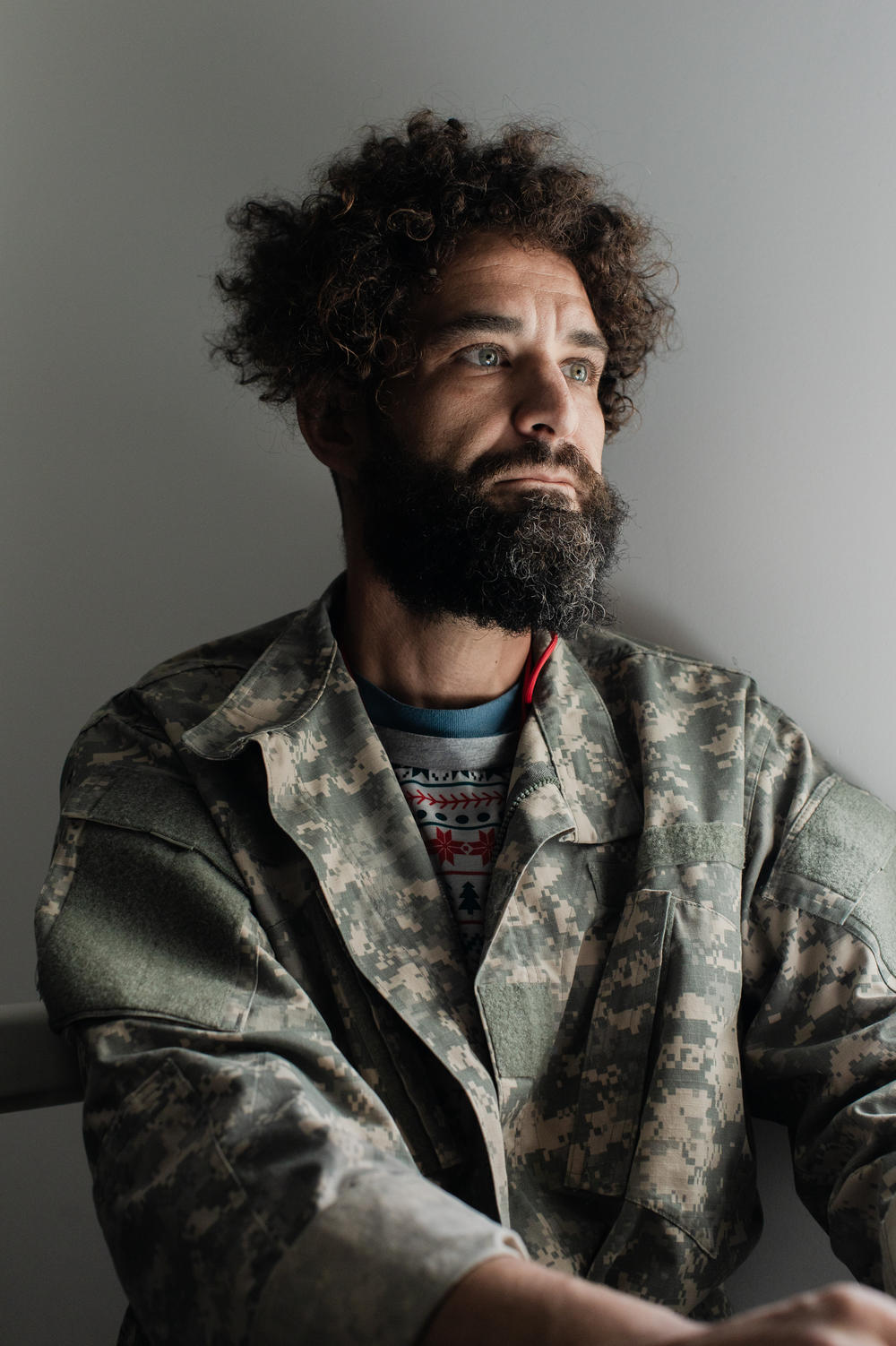

The first time John Follmer met a Purple Heart vet living on the streets after trying — and failing — to get VA benefits, it surprised him.

Not anymore.

Follmer has been doing homelessness outreach with LA's Veteran Peer Access Network for three years. His goal is to help vets on the street tap into the array of economic, health and housing benefits they've earned. Follmer's seen many vets — including two more Purple Heart recipients — who have been wrongly turned away from the Department of Veterans Affairs or don't believe they're eligible.

"It's not the lack of resources. It's the abundance of discouragement," says Follmer.

Which might explain LA in a nutshell. Los Angeles has the largest number of homeless veterans, nearly 4,000 according to the annual count. LA also has a unique asset to help them: A 387-acre facility on some of the country's most expensive real estate: Brentwood, in West Los Angeles. The sprawling campus was donated as a home for Civil War veterans in 1887. In this century veterans groups have sued the VA for leasing parts of the campus out for things that had nothing to do with vets, like UCLA's baseball stadium, the private Brentwood School and other deals, some of which turned out to be criminal.

Veterans groups pointedly asked: If the campus could host a golf course and a working oil well and a bird sanctuary, why couldn't it build housing veterans? Veterans groups sued to drive that point home, and then VA settled the lawsuit in 2015 with an agreement that plaintiffs say hasn't been enforced. Now they're suing again and the case may go to trial next year. It's left vets like Follmer skeptical.

"You can't build anything on a foundation of neglect," he says, though he's encouraged by several recently opened new buildings to house veterans on the campus.

Construction on units has begun

As the sounds of construction echo through the north half of the VA campus, it's allowing some of the long-time critics to have some optimism.

"It's more difficult to say 'you're not doing anything' when we have more than 500 units already completed or in progress," says Steve Peck, a Vietnam vet who leads US Vets, part of a consortium developing buildings for housing on the campus.

"We're getting there," he said, walking into a newly renovated 1940s Mission-revival style building on campus that now holds 59 studios and one-bedroom apartments.

The building is exclusively for vets over age 62, half of them with severe mental illness. Peck said it filled up in less than four months.

"It's a nice home. They're proud to call it home," he said. "A lot of the veterans who came in here after they were here for two weeks went to the social workers and said, 'How long do I get to stay here?' And she said this is your home. Stay here as long as you want."

Peck says much of the work over the past five years was unseen — literally underground, updating 100-year-old infrastructure. Now the work is becoming visible, with 233 units already housing vets and 347 under construction. The next site slated to open is for women veterans with children.

A vision of affordable housing for vets in one of the richest parts of LA

The "master plan" is to build a real community with a village feel, including a café and restaurant, maybe an art center. An LA metro station stop is slated to open in 2027, which would integrate the campus with the rest of the city. By then developers hope to have completed most of the target 1,200 units of housing. It's a vision of a vibrant community of affordable housing for vets living in one of the richest parts of LA.

It's also the focus of decades worth of well-earned suspicion, says Rob Reynolds, an Iraq vet. When he hears about shiny new restaurants, or a massive park-and-ride garage for commuters at the new metro station, it sounds like history repeating itself.

"A lot of these entities that are on the land, that are unrelated to veteran housing or healthcare, have got whatever their wants are over the needs of the veterans," he says.

Reynolds helped galvanize a community of homeless vets camping out at the VA's gates in an area known as "veterans row" about three years ago. He says the VA still felt like a place that would always find a way to tell you "no."

"There was no 24-hour shelter. So you have veterans that were showing up in the afternoon being like, 'Hey, I need a place to stay.' And they would tell them, 'Oh no, come back tomorrow or the following day. But you can't stay on the property tonight.' Then they would end up out in the street," says Reynolds.

"They finally build up enough courage to ask for help and then get turned away. You just sever the trust and then it makes it that much harder to get them in the next time," he says.

The vets outside the gates with U.S. flags draped on their tents brought public pressure, and VA brought veterans row inside the campus. It's now a compound of 140 basic huts; six of them — soon to be 12 — are available 24/7 for vets who turn up.

In September, Robert Canas, an Air Force vet who had been on veterans row, moved into a studio apartment in one of the new buildings. Canas had been homeless for about five years.

"I was drinking heavily. Just to fall asleep on the streets I was drinking a lot," he said. "It wasn't till I got here that I got sobered up."

Canas got therapy at the VA and quit drinking about two years ago. His new apartment is subsidized so it only costs him $60 per month. Despite all that, he hasn't completely changed his opinion about the VA.

"What's sad is still finding all the obstacles here at the VA," he says.

Disability miscounted as income

Sitting on the couch in his new place is one example of what Canas means: Army vet Joshua Erickson. He lost a leg to a landmine in Afghanistan and is rated 100% disabled by the VA, which means he makes too much income to get a housing voucher from Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

"On top of my service connected [disability] money, I get Social Security," Erickson says with an uncomprehending pause. "I make too much money."

He's up in Canas' new apartment to use the Wi-Fi and hang out indoors - he's living in a hut on the compound of what used to be veterans row. Erickson says he'd like to go to school and learn to make prostheses like the one he's wearing. He used to have three different prosthetic legs, but the others got lost or stolen while he was on the street.

After Erickson steps out, Canas vents.

"He stepped on a landmine trying to rescue another soldier. I get this beautiful apartment ... and he can't live here," Canas says. "And he even says he feels like he's not wanted here by both the community and the VA. They want you homeless and desperate."

Canas says this while he himself lives in a VA-provided apartment and gets VA care. Officials know the VA has to fix this trust problem.

"We have people who are getting harmed now because they are afraid to get services or they're convinced that the VA is out to get them or is evil," says John Kuhn. He's the deputy medical center director for VA Greater Los Angeles and also the self-described "homelessness guy."

Kuhn is a social worker with 30 years experience on the issue, and he previously led a successful rapid rehousing program at VA.

"I'm asking those veterans to get up and try again. You have a home here. You have an opportunity here to reach out to get the service you are entitled to. We are here. One third of our staff are veterans," says Kuhn.

Kuhn says it's absurd that veterans like Josh Erickson are caught in red tape, that their VA disability is counting as income. The VA has been working with the Treasury Department and HUD to change that, Kuhn says, but it may take action by Congress.

That's hard, but not impossible. Despite Washington gridlock, Congress comes together more often on veterans issues, including the approval of hundreds of millions of dollars for the West LA campus. With the construction finally happening all over campus, Kuhn allows himself some optimism.

"We have the resources, we have the team. There's no reason for any of our veterans in LA to be homeless," he says.

For years now, he says, LA has been housing more vets than any other VA in the country but not keeping up with the number who fall into homelessness.

If this campus can stay on track, Kuhn is hoping to finally get ahead of that curve.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content