Section Branding

Header Content

He disappeared in 1995. His mother's search led to a mass grave and changed laws

Primary Content

This is the sixth story in The Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island series from Radio Diaries. You can listen to the next installment on All Things Considered, and read and listen to previous stories in the series here.

One evening in the fall of 1995, 21-year-old LaMont Dottin didn't come home. He was a freshman at Queens College and was living with relatives, having recently moved to New York from California.

LaMont's mother, Dr. Arnita Fowler — who holds a doctorate in management — was still in California and flew to New York the next day. But when she went to the police to report her son missing, the officer she spoke with was dismissive. Her son was an adult.

"No matter what I said," she remembers, "He says, 'No, take my word for it. He'll be home soon.'"

But LaMont didn't come home, and Fowler kept returning to the precinct. Finally, about a month later, police officially listed him as a missing person. His case was transferred to the Missing Persons Squad, joining thousands of other cases on the docket to be investigated.

Fowler started calling Missing Persons at least twice a week to follow up. "But they would refuse to meet with me, and just say, there's no update, or, we have a new detective on it," she remembers.

This pattern would continue for the next four years.

In the mid-1990s, the NYPD's Missing Persons Squad was "in a state of disrepair," says Phillip Mahony, who joined the squad as a sergeant in 1997. "There was no work being done on cases. Record keeping wasn't good."

Kameron Brown also joined the squad as a detective in 1997, and he remembers Fowler's frequent calls to the office. "I definitely remember [LaMont's] mom being very persistent," he says.

Brown says the caseloads assigned to each detective at the time were overwhelming. He remembers working as one of 10 or 11 detectives, each with between 20 and 40 cases. NYPD records show that, in 1997, the squad was assigned more than 7,000 missing persons cases overall. And resources were tight. According to Mahony and Brown, the squad had no cars that officers could use to conduct investigations.

"I remember looking at this spreadsheet of open missing person cases," Mahony remembers. "It just went on for like a hundred pages because they were never closed."

Mahony says cases of missing adults, like LaMont, would have been low on the squad's list of priorities at the time.

While she was waiting for answers from the police department, Fowler upended her life to look for her son herself. "I was known as a one-woman search party," she says.

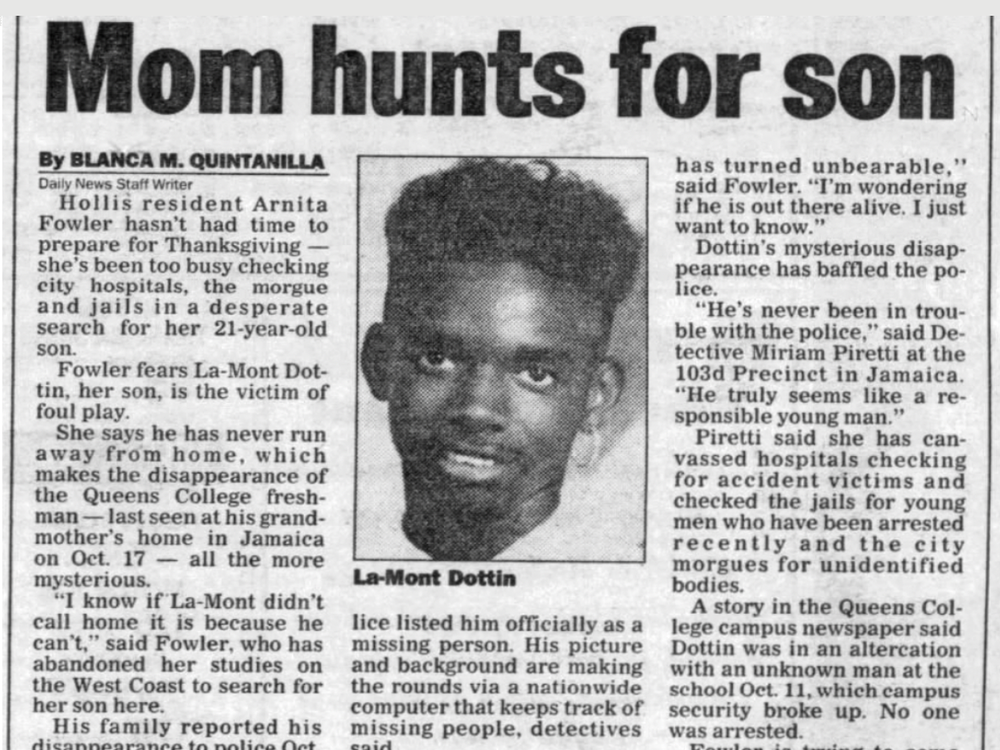

She started writing press releases and holding press conferences to draw attention to her son's case. The story was covered by several local outlets, including the New York Daily News.

"Arnita Fowler hasn't had time to prepare for Thanksgiving," begins one Daily News article from Nov. 1995. "She's been too busy checking city hospitals, the morgue and jails in a desperate search for her 21-year-old son."

LaMont's father, Norman Dottin, who lived on Long Island at the time, remembers distributing flyers and going door-to-door with other family members and friends. "We had no idea where to look," he says.

In an effort to find clues to LaMont's disappearance, Fowler spoke with her son's friends, as well as students and teachers at Queens College. She hired a private detective. "I would look in every homeless person's face as I walked the streets," she remembers.

"I go, was I crazy?" she says, as she thinks back on it now. "But I know that I could not live the rest of my life not knowing if he was out there."

LaMont was Fowler's only child, and she was just 17 when he was born. "We were always together," she says. "And I know he was saying, 'My mom's going to find me.'"

In 1998, Mahony was promoted to commanding officer of the NYPD Missing Persons Squad. He set about implementing a series of reforms, including creating a specialized team to revisit "the hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of active cases that had accumulated over the years," Mahony says.

Brown was assigned to this unit, which came to be known as the Long Term Case Team. Some of the cases they were assigned had been open since the 1950s. They were given cars and other resources to go out and investigate. No matter how much time had passed, Brown remembers, "When you really go back and still speak to parents, that same pain of their child being missing was still there."

LaMont's case was assigned to the Long Term Case Team in March of 1999.

A few months later, Fowler made one of her routine calls to the Missing Persons Squad, and got a different response than usual. "The same man who had been telling me no — it was the same guy!" she remembers. "He said, 'Sure, we'll meet you.'"

When detectives visited Fowler the next day, they told her that LaMont's body had been found in the East River in Oct. 1995, a week after he went missing. His body would have been sent to the morgue, where fingerprints would have been taken and submitted for cross-checks with local and national databases.

But LaMont's body wasn't identified. He became a John Doe, and, like other unidentified New Yorkers, he was buried on Hart Island in a mass grave in early 1996.

When detectives revisited the case in 1999, however, they made a surprising discovery. Just a few weeks after his death, the FBI had actually matched fingerprints taken from a body found floating in the East River with LaMont's fingerprints in a national database. According to Fowler, his fingerprints were in the database because of an arrest for a stolen car when he was in high school in California.

News reports from the time say it was unclear exactly how the breakdown in communication between the NYPD and FBI occurred. Records from the NYPD show that LaMont's body was identified through fingerprints on Sept. 7, 1999. Finally, detectives marked the case closed.

"I couldn't imagine that this was the outcome after four years," Fowler says.

The detectives also shared the news with LaMont's father, who was a city police officer himself. "I probably was pissed off at the time, because you would expect them to be a little more diligent because I was a police officer," Dottin says. "But over the years I've come to accept the fact that — man, they didn't put him where he was at."

LaMont's family never learned exactly how he died. Though Fowler received an autopsy report, she chose not to read it. Instead, she shared it with a relative who told her there was no blunt force trauma, and nothing indicating foul play. She does not believe her son took his own life.

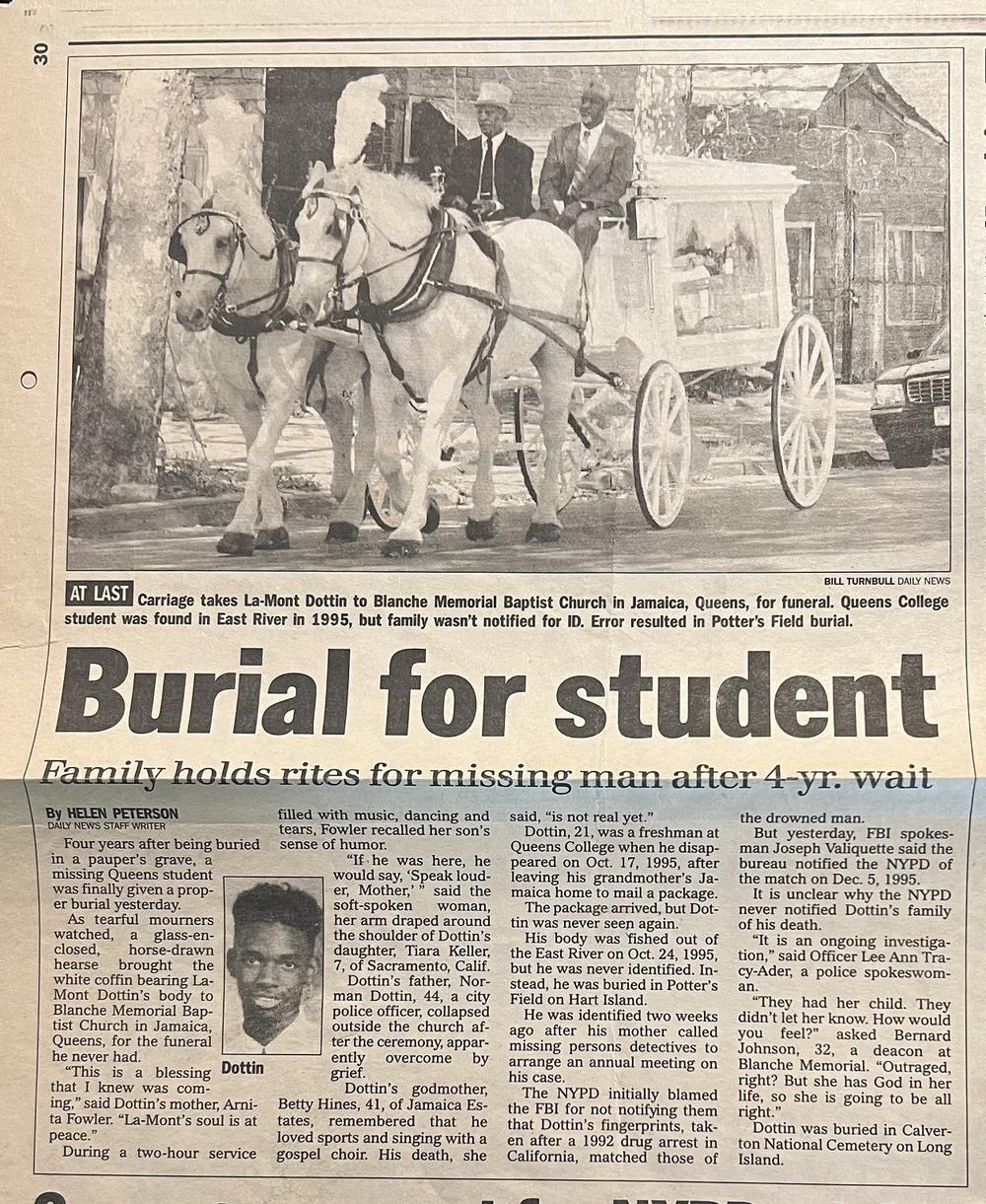

Immediately upon learning LaMont was buried on Hart Island, Fowler decided to have his body exhumed and organized a funeral at Blanche Memorial Baptist Church in Queens. The funeral was covered by the New York Daily News, which featured a photograph of a new, white casket being drawn in a carriage by two white horses.

"It is what I believe that he deserved, nothing but the best," Fowler says. "I needed memories to be something that you could reflect on who he was — the prince that he was to me." LaMont is now buried in Calverton National Cemetery on Long Island.

After her son was found, Fowler became an advocate for missing persons and their families and began pushing for reforms to New York's missing persons laws. In 2016, New York State passed LaMont Dottin's Law, which requires police to expedite searches for missing adults by reporting them to the National Crime Information Center database. Previously, such reports were required only for missing children, and adults who were considered vulnerable.

More recently, Fowler has advocated for similar requirements at the national level.

New York City has also seen improvements in the identification of John Does in recent years, including through the use of DNA technology, which has helped identify a number of previously unnamed bodies buried on Hart Island.

In spite of the decades that have passed since LaMont's disappearance, Fowler says she still misses him every day. "I can, as a mother, still smell what he smelled like, still hear what he laughed like," she says.

"People just don't disappear."

New York City's Parks Department, which has managed Hart Island since 2021, has announced that it will begin offering public tours of the cemetery for the first time this week. For more information visit https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/hart-island.

This story was produced by Alissa Escarce of Radio Diaries. It was edited by Deborah George, Joe Richman, and Ben Shapiro. Thanks also to Nellie Gilles, Mycah Hazel and Lena Engelstein of Radio Diaries.

This story is the sixth in a series called The Unmarked Graveyard: Stories from Hart Island. You can find other stories from Hart Island on the Radio Diaries podcast.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.