Caption

Over 100 people filled a conference room at Macon's Elaine Lucas Senior Center Monday to learn more about the special session of the Georgia General Assembly.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB

The special session of the Georgia General Assembly beginning this week presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity for Black people in what was once the heart of the plantation South to wrest political power from white politicians who ignore their needs.

That was the message from elected officials and others in a community meeting of about 100 people at the Elaine Lucas Senior Center in Macon Monday.

“They want to make sure that Black people can't control this region — period,” said Georgia House Rep. and minority leader James Beverly.

“They” are the Republicans who, because the GOP holds in the majority in both houses of the Georgia Legislature, will control the drawing of new legislative district lines during the special session.

That fact is in tension with the reason for the special session in the first place.

Over 100 people filled a conference room at Macon's Elaine Lucas Senior Center Monday to learn more about the special session of the Georgia General Assembly.

In October, Federal Judge Steven C. Jones published an opinion in which he agreed with plaintiffs who said current Georgia legislative maps do not adequately represent Black communities, mostly across what is known as the Black Belt.

“That is the belt all across the middle of the state,” explained Fenika Miller of the group Black Voters Matter. “It had the highest population of enslaved people. And now you have a large and high concentration of Black people who still reside in these communities.”

That includes Macon, and, Miller said, it’s where the problems which disproportionately affect Black people are easiest to see.

“Medicaid expansion; housing; Black women are some of the highest rates of folks to lose their housing,” Miller said. “The cost of living is increasing. Everything is going up except for our salaries.”

Meanwhile, she said, the state’s current slate of political leaders have a hefty budget surplus which she hopes newly elected leaders might try to free up.

“What would it look like to have a person in that seat to advocate for us to make sure that those rainy-day resources that our communities and our households need can access those?” she asked.

Fenika Miller, member of Black Voters Matter, speaks during a November 2023 community meeting in Macon ahead of a special session of the Legislature to redraw the state's political maps.

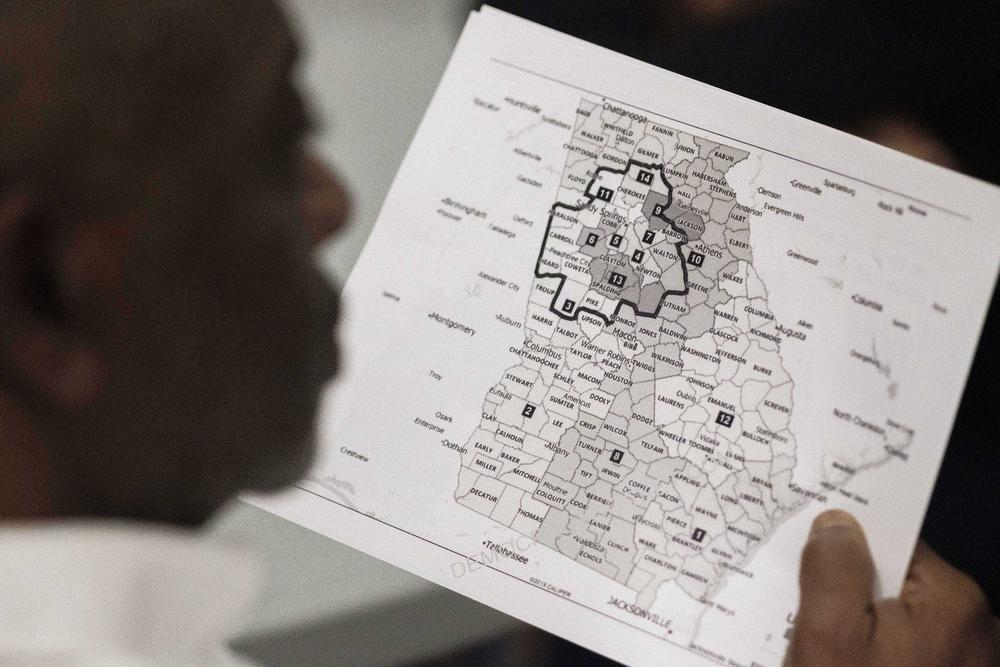

To help imagine what that might look like, and how the special redistricting process could make it so, Miller, Beverly and State Sen. David Lucas walked the group through legislative maps as they could come together, starting with the maps Jones agreed in his decision would hit the mark.

But Beverly, Miller and Lucas agreed it was almost guaranteed that at least the first maps proffered during the special session would not look like the maps published in the judge’s opinion.

When the first draft of new House district maps came out a day later, they were proven right. In the map which the federal judge said reached equity, House District 149 is anchored by East Macon, which is majority Black, and extends through rural Twiggs County and Wilkinson County, both nearly 40% Black, thereby concentrating Black voting power. In the first new map published by the Georgia House, Twiggs and Wilkinson are balanced against majority white Bleckley County and Dodge County in House District 133, likely diluting Black representation.

In short, the House version draws Twiggs and Wilkinson into a majority white House district. The judge's map does the opposite. County commissioners and mayors from both counties attended the Macon meeting.

“Everything you’re going to see from this point forward is going to be so that white folks maintain power in the Black Belt — everything you see,” Beverly said. “The reason why we're here is because we need to come up to the capital city and say ‘We refuse to have that happen, especially the Middle Georgia area.’”

Two of the five new Georgia house districts described in the court opinion start in Macon. That’s why Miller said Black Voters Matter is ready to take people from Middle Georgia to the Capitol for the duration of the special session, and for those people to make it clear if new maps don’t measure up.

“And we hope that even if the Republicans come back with a map that we don't like, with shenanigans, that it goes back in the same vein as it did in Alabama,” Miller said.

In Alabama, a court-appointed special master was given the job of drawing fair district lines after a federal court said state legislators there didn’t get it done.

A proposed map of new state Senate districts.

Beverly said ongoing, coordinated feedback from everyday people could be crucial to similarly steering the Georgia process as the judge, whom Beverly described as the backstop of the process, reviews the new map the General Assembly sends for review.

“We need that on the record,” Beverly said. “And so if you put that on the record, when the map goes back to the judge, then we can say, [Sen.] Lucas can say, I can say as a leader, the plaintiffs can say, Fenika can say, ‘Hey, we had people come up. We want representation.’”

And the cycle might begin anew with the judge asking legislators to draw new lines until they land on something he approves.

Once the process was explained, the microphone left the dais and was handed around the room. Shekita Maxwell of Macon’s Unionville neighborhood grabbed the opportunity to pull the conversation away from the abstraction of district lines and coded maps and back to the day-to-day.

“They put storage units all over Unionville, they’re kicking us out of our houses saying that we don't belong here,” Maxwell said.

Unionville was a neighborhood where during the Great Depression, the federal government told banks not to engage in mortgage lending, a mapping process called “redlining.”

But Maxwell, broadly, was over maps.

“So when are we going to say that we are the map?” she asked. “We're not just drawing lines. If Macon is the heart of Georgia, when are we going to get it straight?”

The special session of the General Assembly for redrawing the state’s legislative maps is expected to last at least through the first week of December.