Caption

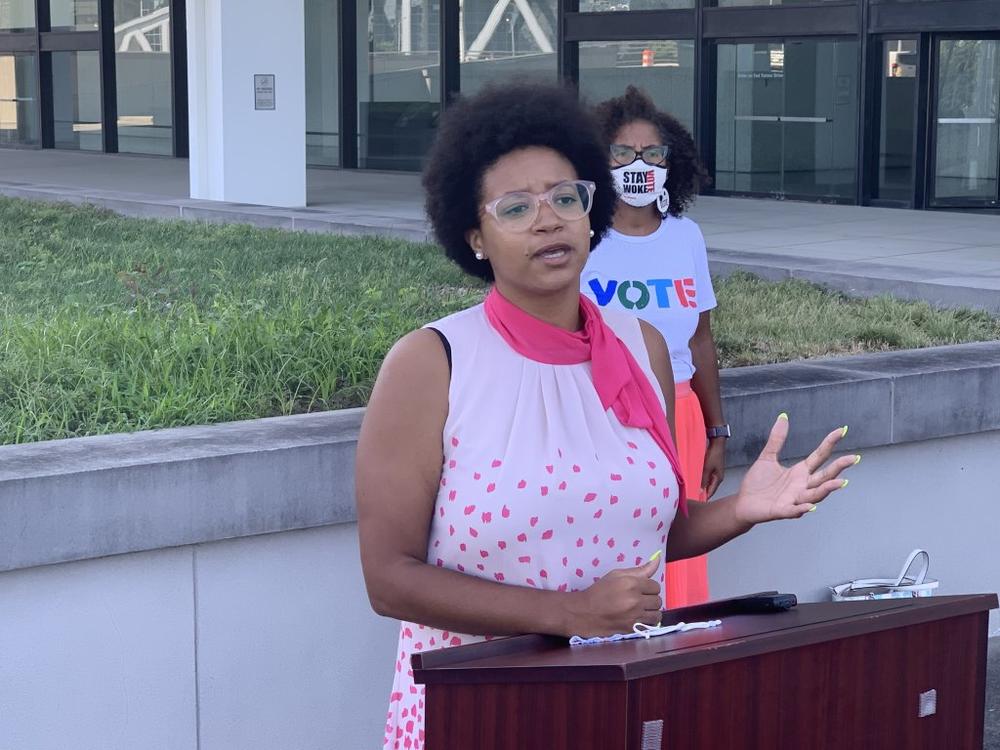

Brionté McCorkle and three other Black voters from Fulton County have filed a motion to stay an appellate court’s ruling. Filed Dec. 7, the motion asks the appeals court to halt the effects of its own decision while the plaintiffs “ask the Supreme Court to clarify the important issues in this case.”

Credit: Stanley Dunlap/Georgia Recorder