Caption

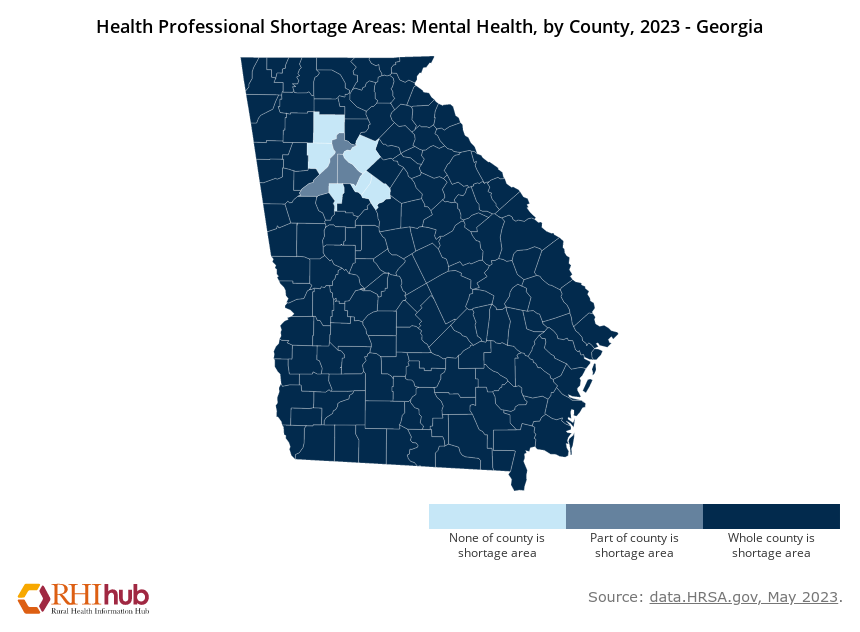

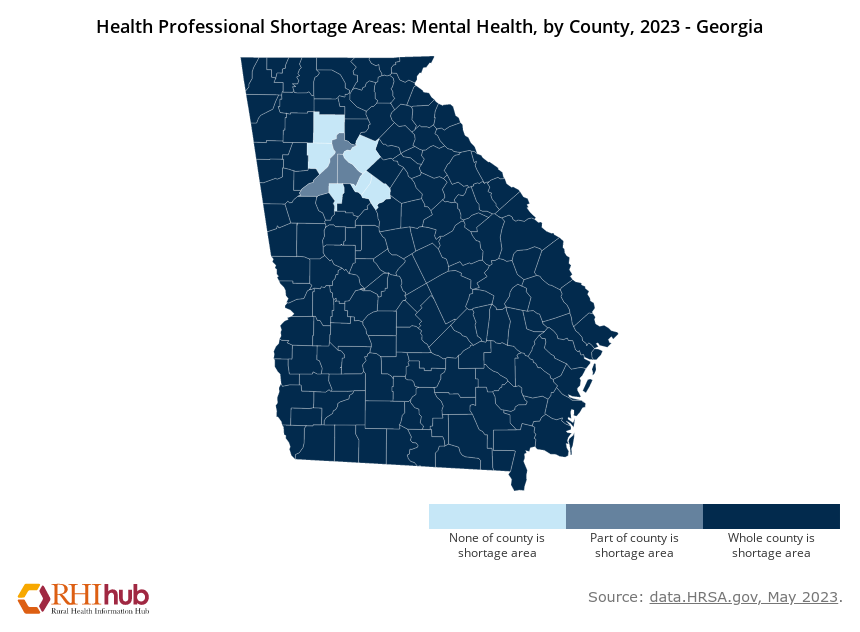

Most of Georgia' 159 counties struggle with a shortage of mental health providers, according to the Rural Health Information Hub.

|Updated: January 8, 2024 8:04 PM

LISTEN: Only six of Georgia’s 159 counties have enough mental health care professionals. A new study published in the journal Nature Mental Health shows people with limited access to mental health care resources also have less access to mental telehealth. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge reports.

Most of Georgia' 159 counties struggle with a shortage of mental health providers, according to the Rural Health Information Hub.

When people in rural counties can't connect to local mental health care services in their community, telehealth care can help. But these are also the counties most likely to lack access to broadband, according to a national study published Jan. 4 in the journal Nature Mental Health.

The study defines counties with low broadband access as those in which the percentage of households without broadband was greater than the national median of 26.5%, and counties with high broadband access were defined as those in which the percentage of households without broadband was less than the national median.

The inability to afford broadband, or high-speed internet, is critical since everyday activities increasingly occur online, yet barriers to access for some contributes to the gap between those with and without access, known as the “digital divide.”

Rural areas of the nation are especially hard hit.

Most of Georgia — 151 of 159 counties — struggles with a shortage of mental health providers, according to the Rural Health Information Hub. Only six metro Atlanta counties have no shortages, but Fulton and DeKalb have shortages in parts of the counties.

Poverty has also been linked to a higher rate of mental illness. Children in the poorest households have a threefold increase in the risk of having a mental illness compared with children in the wealthiest households, said study coauthor, Khushi Kohli.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed existing problems in the health care system that have been creating disparities.

Suicide rates in rural counties are twice that of urban counties, and issues like anxiety, social isolation, depression, and the whole spectrum of mental health disorders are exacerbated, Kohli said.

A big hope that emerged out of COVID in the aftermath was that health care would be considered a right for all, coauthor Bhav Jain said.

"Even though health care is easily accessible among people who have access to internet or who are in urban areas, if anything, the disparities are only going to increase among those who are in rural areas," Jain said. "And so it's actually a question as to is health care a right for all? What sorts of infrastructural investments is our nation making to ensure that the people of Georgia have the same access to health care as every other state?"

Georgia has long ranked at the bottom of the nation when it comes to access to mental health care, and Mental Health America ranked the state 49th in 2023.

But many public and private organizations are working to close the gaps.

Many practices are transitioning to more telehealth care, but Dr. Lateefah Watford, a psychiatrist with Kaiser Permanente in Georgia, said that providers were already doing more virtual consultation.

"Once the pandemic hit, it became almost essential that we provide digital care," she said. "And what we have learned is that, treatment wise, it can be as appropriate and as useful as face to face."

Part of the problem leading to increased demand for services is that a lot of students' development is peer- and group-based, Watford said.

"We are seeing increased anxiety now," she said. "Does this mean that the number is just exponentially increased and that's what we're seeing? Does it mean that we are identifying sooner? Does it mean that children are now speaking on it more? I think all three are actually truthful."

Shriya Garg graduates Rome High School. Now a student at the University of Georgia, Garg saw firsthand the effect of lack of internet access on her classmates in Floyd County.

Shriya Garg started Rome High School in Georgia's Floyd County the year COVID-19 disrupted everyone's lives.

Her research now as a first-year student at the University of Georgia in Athens is informed by her personal experience.

"When I was in high school, there were students in my grade that didn't have internet," Garg said. "They couldn't get on Google Classroom at home. They couldn't access Khan Academy or educational resources. And, you know, this impedes them in a future sense, if they can't get the basic high school education that, you know, every student is guaranteed."

In Rome, Ga., 18% of households are not connected to broadband. In Athens, where she lives currently, 23% of households are not connected to broadband, Garg said, nothing these aren't even the worst areas.

The internet is increasingly critical for everyday life, but the cost to access broadband — high-speed internet — may keep some people from it.

To make it more affordable for low-income Americans, the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) is a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) benefit program that helps ensure that households can afford the broadband they need for work, school, health care, and more.

The program provides a discount of up to $30 per month toward internet-service-eligible households. Eligible households can also receive a one-time discount of up to $100 to purchase a laptop, desktop computer, or tablet from participating providers if they contribute more than $10 and less than $50 toward the purchase price.

As of September 2022, over 14 million households had enrolled, which is about a third of the estimated eligible households.

The FCC reimburses participating internet service providers for providing discounts that allow people to pay $30 per month.

(Left to right) Bhav Jain with Stanford Medical School, Khushi Kohli with Harvard, and Tej Patel with the University of Pennsylvania.

The program has the ability to give people all the infrastructure they need, essentially, to create telehealth appointments, said study coauthor Tej Patel.

He said it's worth working with legislators within Georgia and other states that have low uptake of the ACP to increase awareness of the benefit.

"I think that's a common solution for how we can kind of bridge these divides between different populations," Patel said.

Over the past two years, Gov. Brian Kemp distributed $642 million in federal COVID-19 relief money to fund internet expansion projects in rural Georgia. Investments and the projects associated aimed to serve roughly 200,000 of the remaining 455,000 unserved locations in the state, the governor's office said last year.

The state of Georgia received $4.8 billion in federal funding as part of the COVID-19 relief package congressional Democrats approved in March 2021 and must spend it by 2024.