Section Branding

Header Content

Could lab-grown rhino horns stop poaching? Why we may never know

Primary Content

Late at night in his dorm room, Huyen Hoang was about to fall asleep when he could not shake off what he saw — a photo of a rhinoceros dead and dehorned in Vietnam.

It was 2011 when Hoang, a Vietnamese American, first learned about rhino horn poaching. That same year, the Javan rhino was deemed extinct in his home country, and rhinos elsewhere were being hunted at record pace.

Hoang was 21 and a business major at Portland State University at the time. His twin brother, also named Huyen Hoang, was working part time at a biotech lab. One night while visiting home, the two brothers hatched an idea: What if they could curb poaching by giving rhino horn buyers another option?

"We both wanted to do something new and courageous, something meaningful," said Hoang, the business major.

In their senior year, the Hoang brothers founded Rhinoceros Horn LLC, which sought to make and sell a lab-grown version of the chief ingredient found in rhino horns — keratin. But they weren't alone. That same year, a startup named Ceratotech entered the fray with intentions of growing life-size rhino horns using the species' stem cells. In 2015 came a third company, Pembient, a biotech firm devoted to reprogramming yeast cells to produce rhino horn proteins.

The attempt to solve an age-old problem through new technology captured the imagination of people across the world. The idea was catapulted into a media frenzy. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were invested, labs across the United States were involved and stockpiles of prototypes were made.

But nearly a decade later, the industry is hanging on by a thread. Rhinoceros Horn LLC stopped operations in 2016. Pembient is expected to shut down this year. Ceratotech remains active but is struggling to find funding to advance its research.

Even if the companies survive, they would still have to confront growing scrutiny of biofabricated products of endangered species from the more than 180 nations that are parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. The treaty, known as CITES, is meant to ensure that the survival of endangered species is not jeopardized by global trade.

So what happened? In interviews, the founders of all three companies said that trying to disrupt the illegal market for rhino horns through the introduction of an engineered alternative was a goal without precedent — one that presented financial, logistical and legal challenges alike.

For their plans to work, long-standing beliefs around how best to protect an endangered species would have to be shaken. That quandary put them at odds with an unexpected source — the very groups devoted to protecting the rhinos.

"They saw us as undoing the work that they've been doing and the programs that they've had going," Hoang said. "So there was just no room for us in their work and their solution."

Conservationists interviewed for this story say there was good reason for the resistance, describing the companies' efforts as misguided at best and dangerous at worst.

"If you want us to experiment on this technology, do it with another species that's not going to be wiped out within five years if it goes wrong," said John Baker, the chief program officer of the conservation group WildAid. "You have no room for error."

Fewer than 27,000 rhinos are left in the world

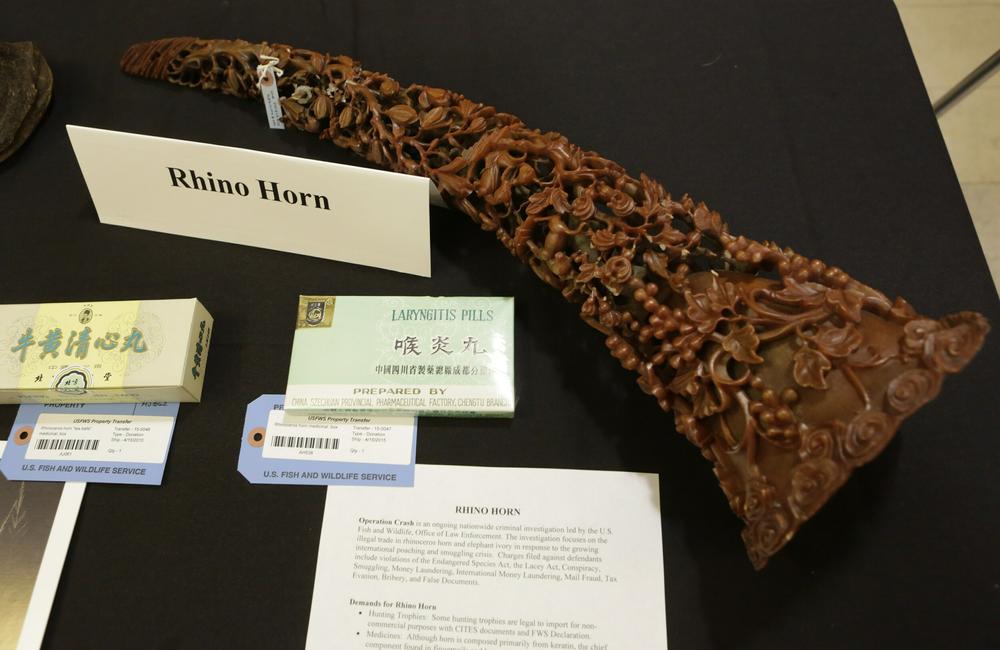

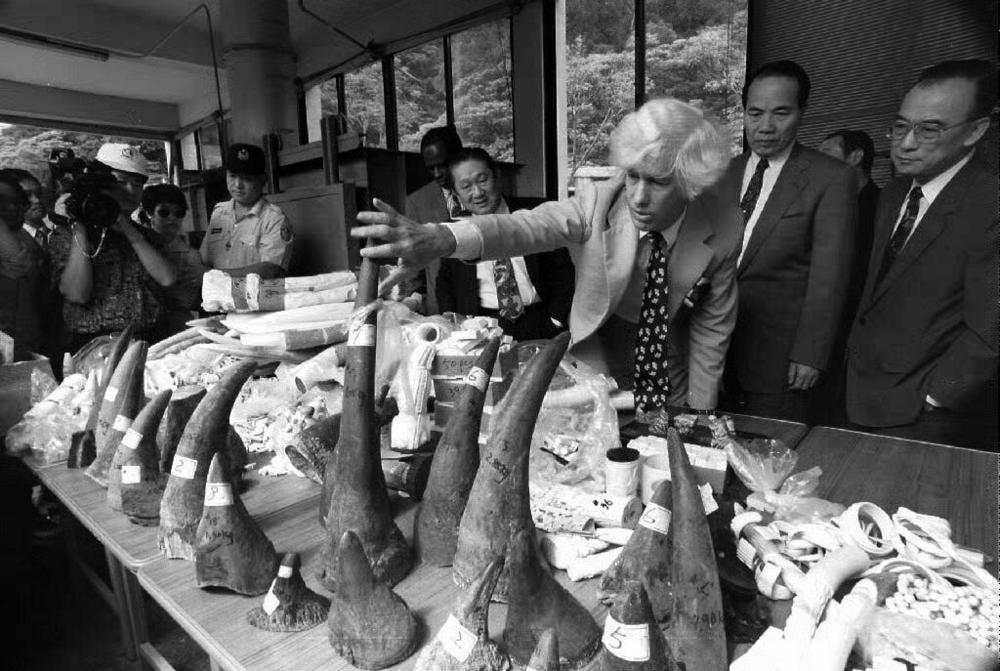

Rhino horns are among the most valuable products in the wildlife black market. The appendages have been sold for as high as $400,000 per kilogram — or about $11,000 an ounce — outpacing the cost of elephant ivory and gold.

The top rhino horn markets are in China and Vietnam, largely driven by the wealthy. Considered a status symbol, horns are carved into luxury items like art, jewelry and decor. While a shrinking number of consumers believe horn shavings can treat certain cancers or hangovers, there is no evidence to show that keratin, the same protein found in human hair and fingernails, has such benefits.

At the start of the 20th century, there were about 500,000 rhinos around the world, according to the World Wildlife Fund. But habitat loss and poaching led to a staggering population decline.

To protect the species, international trade of rhino horn was outlawed under CITES in 1977. Soon after, a sophisticated international poaching industry emerged to hunt for horns, involving everything from helicopters to night vision gear to silenced rifles.

As of 2022, about 27,000 rhinos were left in the world and at least 561 were killed in Africa, according to Save the Rhino International.

A cold reception

The idea for lab-grown rhino horns emerged at a time when genetic engineering, from cultured meat to milk, was an increasingly popular and expanding industry.

Pembient CEO Matthew Markus launched his company on the belief that such technology did not have to be confined to livestock. Rather, it could be a force for good for endangered species too.

Markus said that in the early days of his startup, he sensed some skepticism from the conservation field but that all in all, he did not anticipate it to be a nonstarter.

"I didn't think it would backfire or it would be a game-stopping issue," he said. "I expected negative feedback and maybe through a series of dialogue, we would come to some sort of agreement over time."

Early complaints centered on his initial idea of producing synthetic rhino horn powder. Some conservationists feared that the product would give credence to the false belief that horn shavings have medicinal value. So, Markus said he pivoted his focus to the carving market and creating solid horn.

But he continued to meet resistance.

His plan was to flood the market with lab-grown horns in the hope of diluting the value of the real thing. But many conservationists argued that producing engineered horns would only increase demand for authentic horns.

Worse, his critics said, it could create new uses, alluding to past comments by Markus about the possibility of using his product to make items like iPhone cases and engineered-horn-infused beer. There were also fears that bio-identical horns would only make it harder for law enforcement to police the smuggling of real horn.

Two sides at fundamental odds

Engineered rhino horns, to many conservationists, were not only an absurd idea from a technological and business standpoint. Some feared that the venture could also undermine conservation efforts — work that took decades.

Wildlife groups have devoted years to debunking medical myths and raising awareness of rhino slaughter in hopes of reducing demand. But the startups believed demand did not have to be a threat if a sustainable alternative could be there to meet it.

"By promoting synthetic rhino horn products, the main message to society will be that it is acceptable to use rhino horn, because most consumers likely won't really understand the distinction," said Baker of WildAid.

Some conservationists point to the one-time legal sale of elephant ivory in China and Japan in 2008, which studies show triggered an increase in illegal ivory trade.

The two sides also held opposing views over whether rhinos could afford exposure to any additional risk.

An underlying philosophy in conservation is the precautionary principle — the belief that a strategy's or product's risks should be greatly mitigated before moving forward. That approach suggests endangered species should be cared for with methods that are tried-and-true.

Baker gave the example of Taiwan, which in the 1980s was once Asia's biggest consumer of rhino horns. Today, demand in Taiwan is nearly zero thanks to a combination of international pressure, local law enforcement and a national campaign debunking myths about rhino horns' supposed medicinal value.

"We know it can work and it takes time," Baker said, noting that poaching has declined significantly in recent years. That has helped the population of at least two species, the black rhino and the greater one-horned rhino, bounce back.

Other conservationists also took issue with the for-profit model. Tanya Sanerib, the international legal director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said those attempts affirm the idea that "wildlife has to pay its way to stay."

"Trying to commercialize and commodify wildlife in some manner as a way of benefiting it and conserving it is the wrong approach," Sanerib said.

The pushback

In 2016, the debate came to a head when several wildlife groups urged the U.S. to ban the sale and export of lab-grown rhino horn.

"Despite near-universal condemnation by conservation experts, the serial entrepreneurs peddling this product are playing a dangerous game for their own profit, while conveniently overlooking the genuine threat it poses for rhinos," Peter Knights, then the head of WildAid, said in the petition.

The federal government ultimately deferred the request to CITES, but Pembient's Markus said the ordeal drove away potential investors and collaborators.

"It just seemed we had a policy disagreement, but instead of arguing about policy, they just assumed their policy is right," he said.

Then in 2018, Pembient was hit with a pair of investigations from Washington state, including an audit, spurred by the Humane Society of the United States and Humane Society International, a family of organizations focused on animal protection.

They alleged Pembient was planning to illegally sell lab-grown horn made from biological materials derived from rhinos, according to documents shared with NPR by the two Humane Society groups. Markus told state authorities that his company was still in the design phase and had plans to use cow stem cells if rhino cells were not allowed.

Neither inquiry resulted in any charges or fines, but Markus said they delayed Pembient's progress for several months.

In a statement, Humane Society International's senior vice president of programs and policy, Anna Frostic, said the organization acted in the best interest of rhinos.

"The Humane Society family of organizations is unwavering in its commitment to ensure that state and federal wildlife protection laws are strictly enforced," Frostic said.

While Pembient received arguably the fiercest opposition to its idea, the founders of Rhinoceros Horn LLC and Ceratotech say their companies were similarly affected by a lack of support from wildlife groups.

"We were continuously being classified as troublemakers or people who were greedy capitalists," Hoang said. "And we just didn't have the platform to defend ourselves."

After college, the Hoang brothers struggled to convince merchants that their synthetic horn powder trumped the real thing, despite arguing that their product was better for the environment and engineered to have legitimate health benefits.

The brothers believed the solution was to partner with wildlife groups, which had years of experience working to sway the behavior of rhino horn consumers. But Hoang said the conservationists he spoke to were adamant that his product would hurt, not help, rhinos.

At Ceratotech, CEO Garrett Vygantas said one of the early challenges at his company was retrieving cells from a rhino. He hoped to collaborate with a zoo, but Vygantas said it was clear zoos did not want to get involved without the support of conservationists. It took about a year to obtain rhino cells through the private sector, according to Vygantas.

"I don't blame them," he said. "I could see how introducing a lab-grown horn could be a threat to that vision. The question is, has it worked?"

Unanswered questions

Despite all the years of debate, there is still little research on the effects of engineered rhino horns.

Fred Chen, an economics professor at Wake Forest University, has formulated economic models to predict how lab-grown horns would do in the market. His research suggests that engineered horns could be a powerful tool in conservation even if they led to some increase in the demand for the real thing.

"You can't just say, 'Oh, it could lead to more demand, so we don't want it.' I think we need to dig a little deeper than that," he said.

Meanwhile, Hoai Nam Dang Vu, a researcher at the University of Iceland, said he is less optimistic about lab-grown horns because of the strong demand for real horn. In interviews with over 1,000 rhino horn consumers, he found that some buyers are willing to go as far as buying DNA tests to ensure their purchase is legitimate.

Both Dang Vu and Chen support more research and real-life experiments to test the theories around bio-identical horns.

"I have seen a lot of arguments from both proponents and opponents of a legal trade of rhino horn or the introduction of biosynthetic horn," Dang Vu said. "But none of these initiatives have been materialized. So I think it's time for us to do something rather than keep talking."

That could prove difficult. In 2022, members of the CITES treaty voted to regulate biotech products in the same manner as the endangered specimens they are designed to mimic. There are still ongoing discussions at CITES on how to implement the decision, but for rhino horn, whether real or fabricated, a commercial trade ban applies.

Today, there are only a few real-world examples of what happens when a synthetic product is brought into a market to help protect an endangered or threatened species.

About a decade ago, over 800 leopards were killed each year in South Africa for their fur. Part of the demand stemmed from members of the country's Shembe Church, who wore the pelts as ceremonial garb. But in 2013, the Shembe Church started replacing their leopard fur coats with synthetic ones in an effort to protect the wild cat.

That was made possible only through a partnership among wildlife group Panthera, faux-fur designers and the local church leadership. Within a few years, authentic leopard fur use was cut in half and thousands of leopard deaths were prevented, according to Panthera.

What comes next

At the heart of most wildlife challenges are questions of human behavior, needs and motives. How do you get consumers in Vietnam and China to challenge their generational beliefs around rhino horns? How do you persuade poachers in South Africa to stop, especially if there are no other job options? And how do you spur people to care about a species that's a continent away and far from plain view, enough to get them to make new decisions?

The companies that set out to reshape the conservation landscape believed technology might offer a way to fast-track these sorts of changes. More than a decade later, that once lofty goal largely remains an untested theory.

Vygantas, of Ceratotech, said his lab would be a year or two away from producing a life-size engineered horn if it had sufficient funding. He added that lab-grown horns will never be successful without conservationists' support. Until then, lab-grown horns will always be treated as some kind of "contraband," he said.

Markus continued to try to rally support from stakeholders beyond the conservation community. In 2016, he spent months in South Africa attempting to form partnerships with national parks, but officials voiced the same concerns as conservationists, according to an upcoming documentary, Horn Maker, about Markus' yearslong efforts at Pembient.

His company generally stopped its operations after COVID-19 hit. Since then, Markus has found other work. So far, Pembient has not been able to successfully produce a life-size horn.

"I think it's dangerous to say this was a bad idea or this failed. That was never proved," he said. "We should acknowledge now that these conversations should and will come up in the future."

The Hoang brothers admit they never threw away the first samples of their product. Inside their garage is a stack of boxes filled with powdered keratin — never opened. Similarly, the brothers have yet to file the paperwork to officially dissolve their company, in hopes that one day, attitudes around lab-grown horn may change.

"I learned it's not easy to try to make the world better," he said. "The question as to why that is, everyone needs to find that answer on their own."

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content