Caption

A bulkhead runs along the bank of the Intracoastal Waterway near the Causton Bluff Bridge.

Credit: Justin Taylor / The Current

A bulkhead runs along the bank of the Intracoastal Waterway near the Causton Bluff Bridge.

The public has until Friday, Jan. 19, to submit written comments to a new proposal to change the amount of buffer homeowners must leave between coastal marsh and upland. It would limit buffers to commercial developments and relax them for others.

DNR’s Coastal Resources Division rules currently leave a 50 feet wide buffer. A final vote on the proposed rule is scheduled for 9 a.m. on Feb. 27 at Georgia DNR’s Atlanta headquarters.

Environmental groups are calling on the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to create a stakeholder group before taking final action on the proposed rule change, which they say could damage Georgia’s fragile marshlands.

During a public hearing Jan. 4 at DNR’s Coastal Resources Division (CRD) in Brunswick, representatives of several Riverkeepers organizations, the Southern Environmental Law Center, One Hundred Miles, and others voiced their concerns about the proposed change to the permitting process.

Video of full DNR public hearing

The buffer rule is designed to keep permanent construction projects from damaging the marsh, which is nature’s safety zone between the ocean and dry land. That means no land or vegetation can be disturbed within that 50-foot zone, in an effort to avoid damage during and after construction that could send stormwater runoff and pollutants into the marsh.

Man-made structures, particularly those that “do not provide functionality of and/or…permanent access to the marshlands component” of a project, are forbidden in the 50-foot- buffer zone. In addition, property owners are responsible for managing discharge and avoiding new impervious surfaces in the zone.

Changing the rule would erase the existing 50-foot buffer between high tide lines and “elements of a proposed project” required under Georgia’s Coastal Marshlands Protection Act (CMPA) for residential and municipal infrastructure projects, which make up most of the projects that fall under the rule, according to DNR.

Bigger commercial projects, like marinas, community docks, and commercial docks, still would have to meet the 50-foot buffer requirement.

In a background document on the rule change , DNR says the way the existing rule as worded “creates a burden” for homeowners and municipalities, and makes more work for DNR, which has to sign off on all those smaller projects: “This is particularly burdensome when the regulations, specifically buffer requirements extending into homes, decks/patios, pools, sheds, swing sets, fire pits and other common appurtenances that are not related to the marshlands component, typically a bank stabilization structure (bulkhead, living shoreline, riprap).”

Jill Andrews with the Coastal Resource Division presents possible changes to the regulations on marsh buffer zones. Credit: Justin Taylor/The Current

But environmental groups say that’s the whole point of the 50-foot rule: to ensure that no one damages the marsh and to make sure that DNR enforces protection in that buffer zone.

The proposed rule change would allow multiple homeowners and municipalities to add bulkheads, riprap, or “living shorelines” to protect their property lines. Critics say bulkheads can eat away at the marshland, that local governments lack the expertise to manage shorelines properly, and that all those little projects aimed at protecting individual homeowners’ backyards could add up to major marshland damage.

Other rules prevent homeowners from using bulkheads or other shore-hardening techniques to backfill and extend their land into the marsh, prohibitions which DNR says would not be affected by this rule change.

Groups opposing the proposed change include SELC, Altamaha Riverkeeper, Savannah Riverkeeper, Ogeechee Riverkeeper, St. Mary’s Riverkeeper, Georgia Interfaith Power and Light, Glynn Environmental Coalition, 100 Miles, Center for a Sustainable Coast, and Environment Georgia.

A bulkhead at a private residence on Talahi Island.

Because most bank stabilization projects are small ones taking place on residential property, DNR’s Coastal Resources Division Chief of Coastal Management Jill Andrews said, “we find that the definition of ‘upland component’ in particular does not really clearly apply to bank stabilization projects.”

“Upland” means land that is neither coastal marsh nor wetlands under state rules and regulations. Any parts of those projects that go into the marsh, “including but not limited to marinas, community docks, bridges, piers, and bulkheads,” require a separate permit under the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act.

However, the current rule does not limit that 50-foot buffer to commercial projects only. That can pose a problem for any homeowner whose 50-foot buffer runs under or includes their backyard swimming pool, firepit, or even their house.

Three exceptions to the 50-foot rule include:

DNR says that, in 2007, the original intent of the Upland Stakeholder Committee rule was to limit marinas, community docks, and commercial docks. That 22-member committee consisted of nine developers, nine current and former government officials, and representatives of four environmental groups, and was formed to address rampant development along Georgia’s coastline.

Before August 2022, “only very few shoreline stabilization projects actually triggered the requirement for a CMPA permit,” Andrews explained. Those that did “would have been our larger shoreline stabilization projects greater than 500 feet or ones that were more wholly in the marsh and required fill in marsh.” All those projects were signed off on by CRD and did not fall under the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act (CMPA).

In August 2022, Andrews said, “we revised our practice of how we authorize these type of projects, in order to require that all shoreline stabilization projects get a full CMPA permit. So there’s currently more regulatory oversight of bulkheads and living shorelines now than prior to August 2022.”

Now, DNR wants to limit that permitting to larger projects only.

Opponents of the rule change expressed concern that making such an exception to the existing rule would open the floodgates to more property owners seeking to put in bulkheads. One neighbor said she chose to let native vegetation grow to prevent erosion.

Bill Sapp, attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

At the public hearing on the rule change, SELC Senior Attorney Bill Sapp said, “This all goes back to 2007 when the Coastal Resources Division was faced with a question and that question was, do they have to have a buffer on the uplands right next to a CRD project?” At that time, Sapp explained, CRD put together a stakeholder committee: “They had local governments, they had developers, they had the public, they had environmental groups. And they all worked to address this issue of what a buffer would look like. And again, this is a buffer that is designed to protect the marsh. And we’ve gotten more marsh probably than any other state on the East Coast.

“The work was very messy,” Sapp acknowledged. “Everybody didn’t get everything they wanted. But that stakeholder work served as the basis for these upland rules.”

Alice Miller Keyes of 100 Miles explained why the buffer zone rule should not be changed and asked that a new stakeholder committee be created before the board votes on the proposed rule.

Alice Keyes of One Hundred Miles.

“Coastal Georgia’s marshes are our signature landscape,” Keyes said. “And they’re nature’s sponges. They absorb floodwater and dampen storm surge and filter pollutants. And the area behind the buffer, or upland of our marshes, is just as important as the marshes themselves. These transition zones are known as the buffers….and they’re critical to reducing the damage to the marsh function and to protecting the buildings and the developments within the uplands.”

She added that “living shoreline” reinforcement, which she called “a great example of a method of shoring up property and enhancing the function of the marsh,” as opposed to bulkheads, which “function extremely differently by design. They’re a method to harden or armor the natural transition area, and by definition are designed to separate land and sea, eliminating the function of that natural area.” She quoted from a CRD document that read in part, “Broad scientific consensus is that armoring degrades the integrity of the marine environment.”

Two different agencies handle two different buffer zones, Keyes later explained to The Current. The 50-foot buffer is CRD’s responsibility, and falls under the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act. A separate 25-foot buffer is the Georgia Environmental Protection Division’s responsibility to enforce under the Erosion and Sediment Control Act, which in 2015 was updated to cover marshlands specifically.

“If anything, CRD should retain the responsibility to manage and regulate activities within the 25-foot buffer behind our marshes, because of the critical functionality of that buffer,” she said.

Keyes noted that, when a project overlaps both agencies’ permitting processes, EPD’s only job “is to issue a variance for any erosion and sedimentation control activities within that 25-foot buffer. So basically, if they get a CRD permit, there’s no erosion sedimentation control responsibility.”

In addition, Keyes said, EPD follows erosion and sedimentation guidelines set by the Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission, which is about best-management practices for keeping soil runoff out of the state’s waters. “There are no conditions appropriate for coastal environment,” she said, “and they’re certainly not appropriate for marsh impacts.”

Keyes added that joint permitting with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “no longer seems to apply. There’s a lot of confusion about who do you go to for activities not only within the marsh itself based on size, but also within the buffer.”

She asked for a stakeholder committee “because that extensive engagement is the only way that we’re going to have assurance that our marshes are protected for the long haul, for this generation and for the next, including those property owners who will be impacted by activities that happen next door to them and even further downstream.

Dave Kyler, Director of the Center For A Sustainable Coast.

David Kyler of the Center for a Sustainable Coast said he was concerned that the proposal misses the bigger picture, and requested that DNR “make more information available to the public, rather than on a case-by-case, permit-by-permit basis, on a watershed or year-by-year basis to get an idea of the cumulative effects of multiple permit activities.”

Kyler said he had tried to find that information “by looking at the online CRD permanent database. But from what I can tell in my quick scrutiny of it, it was very hard to initiate an inquiry and what injuries you’re asking for site specific and time specific for one permit.” He said it would be very hard for a member of the public to use that online database “to find out, say in the last few years, how many permits have been issued for a given watershed or impact zone.”

Instead, he suggested that CRD release more detailed information to the public with maps, permitting, specific work, rejections and approvals that’s searchable in various time periods.

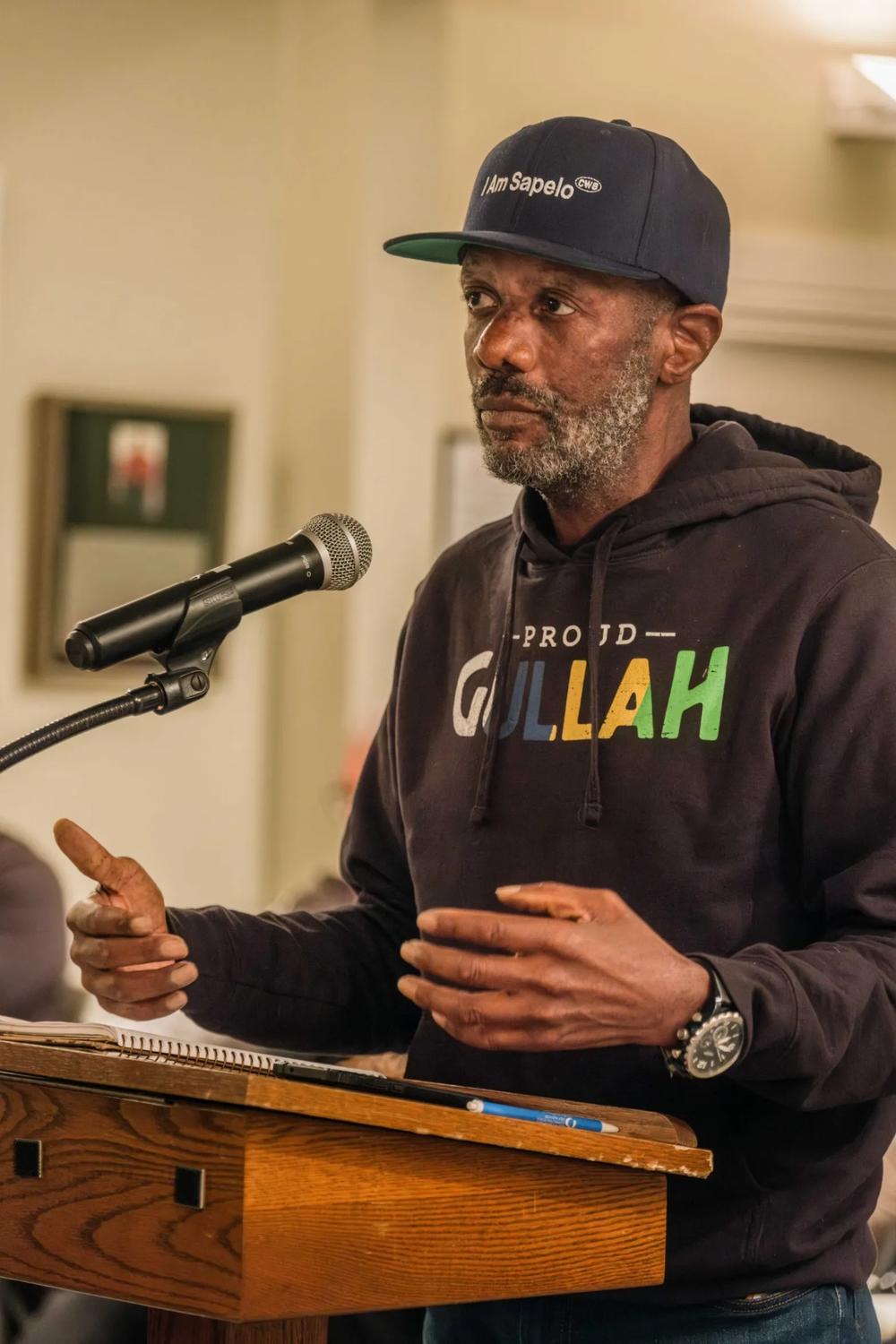

Josiah “Jazz” Watts, a Sapelo Island and St. Simons descendant, pleaded for the agency to protect coastal Georgia’s marshes from further environmental and cultural degradation.

Josiah Watts with One Hundred Miles.

Watts recalled when he could walk down the beach and not see development.

“When we’re talking about bulkheads, we’re also talking about development. That means there’s construction and building near these spaces on the coast and the marsh. These are spaces that have incredible value to us, to our lives, to our ecological system, to our growth — nature, resiliency, all those things come to mind for me,” he said.

He also noted that any stakeholder committee ought to include Sapelo descendants with direct ancestral ties to the islands.

Watts said his father, who worked for the Water and Sewer Department, warned him, “‘They’re developing. They’re developing this place way too fast, son. And the history and the culture are going to be at risk, and they’ll go with it.’….We’ve got to find ways to help people protect themselves from themselves as they continue to make these decisions that are, in the long run, very detrimental to these spaces. And that’s not even getting into the history and the culture that’s at risk.”

He urged CRD to “really engag[e] people that even have what I call indigenous knowledge in these spaces, that grew up in these spaces, and understood and still understand how the water flows, how the marshes breathe, and the importance of us protecting them. The coast is an amazing and beautiful place, and we should treasure it. And I think that some places should be sacred. Some places don’t need to be built on or built over.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.