Section Branding

Header Content

10 questions about the New Hampshire primary, including, 'Can anyone beat Trump?'

Primary Content

And it all comes down to this.

Former President Donald Trump won the Iowa caucuses in a blowout last week, confirming his dominance with conservatives. Candidates have dropped out and endorsed Trump, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who did so on Sunday.

Almost the entire Republican Party believes Trump will now be the nominee again and is rallying around him, excluding a minority of ex-candidates and his former U.N. ambassador, Nikki Haley.

So New Hampshire, which holds its primary Tuesday, with its moderate voter profile, offers what very likely will be the last, best chance for Haley to show she can beat Trump.

And she might have to win the primary to turn the narrative tide in her favor.

Here's everything you need to know about the New Hampshire primary:

Can anyone beat Trump?

Haley had been gaining ground on Trump in New Hampshire in recent weeks, but Trump continues to lead by double digits in polls — and the most recent ones suggest Haley's momentum may have cooled.

While New Hampshire certainly features a more moderate electorate than Iowa, there may be a ceiling to Haley's potential support. Voters will have their say Tuesday, and New Hampshire has offered surprises before that have turned the tide of presidential elections.

But a Marist poll of New Hampshire voters taken last week is revealing. Two-thirds of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents said Trump should have immunity from criminal prosecution for actions he took while he was president.

The survey underscored, though, Trump's potential general election problems. The poll found that two-thirds of the broader New Hampshire electorate, including independents and Democrats, felt he should not have immunity.

What time does voting take place?

All polling places must be open from at least 11 a.m. until 7 p.m. ET at a minimum, according to the secretary of state's office. Some polling locations have earlier hours or extend theirs, but all polls will be closed by 8 p.m. ET. (You can find hours for each polling location here.)

Because the 221 towns in the state have flexibility in their opening and closing times, a few of the most sparsely populated towns have used that to gain some attention by beginning voting at midnight.

The most famous example of this is Dixville Notch, which gained notoriety because it had predicted the eventual Republican nominee in every election from 1968 to 2012. That was broken in 2016 when it sided with former Ohio Gov. John Kasich over Trump. But the town, which is just 20 miles from the Canadian border, only has a population of 5. The vote in 2016 for Kasich was 3-2.

Who is allowed to vote?

This is maybe the biggest difference from the Iowa caucuses. Not only is this a state-run primary, rather than party-run caucuses, New Hampshire also allows independents, or undeclared voters, to cast a ballot in either the Republican or Democratic primary.

In addition to being generally a more moderate, suburban and less religious set of Republican voters than in Iowa, undeclared voters make up almost 40% of the state's registered voters.

Who will be on the ballot?

Even though most of the coverage has centered around the leading Republican candidates, there will be two dozen names that New Hampshire voters will see, including candidates who have already dropped out of the race. (Here's a sample ballot.)

For Democrats, it's a similar number — 21 people, including the likes of Paperboy Love Prince, Vermin Supreme, self-help author Marianne Williamson and Rep. Dean Phillips, D-Minn. Who it won't include is President Biden.

New Hampshire's primary won't be counted in this year's Democratic primary, because the Democratic Party demoted it in favor of South Carolina, which propelled Biden to the 2020 nomination.

There is, however, an active write-in campaign for Biden, which the party establishment has to hope wins. Otherwise, it would be a major black eye for the president.

Phillips, a wealthy former co-owner of Talenti Gelato, and a group supporting him have spent $5 million in ads in New Hampshire, including one employing Big Foot, or at least a man in a Big Foot outfit ... or is it?

What might turnout be like?

Secretary of State David Scanlan is predicting a record turnout of 322,000 for the GOP primary. The Republican turnout record is 282,979 set in 2016. New Hampshire traditionally has been one of the states with the highest participation rates in the country.

How much has been spent in New Hampshire?

Since the beginning of last year, $77.5 million has been spent on campaign ads targeting the state in the GOP primary, according to data compiled by the ad-tracking firm AdImpact and analyzed by NPR, as of Sunday afternoon. More than $10 million of that has come in just the past week — all for a state that allocates 22 delegates, or less than 1% of the total.

The top spender has been Haley and groups supporting her. Team Haley has poured in $30.9 million, almost doubling Trump and his allies, who have spent $15.7 million. A super PAC supporting DeSantis had spent about $8 million in New Hampshire, but Team DeSantis didn't spend anything after his distant second-place Iowa finish, before DeSantis dropped out and endorsed Trump on Sunday.

So why is New Hampshire important?

New Hampshire has voted first in primaries for more than 100 years. People in the state take a particular pride in the kind of retail campaigning and town halls it has traditionally taken to win the state. Of course, Trump has upended those traditions, as he's engaged in far fewer of those kinds of events, but New Hampshire has had a rebellious streak.

It has resurrected the campaigns of candidates thought to be finished in the primary, or solidified a candidate's position. In 2008, Republican John McCain, who had run out of money and was trailing in the polls, did more town halls in New Hampshire than anyone, won there and went on to the Republican nomination.

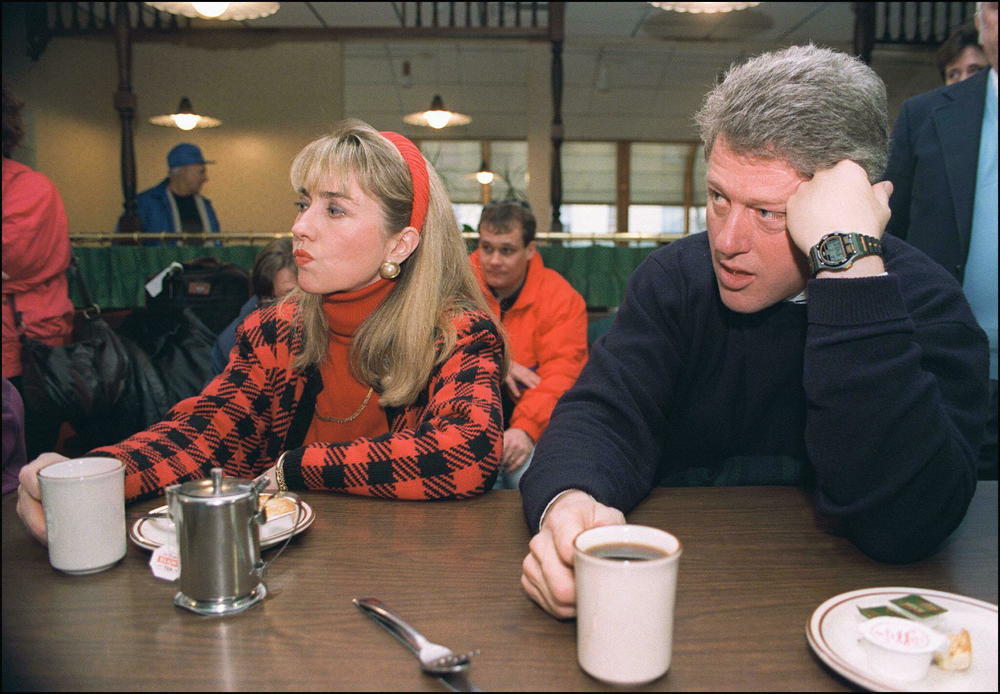

Bill Clinton's closer-than-expected second-place finish in 1992 led to him being labeled the "Comeback Kid," and he won the nomination. Sixteen years later, Clinton's wife, Hillary Clinton, was trailing Barack Obama in the polls after his surprise Iowa win. But Hillary Clinton pulled out the victory in New Hampshire. While she didn't win the nomination, her New Hampshire win gave new life to her campaign and led to the long, drawn-out primary fight that ensued.

Plus, on the Republican side, it has been a good predictor of who wins the GOP nomination. Since 1976, in a primary in which an incumbent Republican president wasn't on the ballot, six of the eight New Hampshire winners went on to win the nomination, including the last three. In that same stretch, only three Iowa winners became the nominee — and none of the last three.

It's why former New Hampshire Gov. John Sununu used to say about the two early nominating states that "Iowa picks corn; New Hampshire picks presidents."

Why is New Hampshire first?

New Hampshire became the first primary in 1920 after Minnesota dropped its primary, and Indiana moved to May. But until 1948, it only voted for delegates to the national convention, not directly for who people wanted to be president, as The Brookings Institution noted in this history of the primary in 2016:

"Until 1948, the New Hampshire primary, like most of the small number of other primaries in the country, listed only the names of locals who wanted to be delegates to the convention on the ballot. But in 1948, Richard F. Upton, speaker of the New Hampshire House of Representatives decided to make the primary 'more interesting and meaningful ... so there would be a greater turnout at the polls.' He did this by passing a law allowing citizens to vote directly for the presidential candidates."

It had an almost immediate impact. In 1952, with the Korean War continuing, Democratic President Harry Truman was unpopular and lost the New Hampshire primary. He decided against running for reelection. For Republicans that year, Dwight Eisenhower won and became the party nominee over Robert Taft, who had been seen as the party establishment's choice.

In 1968, during the Vietnam War, President Lyndon Johnson's narrow win over Eugene McCarthy was an early barometer of his unpopularity with his party. LBJ decided against running. McCarthy was popular with anti-war Democrats, but he was snubbed at the 1968 Democratic convention. The party selected Hubert Humphrey as its nominee, and that inflamed an already volatile situation in Chicago outside the convention hall between police and protesters.

That had an impact on not just Democratic politics, but the GOP, too. Democrats made changes to open up the primary process. More states gained influence, and New Hampshire's first-in-the-nation status was threatened.

So in 1975, following the 1968 convention, contentious primaries in 1972 and Watergate, New Hampshire passed a law, added to its state constitution, to cement its status as the first primary. It reads, in part:

"The presidential primary election shall be held on the second Tuesday in March or on a date selected by the secretary of state which is 7 days or more immediately preceding the date on which any other state shall hold a similar election ..."

In the 1980s, Iowa and New Hampshire struck a deal allowing Iowa to hold the first caucus and New Hampshire the first primary.

Has there been any drama?

Lots. New Hampshire has been known for tears and dirty tricks.

A couple of examples stand out. It included a hoax letter that actually was planted by Republican Richard Nixon's campaign. It falsely accused a leading Democratic candidate, Edmund Muskie, of using an ethnic slur that led Muskie to (maybe) cry in a public outburst, while also defending his wife, whom a local newspaper accused of liking "to tell dirty jokes and smoke cigarettes."

Ooooh.

Tame stuff by today's standards, but it was hot in 1972.

"It changed people's minds about me, of what kind of guy I was," Muskie said of the moment. "They were looking for a strong, steady man, and here I was, weak."

In 2008, it was the reverse. Hillary Clinton got choked up during an event answering a question from a voter. That gained lots of attention and may have actually turned around her fortunes in the Granite State.

What's next?

After New Hampshire, it's Nevada, which confusingly is holding a state-run primary on Feb. 6 and a party caucus on Feb. 8.

The party will award its delegates based on the caucus. Trump will be on that ballot, but Haley won't. Haley will be on the primary ballot, but Trump won't.

But Nevada has not been a focus of the candidates. Only about $1 million has been spent there so far.

After that, it's South Carolina on Feb. 24. About $9 million in ads have been run there, far less than Iowa and New Hampshire, and Trump leads by a significant margin in the polls.

South Carolina has a very conservative electorate, and a Trump win there would put Haley in the very awkward position of losing in the state that elected her governor. That will be difficult for her and her campaign to explain away.

If that happens it could mean Trump wraps up the nomination by late March. And then it will be, for anyone not named Trump, as the song goes, all over but the crying.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.