Section Branding

Header Content

'We don't want to be first place.' Wyoming tries to address high gun suicide rates

Primary Content

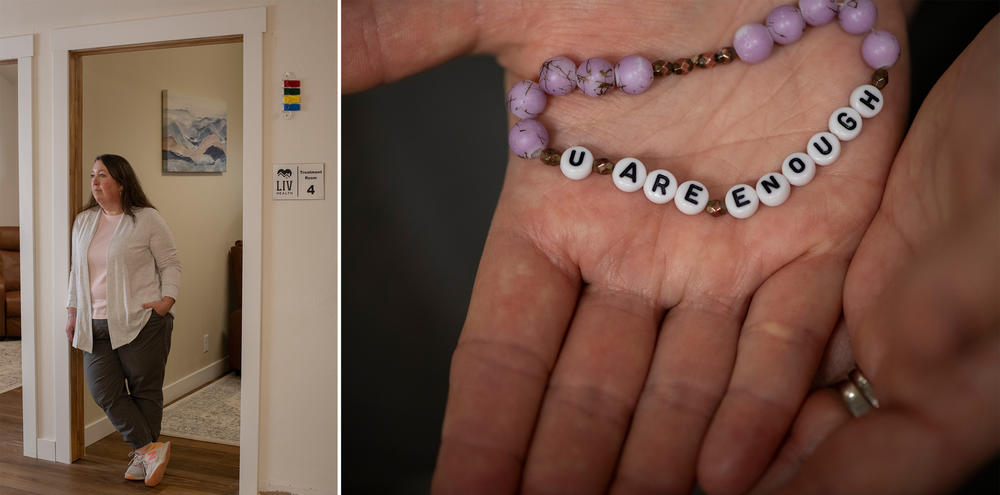

CHEYENNE, Wyo. — Shortly after Christina Williams' fiancé died last spring, her three daughters came to her crying. They said they missed their dad. It got to be too much for her.

"I couldn't handle my grief or my girls' grief at the same time," Williams says.

She made a plan, as grief counselors call it, to take her life that day. But by chance, a couple of hours later, while stopped at a traffic light on Dell Range Boulevard in Cheyenne, she saw a sign for LIV Health, a newly opened mental health urgent care clinic.

She decided to drive in right then. Without an appointment, she was seen immediately by a crisis clinician and a psychiatric nurse practitioner.

One of the first questions that crisis clinician Sarai Guerrero-Vasquez asked Williams when she first came in is now an increasingly normal standard across Wyoming: Where are the guns stored at home?

"I always assure them, 'I'm just a social worker — I'm not going to go into your house and take anything,'" Guerrero-Vasquez says. "I just want to make sure that you stay safe, and if that means having a family member secure them for a little bit until you go through this bump, life will resume."

Williams had already given hers to her best friend. Soon after her visit to LIV Health, she agreed to check herself into the hospital and has since been doing better — getting regular counseling and help managing medications. But Guerrero-Vasquez says some patients resist getting more treatment because they're afraid their guns will be confiscated.

This is the reality of suicide prevention work in a state with one of the highest gun ownership rates in the United States. For most of the last decade, Wyoming has also had one of the highest suicide rates and, specifically, high gun suicide rates. Firearms are used in roughly 75% of suicides in the Cowboy State, compared with just over 50% nationally.

In conservative Wyoming, it was long seen as taboo to draw a link between guns and suicide.

But survivors and those who work in prevention say there are signs that this is finally changing, with gun shops increasingly talking about safe storage of firearms, and mental health professionals talking more with patients about the risks of easy access to guns during a mental health crisis.

"Cowboying up" to get through a mental health crisis

There are a lot of theories behind why Wyoming, alongside several of its neighbors in the Mountain West, has had perennially high suicide rates. It's the least populated state in the nation, and there are huge gaps in care. People have to drive long distances on roads that often close for blizzards or wind. There has also long been a stigma around getting help: that "cowboy up" mentality of getting through the tough times.

But those who work on the front lines of suicide prevention say there's another, bigger elephant in the room. And that's all the guns and easy access to them.

"One of the challenging aspects of working in the Rocky Mountain region is just the availability and accessibility of firearms," says Brittany Wardle, a prevention officer at Cheyenne Regional Medical Center. "Some days it feels very overwhelming because you think, 'If we didn't have firearms to worry about, what would suicide look like here?'"

But gun control in Wyoming is widely seen as being off the table. It's also unlikely the state will expand Medicaid anytime soon, which experts say could increase mental health services.

Still, those who work in suicide prevention see some incremental signs of progress. Wyoming now has a locally staffed 988 suicide hotline. Gov. Mark Gordon has been holding high-profile suicide prevention forums in communities, garnering press attention. And efforts to expand mental health care to underserved places — such as the new urgent care clinic in Cheyenne — could serve as a model for other communities.

LIV Health has seen a 171% increase in patients since last year. Similar clinics have been popping up around the country since 2020. In rural America, it can take months to get a regular appointment with a mental health specialist, and providers say people in crisis need help immediately.

Suicide by firearm is 97% lethal

In the urgent care clinic's lobby, next to the requisite doctor's office magazines, LIV Health CEO Emily Loos restocks a basket full of free gun safety locks every couple of weeks. Clinic staff members stress the importance of safely storing guns or giving them up temporarily in a time of crisis.

"If we're worried about impulsivity, [we say] you can put the key somewhere up high where you really have to work to get to it," Loos says. "If they're hesitant to give up their firearm, we'll talk about making it harder to access within the home."

Even though Wyoming has remained at or near the top in the nation for per capita suicides, B.J. Ayers is at least encouraged that folks are finally talking openly about keeping guns away from people in a moment of crisis.

It's something she knows all too well. The Cheyenne mother lost two sons to suicide more than a decade ago. Both shot themselves.

"I mean, at what point do we say enough is enough?" Ayers says. "We need to talk about it. We need to get the resources out to the people that are in crisis."

Unlike, say, intentional drug overdoses, suicide by firearm is almost always lethal. After her sons' deaths, Ayers, who is 62 and works as an insurance agent, channeled her grief into action, starting a suicide prevention foundation.

"It's very disheartening when we stay up there," she says, of her state's ranking on guns and suicide. "We don't want to be first place in this."

A push for safe storage as an alternative to red flag laws

In blue America, the reflexive response to gun violence is often a move to restrict access to firearms. With gun control a nonstarter here, prevention workers like Lauren SinClair of the Department of Veterans Affairs talk instead about creating time and space between a person in crisis and a gun.

One recent week, she had logged hundreds of miles in her Toyota hybrid minivan crisscrossing southern Wyoming visiting local gun shops and advocating for safe storage — where a customer can bring their guns in and store them temporarily in a safe, no questions asked.

At an unannounced drop-in at Frontier Arms & Supply in Cheyenne, she explained to counter staff: "Maybe their teenager is in crisis or they themselves were just saying, 'Hey, I'm not in the right space to have my firearm at home with me right now. Can you hold that?'"

She was pleased to learn that the shop was already offering this service and getting willing participants. SinClair lost her mother to suicide by firearm when she was a little girl. She says that for too long, suicide prevention and guns were completely siloed from one another in Wyoming.

"They can coexist together: mental health professionals talking about firearms, firearms professionals talking about mental health," SinClair says. "Those can exist together, and I think for too long there was hesitancy."

It's not yet clear how many gun shops are offering safe storage in Wyoming. But it's now more common for salespeople to hand out safety locks with purchases and to have taken suicide prevention trainings known as QPR classes — question, persuade, refer.

A local prevention tool that doesn't involve politics

On the outskirts of the wind-swept town of Laramie is Gold Spur Outfitters, a specialty gun retailer popular with local college students. Behind the store and warehouse floor is a huge metal vault. On closer inspection, it's a secure room, not unlike a large safe.

Co-owner Lloyd Baker incorporated safe storage into his business model when he opened three years ago, after seeing so many fellow veterans battling mental health challenges.

"Something like this is not going to solve all the problems. But it's a start," Baker says. "We're not here to judge. We're not here to point fingers. We're here to reduce the stigma, first off, around firearm storage and mental health."

Baker is working with the new Firearms Research Center across town at the University of Wyoming to turn this into a model statewide. He's frustrated with what he sees as the gridlock in American politics: Many liberals default to gun control, and most conservatives just say no to anything.

"We can provide tools to the people who do suicide prevention," Baker says. "There are other options than going through state or federal government to try to fix a local problem. Maybe we can do something locally."

He's referring to the alternative to red flag laws, which have been effective in blue states, including next door in Colorado, where a judge can temporarily remove guns during a mental health crisis. In a rural culture where there's often deep mistrust in government, Baker says, gun owners — including some of his most loyal customers — tend to have better relationships with their local dealers.

Still, despite all the work underway, Wyoming was expected to finish out 2023 at or near the top in the nation for suicides.

It's frustrating to survivors like Kari Cochran who are turning their grief into action.

In Rock Springs, she lost her 18-year-old son last year to suicide. He had battled mental health challenges his entire life and shot himself after going missing in February.

"He left the house. He talked about buying a gun. At that point, I didn't think he had access," Cochran says.

Cochran, a local hairdresser, was elected to her local school board recently in part on a platform of increasing mental health access for students. She says she'll work as hard as she can to ensure that no other family has to endure the pain hers is going through.

"It's a system problem that just is going to continue to repeat itself until we show kids and talk to kids openly. I mean, guns aren't going away," she says.

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or be in crisis, call or text 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.