Section Branding

Header Content

A famous climate scientist is in court with big stakes for attacks on science

Primary Content

In a D.C. courtroom, a trial is wrapping up this week with big stakes for climate science. One of the world's most prominent climate scientists is suing a right-wing author and a policy analyst for defamation.

The case comes at a time when attacks on scientists are proliferating, says Peter Hotez, professor of Pediatrics and Molecular Virology at Baylor College of Medicine. Even as misinformation about scientists and their work keeps growing, Hotez says scientists haven't yet found a good way to respond.

"The reason we're sort of fumbling at this is it's unprecedented. And there is no roadmap," he says.

A famous graph becomes a target

The climate scientist at the center of this trial is Michael Mann. The professor of earth and environmental science at the University of Pennsylvania gained prominence for helping make one of the most accessible, consequential graphs in the history of climate science.

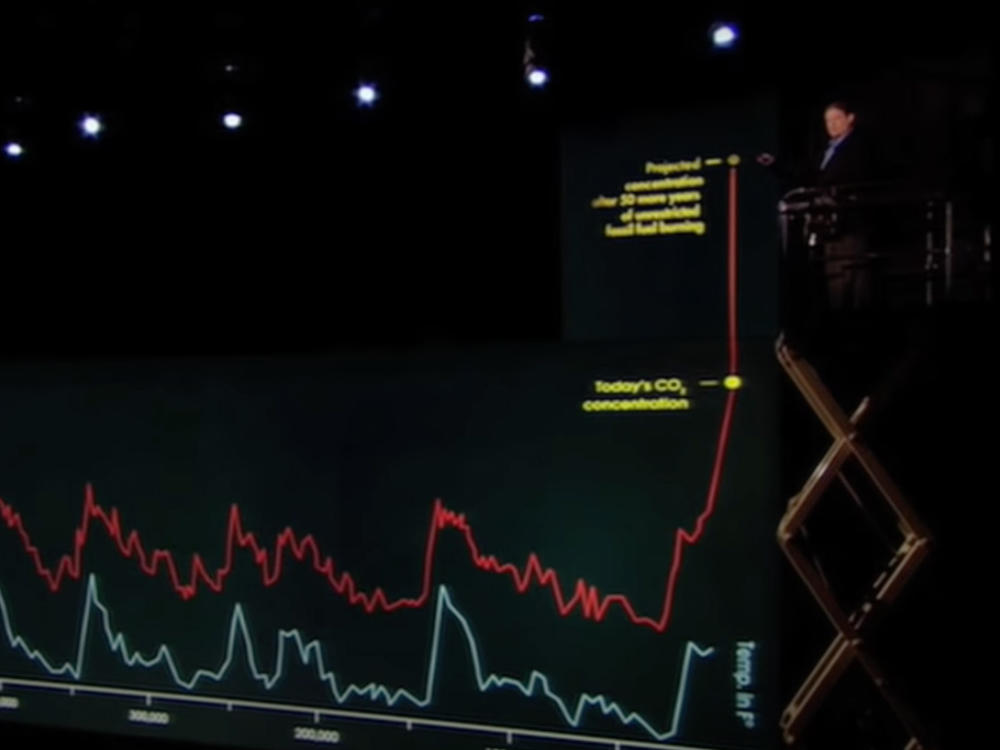

First published in the late 1990s, the graph shows thousands of years of relatively stable global temperatures. Then, when humans start burning lots of coal and oil, it shows a spike upward. Mann's graph looks like a hockey stick lying on its side, with the blade sticking straight up.

The so-called "hockey stick graph" was successful in helping the public understand the urgency of global warming, and that made it a target, says Kert Davies, director of special investigations at the Center for Climate Integrity, a climate accountability nonprofit. "Because it became such a powerful image, it was under attack from the beginning," he says.

The attacks came from groups that reject climate science, some funded by the fossil fuel industry. In the midst of these types of attacks — including the hacking of Mann's and other scientists' emails by unknown hackers — Penn State, where Mann was then working, opened an investigation into his research. Penn State, as well as the National Science Foundation, found no evidence of scientific misconduct. But a policy analyst and an author wrote that they were not convinced.

The trial, more than a decade in the making

The trial in D.C. Superior Court involves posts from right-wing author Mark Steyn and policy analyst Rand Simberg. In an online post, Simberg compared Mann to former Penn State football coach Jerry Sandusky, a convicted child sex abuser. Simberg wrote that Mann was the "Sandusky of climate science," writing that Mann "molested and tortured data." Steyn called Mann's research fraudulent.

Mann sued the two men for defamation. Mann also sued the publishers of the posts, National Review and the Competitive Enterprise Institute, but in 2021, the court ruled they couldn't be held liable.

In court, Mann has argued that he lost funding and research opportunities. Steyn said in court that if Penn State's president, Graham Spanier, covered up child sexual assault, why wouldn't he cover up for Mann's science. The science in question used ice cores and tree rings to estimate Earth's past temperatures.

"If Graham Spanier is prepared to cover up child rape, week in, week out, year in, year out, why would he be the least bit squeamish about covering up a bit of hanky panky with the tree rings and the ice cores?" Steyn asked the court.

Mann and Steyn declined to speak to NPR during the ongoing trial. One of Simberg's lawyers, Victoria Weatherford, said "inflammatory does not equal defamatory" and that her client is allowed to express his opinion, even if it were wrong.

"No matter how offensive or distasteful or heated it is," Weatherford tells NPR, "that speech is absolutely protected under the First Amendment when it's said against a public figure, if the person saying it believed that what they said was true."

Many scientists under attack

Mann isn't the only climate scientist facing attacks, says Lauren Kurtz, executive director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund.

"We help more scientists every year than the year before," Kurtz says. "We actually broke a record in 2023. We helped over 50 researchers."

Dozens of climate scientists from the federal government have contacted her group in recent years, many alleging that they were censored under the Trump administration. During his presidency Donald Trump denied the science of climate change and pulled the U.S. out of the U.N. Paris Climate Agreement addressing global warming.

But while climate researchers were early targets of people rejecting peer-reviewed science, now those attacks have spread to biomedical scientists, supercharged by the COVID-19 pandemic. Kurtz says while they primarily provide legal defense for climate researchers, they've recently heard from COVID-19 researchers, too.

Hotez worries about the ramifications for the future of science and medicine. He says: "Young people, looking at future careers, looking at how scientists are attacked are going to say, 'Well, why do I want to go into this profession?'"

Solutions for attacks on scientists

Hotez says he's glad Mann is fighting back in court. But he doesn't think a bunch of lawsuits is a sustainable solution. And he says he wants to keep working in the lab.

"We have a new human hookworm vaccine that'll come online soon," he says. "That's how I want to spend my time. I don't want to spend my day making cold calls to plaintiff lawyers."

Imran Ahmed, chief executive at the Center for Countering Digital Hate, says any response has to include social media companies, as that's where attacks on scientists happen every day. Research finds that social media platforms can encourage the spread of scientific and medical misinformation.

Hotez says he and Mann are working on an upcoming project, collaborating on what they see as overlap in attacks on climate science and biomedicine and how to counter it.