Section Branding

Header Content

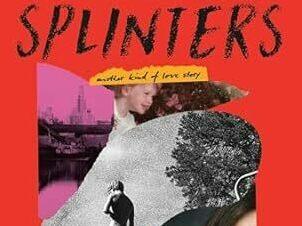

'Splinters' is a tribute to the love of a mother for a daughter

Primary Content

When Leslie Jamison's daughter was 13 months old, she and her husband, the baby's father, C, separated.

Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story, the famed essayist's newest book, follows this rupture — some of what preceded it but mostly what came after. The book has received plenty of advance buzz, much of which positions it as being about her relationship with C and their divorce, which I found puzzling; C is certainly a part of the book, but a small one, flitting in and out of view, never coming into full focus. His privacy is kept intact — Jamison mentions a child from his first marriage and acknowledges that she and C agreed she wouldn't write about them — to the point where he presents as somewhat of a cypher. Which is to say that readers looking for a juicy narrative mired in the throes of marital drama will be disappointed. Those who take the book's subtitle seriously, however, will find much to admire and enjoy in its pages, which are, more than anything else, a tribute to the rapturous love Jamison has for her daughter, as well as her attempts to love, or at least accept, the parts of herself that thrive in intensity and turmoil.

Jamison briefly narrates the whirlwind relationship she and C had, how he casually proposed to her while they were lying in bed in a garret in Paris. She's aware, at least in hindsight, that she agreed to the marriage less because she wanted to commit to him, specifically, or to the life that the two of them as particular individuals could build. Instead, she admits: "I said yes, because I was in love with him, and because I wanted my whole self to want something, no questions asked." When they married shortly thereafter in Las Vegas, she hoped she "could become a person who didn't change [her] mind. That sounds ridiculous when you say it plainly, but who hasn't yearned for it? Who hasn't wanted a binding contract with the self?" This is the book's second major thread — in addition to her daughter — the desire for consistency, and the stories the author tells herself or tries to fit herself into, in order to find it.

There is a circularity to Splinters; over and over again, in different variations of her signature, beautifully frank language, Jamison writes about her fantasy of stability and her uncertainty as to whether it's a dream she actually wants fulfilled. Is it easier for her to simply want some kind of solidity? Is the yearning itself providing a steadiness all its own? The question becomes somewhat moot when her daughter is born; an infant and later a toddler's need for their parent is nothing if not consistent, ongoing, and inescapable.

Other aspects of Jamison's life don't remain particularly steady. Over the course of the book, she begins to date again and becomes completely infatuated with a man with whom she knows she will never settle down since he's not the settling type, a fact he makes clear early on. Later, once the intensity of this love affair is over, she begins dating someone who is in some ways the ideal of security, a man who works at a hedge fund and paints abstract art on the side. He also brings out Jamison's painful self-minimizing tendencies; she wants to impress him, to be the kind of person he wants her to be, to gain and keep his approval. She recognizes this — but self-awareness alone is rarely enough to get most of us to change behaviors we've become uncomfortably comfortable with.

Throughout the book, Jamison brings in the work of other artists and writers that she admires, merging her creative and parental roles by bringing her infant daughter to museums with her, or by discovering how other parent-artists brought their own children into their artwork — or didn't. There's no waxing poetic over the way having a child brings so much more inspiration into one's life, but there's also no doom-and-gloom prophecies about a child bringing to an end one's creative endeavors, a balance which I personally found especially pleasing as a writer and expecting parent myself. Elsewhere Jamison knows she has trouble dwelling in the gray areas, preferring the certainties of extremes, but in caring for her daughter, she finds — at least on the page — a way to live with it all, the sleeplessness and the joy, the rapture and the frustration, the immense love and the wish to have a single moment alone.

Splinters doesn't provide a unifying revelation, and even though it's relatively linear, Jamison doesn't end up in a place that's so different from where she started out. This can be easy to overlook, as she's a master at closing nearly every paragraph with what lands as an epiphany: "There was a clarity to him — to his passion, and even to his anger — that felt clean and stark, like a rugged landscape with all the fog burned off" or "The moral of the story was: Forget about the story. Just take care of your daughter" or "I wasn't sure anyone would root for me, if she wasn't my friend or my mom. I wasn't sure what narrative arc I was tracking, or what ending I deserved."

But in truth, Jamison knows from the very start of the book what she struggles with, and what the grand challenge of her life has been, and might well continue to be: "To stop fetishizing the delusion of pure feeling, or a love unpolluted by damage. To commit to the compromised version instead." It's easier said than done, of course; but Splinters is a beautiful tribute to the continued failure as well as the worthy ongoing attempt.

Ilana Masad is a fiction writer, book critic, and author of the novel All My Mother's Lovers.