Caption

This Ledger-Enquirer file photo is from the mortgage burning celebration and historic marker dedication at Saint James A.M.E. Church in Columbus, Ga.

Credit: Ed Ellis / Ledger-Enquirer

This Ledger-Enquirer file photo is from the mortgage burning celebration and historic marker dedication at Saint James A.M.E. Church in Columbus, Ga.

A few months ago, a Ledger-Enquirer reader asked Curious Columbus a question about Muscogee County’s past.

“What is the history of racism in Columbus, Ga.?” Daniel Todt wanted to know.

This question seems overwhelming considering the Southern city’s long history that includes the Ku Klux Klan, a landmark Supreme Court case, desegregation and a visit from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. following the murder of a local civil rights leader.

Standing on 6th Avenue, with its center spire and twin turrets reaching into the sky, St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church has seen much of this history. As the second oldest church of the denomination in Georgia, the history is woven into St. James’ architecture and the stories of past and current members.

Enslaved individuals built the heavy, ornately carved front doors that were given to the church’s founders less than 10 years before the Emancipation Proclamation. The building’s ceiling is designed like the bottom of a slave ship, a reminder of the church’s forefathers.

St. James’ founders previously attended St. Luke before being allowed to worship by themselves in 1858, said Carolyn Hensley, a church historian.

Historically Black churches became a cultural cornerstone because of the need for both social and spiritual awareness, St. James A.M.E. pastor B.A. Hart told the Ledger-Enquirer.

From the beginning, St. James A.M.E. proudly encouraged education among its congregation even when Jim Crow laws made getting an education difficult.

In the past, people didn’t want African Americans to read, Hart said, especially the Bible because they would have become more enlightened with God’s word. St. James is proud of its history, he said, and the church encourages its congregation to grow its skills and abilities unhindered.

“Let me use the theology of James Brown,” Hart said. “He said ‘I don’t want nobody to give me nothing. Open up the door, I’ll get it myself.’”

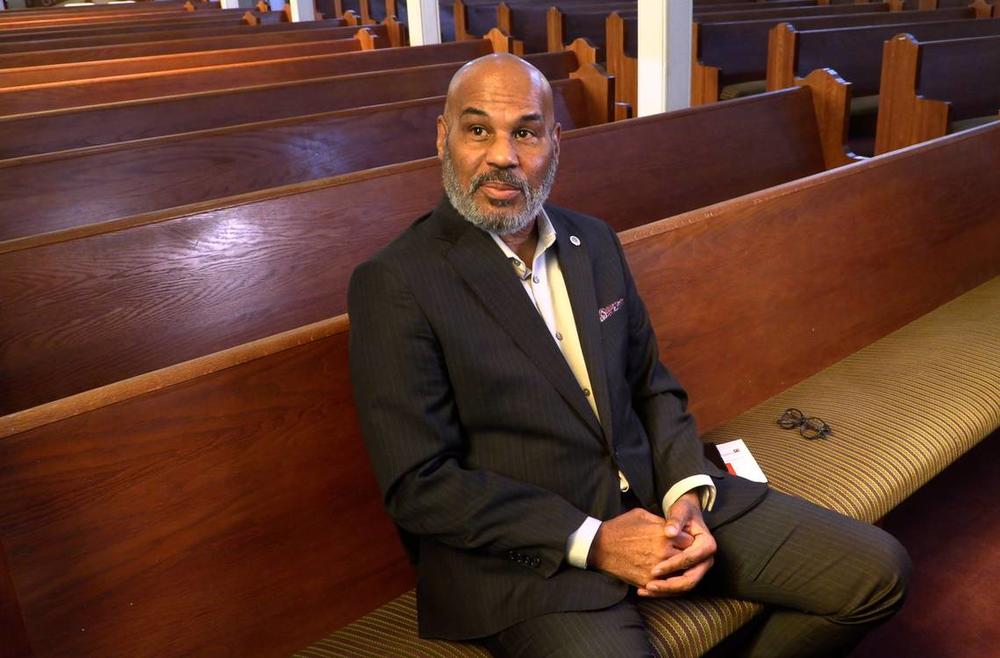

The Rev. B. A. Hart is the senior pastor at Saint James A.M.E. Church in Columbus, Ga.

St. James’ history shows the first step to growing skills and abilities in the face of obstacles is through education.

In her role as a church historian, Hensley preserves history with images and documents from the past.

The church was not known as St. James initially in Columbus’ history, Hensley said. They were originally the A.M.E. Church on 6th Avenue.

“When we became a school, we were the 6th Avenue School at the A.M.E. Church,” she said. “We didn’t get our name until 1863.”

One of the images Hensley possesses is of the St. James A.M.E. Church School faculty from 1905.

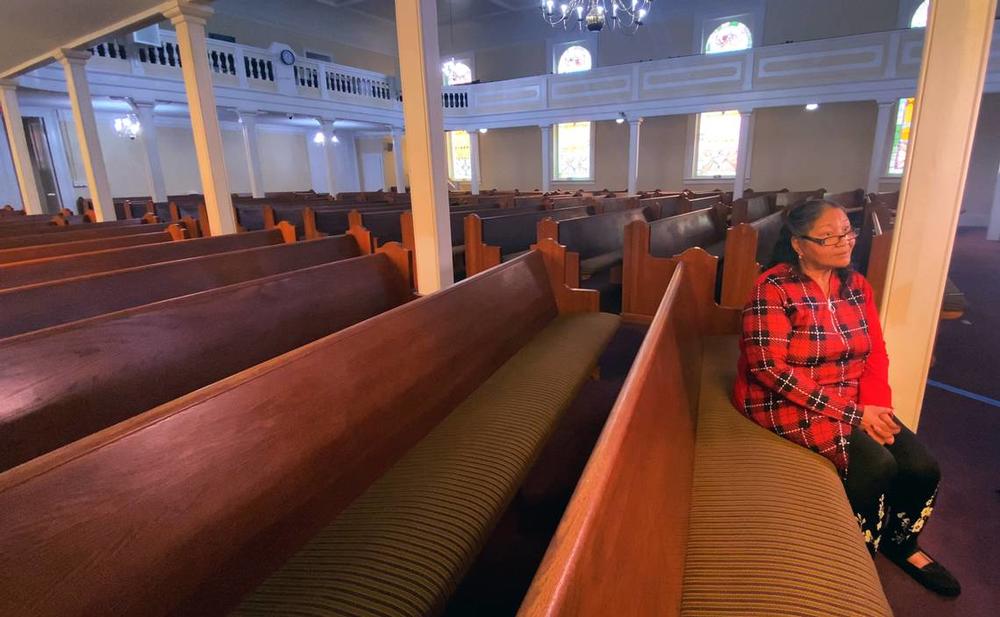

Carolyn Hensley, the church historian at Saint James A.M.E. Church in Columbus, Ga., holds a photograph of the 1905 faculty of the church’s school.

Everyone in the photo dressed to impress, Hensley said.

“And they taught their students to carry themselves in such a way to be proud of themselves by going to school here,” she said.

Posing in front of St. James’ iconic doors along with the impeccably dressed teachers stood Professor William H. Spencer, the head of St. James’ school and the namesake of Spencer High School.

Spencer served as the supervisor of the Negro Educational Department and principal of the former Fifth Avenue School during his 50-year career in education.

He was dedicated to opening a high school for African American students in Columbus, who had to travel as far as Atlanta to receive an education beyond the eighth grade during segregation.

He was successful in his endeavor as the original William Henry Spencer High School opened on 10th Avenue in 1930.

“Sadly, he didn’t live to see it,” Hensley lamented.

Spencer died five years earlier on May 30, 1925.

Carolyn Hensley is the church historian at Saint James African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church of Columbus, Ga.

Throughout St. James’ history, the church prided itself on encouraging education and uplifting members to work in professional careers.

Along with Spencer, other St. James A.M.E. educators who’ve had schools named after them include Shadrach Marshall, J.D. Davis and Lyda Hannan.

“We did have people who aspired to be doctors and mostly educators,” Hensley said. “You’ll see a lot of educators came out of our church.”

James Bussey, 97, didn’t know to be angry when he passed the white school two blocks from his home to go to the Black school further away.

His family sheltered him from the impact of segregation when he was a child.

But they couldn’t shelter Bussey from everything.

He felt fear when the Ku Klux Klan dressed in white robes and drove through his primarily Black East Highlands neighborhood loudly blowing horns twice a month.

“It was fear that they demonstrated,” he told the Ledger-Enquirer. “Stay in your place, or we will burn your house down. Or we’re going to burn a cross in your yard to warn you.”

Bussey followed his grandmother’s rules when he left home.

“You gotta have manners,” he said. “How do you behave around white people? Be obedient and submissive because it might save your life.”

Fear prevented Bussey from being active in the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King Jr., in Montgomery, Ala., in 1956.

Fear prevented St. James A.M.E. from hosting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. when he gave a speech to more than 1,000 people at the Prince Hall Masonic Temple in 1958.

King’s visit followed the murder of Dr. Thomas Brewer, a Columbus activist who helped organize and finance the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision, King v. Chapman, that ended the white primary system in Georgia.

Primus King, a Columbus barber and minister, challenged the system by attempting to vote in a primary election in Muscogee County on July 4, 1944. Brewer, a tactician for the local NAACP, helped orchestrate the strategy.

Lula Lunsford, a St. James A.M.E. member and grandmother of Muscogee County Tax Commissioner Lula Huff, was also a prominent figure in fundraising to support the case.

After Brewer was killed, local Black churches feared Klan bombings if they hosted King, so the Prince Hall masons invited the civil rights leader to prevent retaliation against the churches.

Bussey didn’t attend the speech.

But when Bussey’s daughter, Dr. Janet Bussey, applied to attend Columbus High School during desegregation after being inspired by others at St. James, he was no longer afraid.

In the aftermath of the Brown v. Board of Education, the Muscogee County School District, like many other Southern school districts, was slow to desegregate its schools.

After facing pressure, the school board approved a freedom of choice plan to desegregate starting in 1964.

During this time, college students from Columbus who attended St. James A.M.E. were coming back to the church sharing their stories about participating in the civil rights movement. Janet, who was in high school, took it all in.

“They were participating in these marches, and arrests, and fire hoses and dogs,” she said. “And would come back and talk about it to us…It was so scary.”

Saint James A.M.E. Church, located at 1002 6th Ave. in Columbus, Ga., is of historic significance and included on Columbus’ Black Heritage Trail.

A.J. McClung, a Columbus educator and politician and member of St. James A.M.E., spoke to the congregation encouraging high school students to participate in the school district’s desegregation plan.

The city did not want to desegregate the schools, McClung told the congregation, and argued its Black and White residents were happy staying in separate schools.

“They’re counting on nobody applying,” Janet recounts McClung’s plea to the congregation. “The deadline is coming up, and then they’re going to say, ‘See, we told you.’”

Encouraged by the activism of the older students, Janet felt applying to attend Columbus High School wasn’t too much to ask for. She wouldn’t go to jail or get beaten. She would just attend school.

When Janet decided to apply, Bussey was proud of his daughter. He supported Janet by driving her to school each day alongside her classmates.

“I didn’t feel any fear,” Bussey said. “I was ready to protect her.”

James Bussey, 97, a member of Saint James A.M.E. Church in Columbus since the early 1950s, and his daughter, Dr. Janet Bussey, talk about the church’s history.

Janet was the only student in the congregation to apply, and began attending Columbus High School in the 10th grade. There were 11 Black students in her grade, six juniors and one senior.

Education is the legacy of St. James A.M.E., Hensley said.

Up until the pandemic began, the church hosted GED classes and provided a computer room. St. James will continue to honor its history without “living in yesterday,” Hart said.

“They left that legacy with us to continue to teach and to continue to educate,” Hensley said. “Not just in the classroom, but in the community.”

Do you have a question about something you’ve seen or wondered about in Columbus. Fill out the following form to have your questions answered in the next Curious Columbus.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Ledger-Enquirer.