Section Branding

Header Content

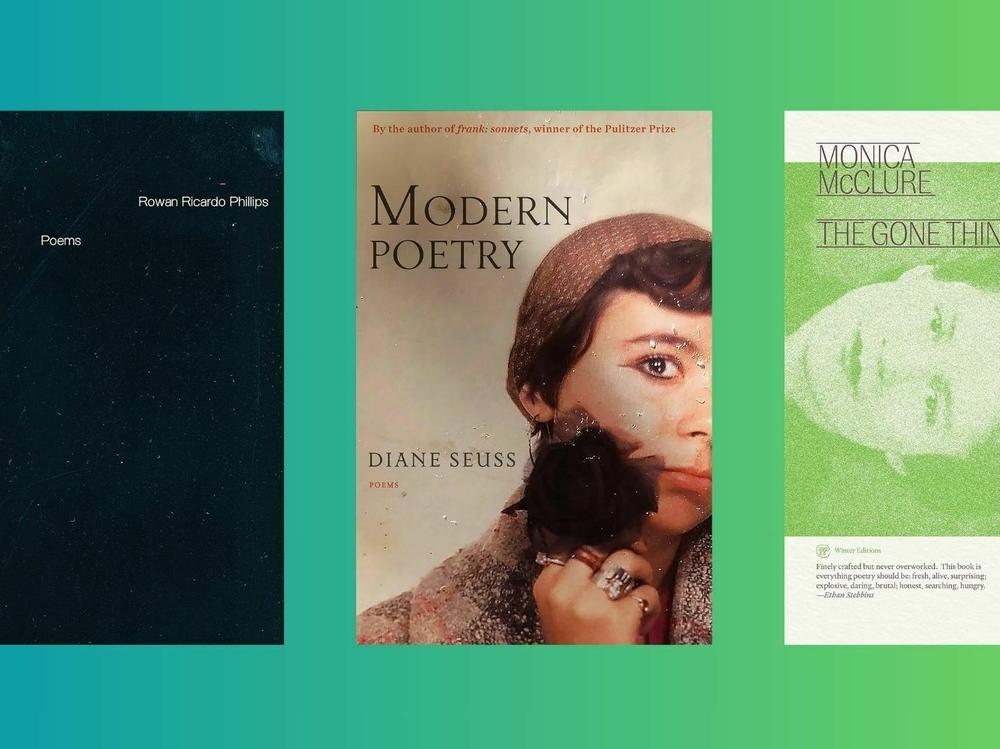

3 collections take the poetic measure of America in the aftermath of the pandemic

Primary Content

Every time I write a book review lately, I seem to start by saying something like this: Here are three poets responding in different ways to this deeply terrifying time, when the personal and the political are utterly inextricable and life is everywhere at stake. This review is no different.

In their new collections, poets Monica McClure, Rowan Ricardo Phillips, and Diane Seuss are all taking the poetic measure of America in the aftermath of the pandemic, as the whole country suffers a tremendous crisis of faith in itself. Each of them offers poetry as, if not a solution, then a kind of truth-telling companion, a mirror with a real person on both sides of it.

The Gone Thing

Monica McClure is one of my favorite contemporary poets. The Gone Thing, her follow-up to Tender Data, her mind-bending 2015 debut, is powered by the tension between seemingly contrary forces: money and poverty; the too-cool-for-you world of couture fashion and utter vulnerability; art and office life; motherhood and daughterhood. It's a book about borders — the U.S. southern border, the borders between high and low culture, between McClure's Mexican heritage and her cosmopolitan New York life, and between humor and dire seriousness. It's all rolled into one slippery sensibility, equal parts social critique and personal excavation.

With arresting simplicity, McClure paraphrases the basic message the United States has for immigrants: "It's a crime to be born poor/ It's treason to stay that way." This double bind is presented in countless ways throughout the poems. "Nothing shocks me," writes McClure in "Serving Many Masters," a poem that tallies the costs of success in a society bent on keeping the poor poor and powerless: "Don't get up if you're not/ Ready to crawl."

The poems also hint that a baby is on the horizon, and McClure tries to envision how to safely bring a child into such a fallen world, where "at best, I can do an interpretation of justice/ And hope it doesn't go up in smoke." How can one explain post-Trump America to a child who "will live/ Where people who are better than me/ Had their babies wrenched from their arms,/ Scattered to the winds"?

McClure's means of facing this entrapment is to reclaim the language, to ice it with biting humor, and to use it against itself, to defy categories, to be more than one thing at once: "You're an earner/ as well as a mother You're a midwife to conversations.," she writes in the long title poem, which closes the book. We are in desperate need of those conversations — perhaps they'll start here.

Modern Poetry

"The danger/ of memory is going/ to it for respite," writes Diana Seuss in "Weeds," the best poem in her first collection following the Pulitzer-winning Frank. On page after page, she asks: How can we bear to live in the present, given what a mess it is, but also avoid living in memory, which, she says, is a trap? Seuss, too, comes to poetry as a means of survival, though, for her, even retreating into poetry risks painting things with a false glimmer: "What luxury to think of milkweed cars/ and cookie jars and turning lights on in the dark."

These extemporaneous poems reckon with the past, have their say, almost lightheartedly romping through meditations on whatever she feels like thinking about, often poetry and The Great Poets of the past (Gerard Manley Hopkins, Wallace Stevens, Theodore Roethke), but also the pandemic, love, and all the suffering that comes with it.

In what amounts to a book-length origin story, Seuss explains how she became a poet, finding, if not beauty, then at least a sense of mission in repurposing the ugliness she encounters: "I could find some things repulsive and still/ require them for my project. My project/ was my life." She takes us on a tour of "the desolate town where I was raised," and where she became familiar with "that icky-sweet smell of a dead mouse in the wall." Like an off-beat Virgil, she tosses off gems of odd aphoristic wisdom ("Every town has a two-headed something") and makes poetry more accessible by mixing in a bit of pop culture: "Keats made such a compact corpse,/ Only five feet tall, shorter than Prince." Finally, she wonders whether poetry is mostly a home for misfits: "What did modern poetry really mean? Maybe/ just fucked up."

I am a late convert to the cult of Seuss, but came around forcefully to Frank and the many ways it finds to explode the sonnet form while also taking advantage of its tradition and its argumentative powers. Modern Poetry lacks the rigor of that book, as if to say it's simply foolish to try to tame all this pain. I do think the box of the sonnet did something useful for Seuss's poetry, organizing her improvisations. I miss that rigor, but maybe disorder is part of the message: "A cobbled mind," she notes, "is not fatal."

Silver

"No one is ever alone with their thoughts," writes Rowan Ricardo Phillips in his fourth collection. To meet an increasingly isolating and terrifying era, Phillips retrenches in poetry, which, he claims, can be found everywhere. "The imagination hides in plain sight." Poetry stands by us, ready, Phillips seems to say, to console us with the truth, whether or not we want to hear it.

Only poetry, Phillips suggests, can express the horrendous illogic of our moment, which may be "like real flowers in a field/ Of memes or a meme in a filed of real/ Flowers." And when it fails as a stay against confusion, poetry holds our grief, stores the unresolved: "George Floyd's face floats slightly out of focus/.../ Remember the heat,/ how it burns the back/ Of the throat as night screams his name through the flames."

Of course, Phillips is not saying that everyone must become a poet in order to manage the hell of 2024. Poetry is, of course, a metaphor for a more creative, nuanced form of engagement — for the conversations all three of these poets are midwifing.

Craig Morgan Teicher is the author of several books, including The Trembling Answers, which won the 2018 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets, and the essay collection We Begin in Gladness: How Poets Progress.