Section Branding

Header Content

This medieval astrolabe has both Arabic and Hebrew markings. Here's what it means

Primary Content

Sometimes a little modern technology can help turn up an ancient treasure — even if that technology is nothing more than a computer screen and a simple web search.

That's what happened to Federica Gigante, a historian at the University of Cambridge, who was putting together a lecture about people who collected Islamic art and artifacts. One of those collectors was a 17th-century Italian nobleman from Verona named Ludovico Moscardo.

"I simply Googled his name," recalled Gigante, "thinking, 'I'll stick his portrait on the PowerPoint.'"

Google produced a portrait — but the search also called up a picture of a room from the Museum of the Miniscalchi-Erizzo Foundation in Verona, Italy where that portrait is hanging. And something in this image snagged Gigante's eye.

"I noticed an object on the corner that looked remarkably like an astrolabe," she says.

An astrolabe is a 2D map of the universe, in vogue several hundred years ago. This one consisted of a set of round brass plates, each one not quite the size of a small pizza. Gigante says astrolabes are like the world's earliest smartphones.

"With one simple calculation, you can tell the time," she says. "You can predict at what time sunset will be or sunrise will be." It also lets you compute distances and determine the position of the stars, which could then be used to make horoscopes. (Incidentally, they're also the reason that our watches proceed in the direction we now call 'clockwise' — instead of counter-clockwise.)

Gigante didn't know it then, but the inscriptions of this astrolabe would allow her to chart its journey across two continents during medieval times. And they would reveal an era when Muslims, Jews and Christians built upon one another's intellectual achievements. She published her discovery in the journal Nuncius.

"Astrolabes are a wonderful example demonstrating that knowledge was always in motion, already in pre-modern times," says Petra Schmidl, a historian of science at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg who wasn't involved in the research.

A summer trip to Verona

Back at her computer, Gigante tracked down other photos of the object. "And that's when I got really excited because it was a really remarkable object," she says.

It was covered in Arabic engravings. She deduced it was likely Andalusian — meaning the astrolabe would have been created in southern Spain during medieval times.

As Gigante scrutinized the photos of this astrolabe, she realized that to understand it further — to answer the question of how an astrolabe from 11th century Spain ended up in a museum in 17th century Verona — she simply had to see it up close. So she made her way to Verona last July.

It was a memorable trip: While there, Gigante went to hear opera in the outdoor arena and ate a lot of delicious gelato. But the best part, hands down, was the astrolabe, which was waiting for her at the museum.

"It turned out to be so much more than I had hoped and expected," she says.

First, she saw indications it originated in the 11th century, a time when Spain was under Muslim rule and was one of the world's centers of scientific inquiry and astronomical research.

"Astrolabes were a fairly common tool for scientists besides being used in the community," Gigante explains, "probably in mosques by muezzins to calculate the time of prayer."

To operate an astrolabe, you have to know which latitude you're at. So when Gigante examined an extra brass plate that was added to this astrolabe at a later date and saw that it had a pair of more southern latitudes, it told her that the object had migrated.

"If I had to guess, they're probably Moroccan," she says. "So that means that someone at a certain point of the object's life either needed to travel to North Africa or lived there."

A flash of insight

The room where Gigante was examining the astrolabe had big windows. Sunlight streamed in, illuminating the brass.

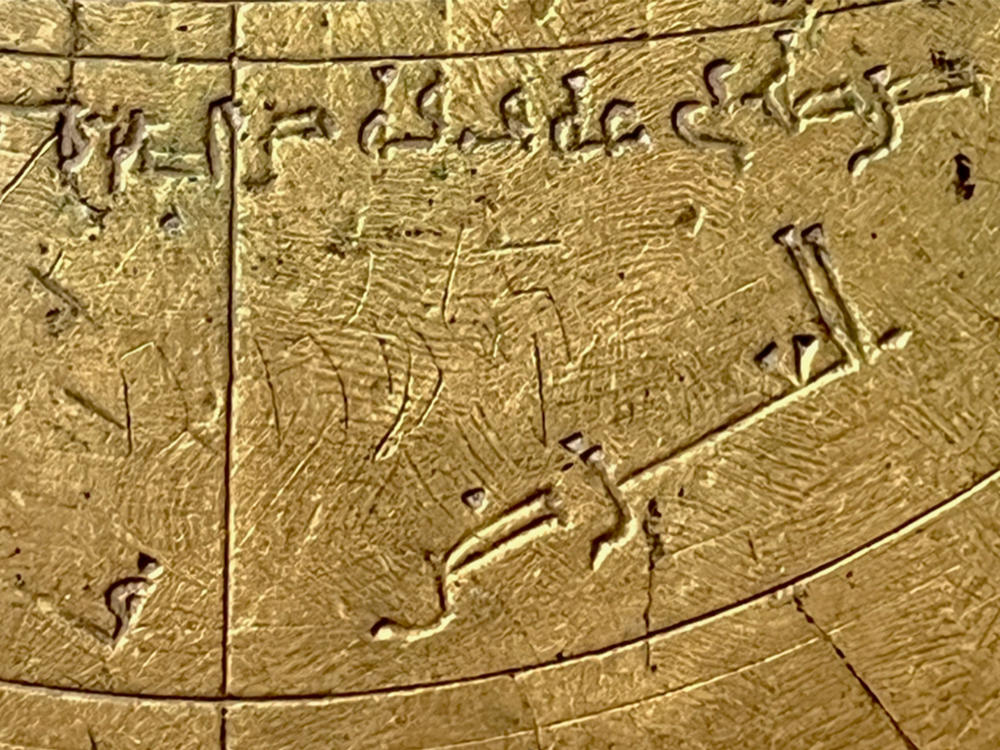

"Suddenly as I moved it around, I could notice some scratches that looked like really intentional markings," she says. "It was only then that I realized that actually these scratches made up letters that weren't even Arabic. They were Hebrew."

These were signatures and translations inscribed by perhaps three different Jewish owners of the astrolabe, says Gigante. It's evidence that the object passed from Muslim to Jewish hands — and that the two groups were living and working alongside one another.

"It reveals the way the object kept on being used in a Jewish community," she says, "despite it being clearly a Muslim object intended for Muslims to serve someone who had to pray five times a day."

Additional markings suggest the astrolabe likely then fell into the hands of a Latin or Italian speaker, finding its way into Ludovico Moscardo's possession, which ultimately became a part of the museum's collection in Verona.

"We can read all of this from the object itself," says Gigante. "It is a testimony of a period of shared existence between Muslim[s] and Jews and Christians who kept on building on each other's knowledge and advancement."

Margaret Gaida, a historian of science at Caltech who wasn't involved in the study, praises Gigante's discovery.

"It's actually really exciting," she says, "because there are very, very few astrolabes that actually have such obvious evidence of cross-cultural interaction. Being able to tie one to a particular place and time is also really challenging. And so the fact that Federica has been able to do that is also really noteworthy."

According to Gaida, astrolabes like this one are important because they reveal a moment when the interactions between Muslims, Jews, and Christians were often constructive, and defined by an exchange of ideas and scholarship.

"These objects remind us that we have a very strong, shared scientific cultural heritage, for one thing," says Gaida. "And for another: that interactions between Jews and Christians and Muslims were defined by respect for each other's intellectual traditions and the authority of those traditions."

In addition, astrolabes help dispel the myth that modern science was born in Europe in isolation. "The contributions of the Islamic world to the field of astronomy are immense," explains Gaida. "And also of the Jewish astronomers working during this time. Many of those texts were then translated into Latin, eventually leading to Copernicus and the scientific revolution."

Gigante agrees. The astrolabe is a Greek invention, "but it was really the Islamic world that perfected it and made it into these extraordinary objects," she says.

Astrolabes allow us to look deeply into these different worlds and times, as we peel back their many layers of history and travel and memory.

"The more you look at one thing, sometimes the more things you see," says Gigante. "And you can read so much of an object if you know where to look."