Caption

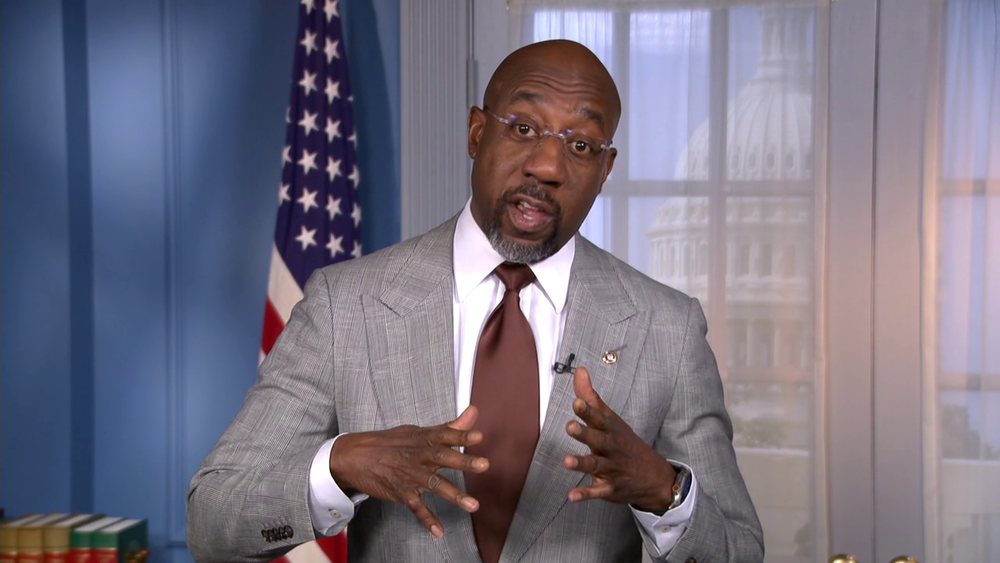

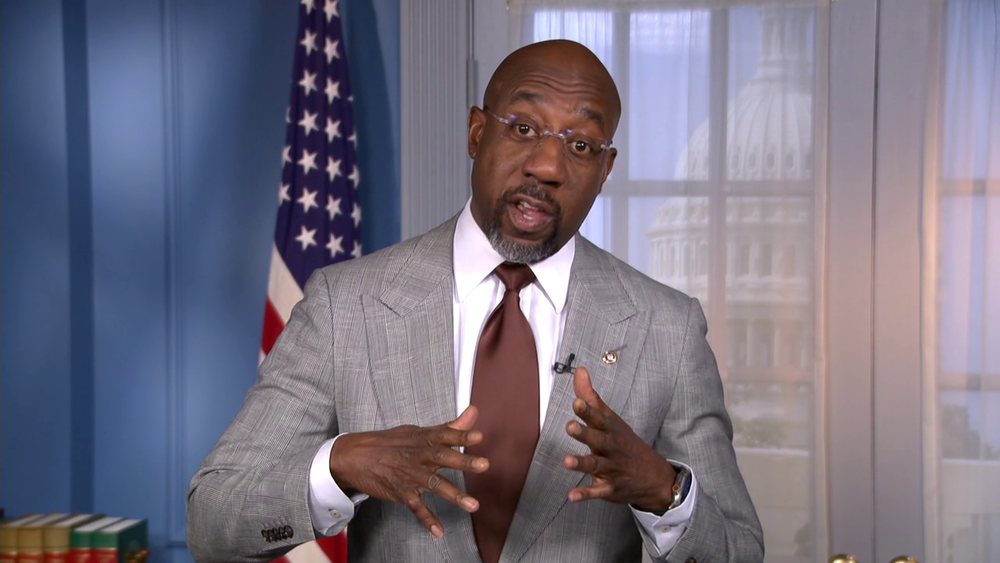

Georgia U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock speaks during a conference call with Savannah-area reporters on March 14, 2024, from Washington, D.C.

Credit: Office of Sen. Raphael Warnock

LISTEN: Sen. Raphael Warnock voiced his support for the potential removal of Savannah's I-16 flyover, which was built in the 1960s and destroyed many Black-owned homes and businesses. GPB's Benjamin Payne reports.

Georgia U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock speaks during a conference call with Savannah-area reporters on March 14, 2024, from Washington, D.C.

Georgia U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock is vowing his support in Congress for the potential removal of Savannah's Interstate 16 flyover, an overpass built in the 1960s over a once-thriving Black business district near where he lived as a child.

Speaking to reporters Thursday about the I-16 flyover project, the Democrat applauded recently announced $1.8 million in federal funding through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and stressed the need to correct what he called a “historic wrong.”

“As a proud native of Savannah who grew up literally in the shadow of this flyover, this project is personal to me,” said Warnock, who was raised in the 1970s and '80s in a public housing complex directly adjacent to the I-16 overpass.

“As a kid who grew up in Kayton Homes, we used to every now and then pass through Frogtown,” Warnock told reporters, referring to a nearby neighborhood. “It was a mystical place for me because it was mostly deserted — and I didn't understand, as a kid, that this was largely a result of this highway that went straight through that community.”

The Interstate 16 flyover crosses Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in Savannah, exiting onto nearby Montgomery Street.

Originally settled by newly emancipated Black residents after the Civil War, Frogtown flourished as a thriving Black business district until the state government — administering federal interstate funding — bore through it to build the flyover.

“A terrible decision was made at a different time in American history,” Warnock said. “People in those communities didn't have a voice, and so they were literally displaced from their businesses and their homes. They reaped the economic consequences of that,” having been “severed from economic mobility and possibility.”

Planning alone for the potential I-16 flyover removal is expected to take multiple years, as the project involves a complex web of local, state and federal transportation officials — a reality which Warnock acknowledged: “We've got a ways to go. Bureaucracy can be slow. But I am, hopeful, that we can get this over the finish line.”