Section Branding

Header Content

Native Hawaiians aim to bring cultural sensitivity to Maui wildfire cleanup

Primary Content

LAHAINA, Hawaii — Mehana Hind stands in the center of a hotel conference room with a wide, welcoming grin.

"Aloha," she says to members of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, newly arrived from the mainland to work on the cleanup of the deadly wildfires that swept Maui last summer. The fires destroyed Lahaina, the one-time capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

"My name is Mehana," she tells the group. "It's a Hawaiian name, means warmth."

Hind is a cultural liaison with the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement. She's here to equip federal cleanup teams to recognize and engage with Lahaina's unique cultural heritage.

"This training is going to have a lot of Hawaiian words," she says. "Let them flow over you."

Hind says the workshop was envisioned about a week after the fires because local leaders recognized that many people would be rotating in and out of Maui to help in the various stages of recovery.

Hind wants the trainees to get comfortable with the local language, with landmarks, and even with staple foods and plants – she shows pictures of them on a large screen behind her.

She encourages them to be mindful of how to pronounce names as a sign of respect to a people who have endured a lot, both through what they've lost in the wildfires, and historically through colonization and ancient Hawaiians' first contact with Europeans.

"We know from our history with contact and with tourism especially, that one of the biggest things that can harm a community that's already been traumatized is cultural differences," Hinds says. "Simple misunderstandings, just because we don't understand each other yet."

Along with this cultural liaison work, several indigenous groups are providing cultural monitors to work alongside the cleanup crews through an $18.7 million contract with the Corps, an effort local residents advocated for after the fires.

"Walk lightly," Hind says. "Know that you are walking in spaces that have created the footprint for some very important things in Hawaii's history."

Significant history lies just below the surface of the ash, she says, getting emotional as she searches for the right way to articulate how sacred Lahaina is to Native Hawaiians: "It's hard to express with any other words than how significant this particular five mile stretch of land is to what Hawaii was, is and can be in the future."

Protecting what lies under the rubble

The historical, archeological, and cultural considerations have led to a deliberate and complicated recovery effort, one without a blueprint.

"This is the most complex disaster that EPA and FEMA has ever dealt with," says Maui Mayor Richard Bissen. "This is not what they normally do.

"In any other debris cleanup situation outside of Hawaii, they would just bulldoze everything from one end of the property to the other, put it in a truck and haul it away."

But in this cleanup, monitors evaluate each individual property for significant artifacts before the site can be cleared of debris.

"They're being very deliberate and delicate with what they're doing," Bissen says.

Patience is wearing thin for some, now seven months after the disaster. To date, about 200 properties have been cleared, out of thousands.

"Moving quickly, moving rapidly is not necessarily the best way to do this work," says Col. Jess Curry, commander of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineer's Recovery Field Office on Maui. He estimates it will be next January before the debris cleanup is complete.

Curry says the cultural considerations here add new layers of complexity to the disaster response — one that's complicated by Native Hawaiians' historical relationship with the federal government.

"As we dig into properties, as we address removing this debris, we are going to take care of things that are important and sacred to this community," Curry says. "And they're going to be right alongside us as we do it, holding us accountable and helping us understand."

An opportunity to find historical and cultural artifacts

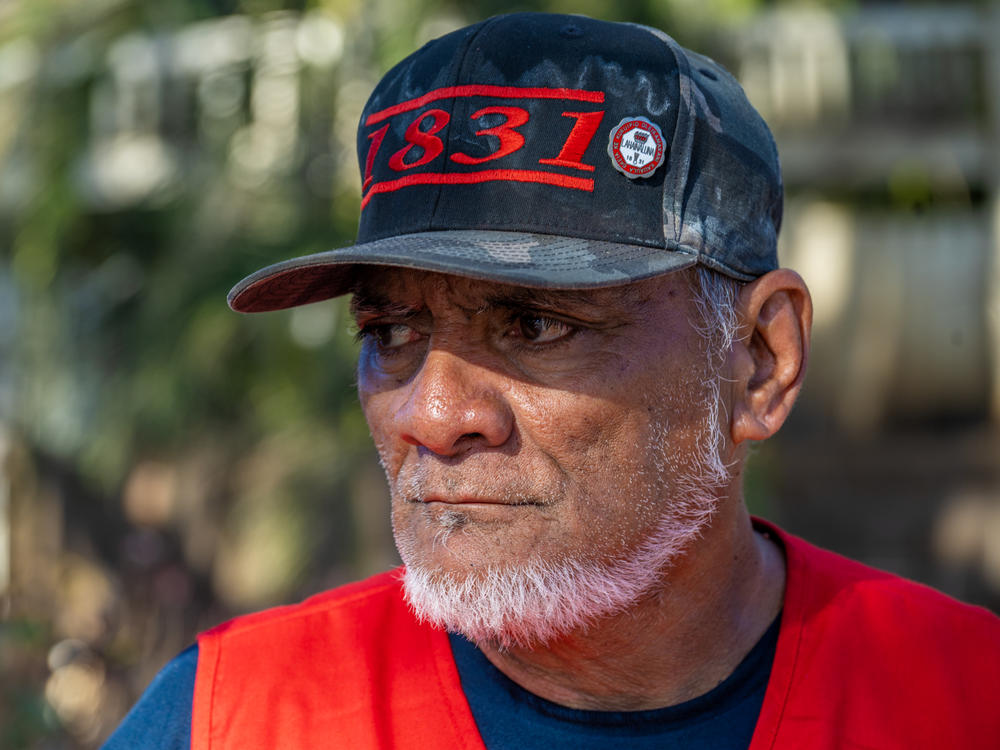

It's about protecting a way of life, says Keeaumoku Kapu, the curator of Na 'Aikane o Maui Cultural Center that burned down in Lahaina.

"There is a consultation that needs to be done to make sure that the people of the land and the history of the land basically isn't erased," Kapu says.

He is also a member of the Maui County Cultural Resources Commission and serves as coordinator of the cultural monitors. Kapu, 60, says 27 generations of his ancestors have lived here.

Kapu still lives on the Kuleana lands that were awarded to his family during the time of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Kuleana means responsibility or privilege in Hawaiian language.

"Lahaina was the Venice of the Pacific during that time," he says with pride. "A lot of sites have been recognized on a national historic registry."

Kapu says about 45 monitors are working in the burn zone along with archeologists, and about a dozen others are on standby should they be needed. They are native Hawaiian people, lineal Lahaina descendants steeped in the history and the culture of the place.

"Now that the town is gone, it gives us an opportunity to start recording and documenting a lot of things that we never saw before," Kapu says.

For instance, the cleanup has revealed original boundaries of properties and ancestral burial grounds. They've already discovered family heirlooms including tools used in the time of pre-contact and poi pounders, stone pestles used to process traditional crops like taro and breadfruit.

Kapu says the cultural teams have been a reassuring presence for people now watching heavy equipment plow through what's left of their homes, treasured family relics, and for some, the remains of loved ones.

"When they see us, it's kind of a sign of relief," he says because they are well known in the community. "We know auntie, we know everybody."

There's a ritual the cultural teams follow each day before work begins, starting with a series of prayers with a rhythmic clap and repeat pattern. Contractors and federal cleanup crews are also invited to participate.

"In order to clean the area, we need to get everybody in sync spiritually, physically and mentally," Kapu says.

They unfurl traditional woven mats that represent the layers of emotion involved in this work and, he says, the secrets hidden within the consecrated ground.

At the end of the day, they gather again in prayer circles. The mats are folded back together to carry the burden of the day.

"We call it kaumaha - weight that we endured throughout the day."

Kapu says it's about grounding themselves for this grueling and haunting work.