GHSA 6A Boys Basketball Championships: Wheeler High School vs Newton High School starts at 7:30 p.m.

Section Branding

Header Content

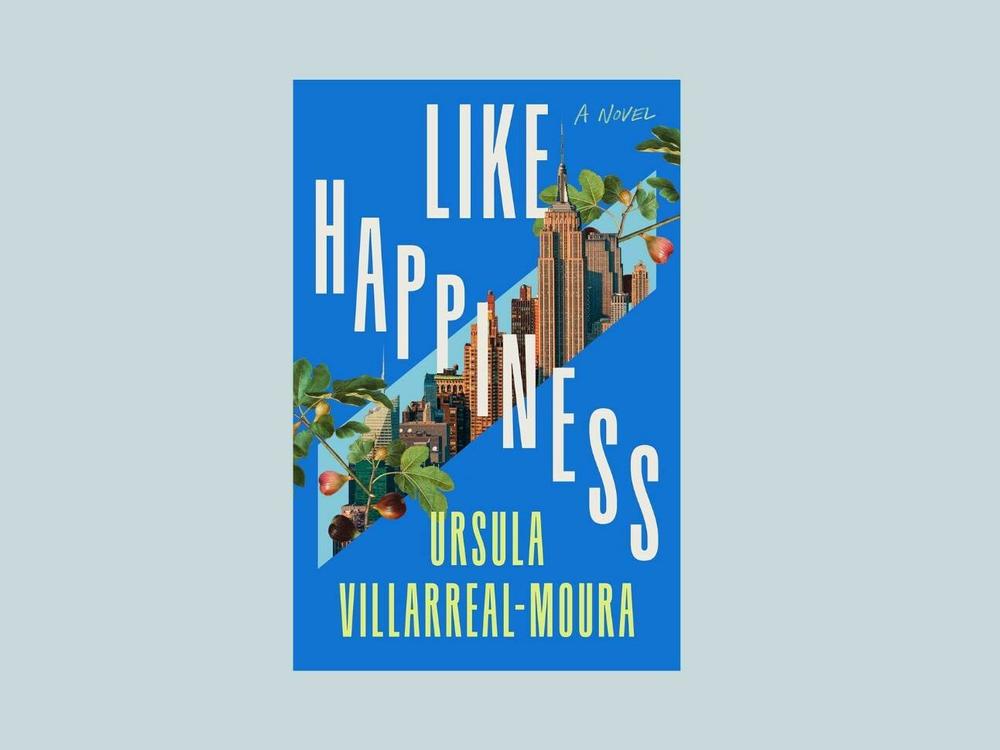

In 'Like Happiness,' a woman struggles to define a past, destructive relationship

Primary Content

When Tatum Vega gets a call from a New York Times journalist asking about famous author M. Domínguez, it's as if a ghost has appeared in the comfortable home she shares with her partner, Vera, in Chile.

Three years have passed since her last interaction with M., whom she had the privilege of knowing as Mateo, and she thought she'd finally shaken off the remnants of their relationship. But when the journalist tells her that a young woman has accused M. of sexual assault, Tatum is both surprised and not. "You weren't that person with me, not exactly," she writes to Mateo, "but the fingerprints of our stories are strikingly similar."

So begins Ursula Villarreal-Moura's debut novel, Like Happiness, which movingly portrays its protagonist coming to terms with the imbalanced, difficult, and sometimes harmful friendship with Mateo that was, at the same time, an essential, and at times euphoric, part of her life for many years.

In short chapters set in Tatum's present-day, 2015, she narrates the process of deciding whether to talk to the NYT journalist investigating Mateo's misdeeds, and how much she should divulge. Most of the novel, however, addresses Mateo directly, as Tatum tries to untangle the story of their decade-long unequal friendship, to understand how early its painful patterns began, and to acknowledge her own role within their dynamic, which kept her trapped within a life smaller than the one she wanted and deserved.

Raised by working-class parents in Texas, Tatum fell in love with books early, finding in them a way to "counter the loneliness and boredom of being an only child." When she goes to Williams College, she feels like she doesn't fit in, believes she might be the only Latina on campus, and admits that in the early days she was "too proud to say that perhaps Massachusetts—home of Plath and Sexton—wasn't for [her]." When, in her senior year, she comes across M. Domínguez's short story collection, Happiness, she's enraptured, and reads it over and over again. Finally, she decides to write to M., care of his publisher. In part, her letter reads: "Although I'm Chicana, not Boricua like you or your characters, I identify with the Latino culture in your work and have found your book to be affirming. It's not often that I see myself reflected in literature, TV, or music... I find your book so indispensable. Your work legitimizes Latino culture and quietly celebrates it. I apologize for placing so much responsibility upon your writing. My intention isn't to overwhelm you, but to thank you."

Unexpectedly, Mateo responds, and soon he and Tatum are exchanging emails, phone calls, and the intimacies of their daily lives, the music they enjoy, the books they revere, and more. Mateo even comes to stay with Tatum on Cape Cod when she gets a housesitting gig there for the summer after she graduates. Is this inappropriate? Tatum is 22 or so at this point, clearly an adult; she knows her own mind and can certainly foster a friendship with an older man if she wishes. But Mateo is 30, a renowned if tokenized author, with more money, power, and status than his young admirer.

Over the course of the following decade, Tatum becomes more and more intertwined with Mateo's life. She travels with him to reading gigs all over the country; she tends to his insecurities and soothes his ego; she nurses both romantic and platonic feelings for him, sometimes reciprocated yet often not; and, perhaps most importantly, she allows her preoccupation with both his brilliance and his confessed brokenness to undermine her own desires, aspirations, and difficulties.

In a 2022 interview with the literary magazine TriQuarterly, Villarreal-Moura said, "Everyone assumes my fiction is autobiographical. That probably has to do with my being a woman. People always assume women are writing about their lives." Back then, Like Happiness had only recently sold, and all potential readers knew then was that it was about a lengthy relationship between a famous Puerto Rican writer and a young Mexican American college student that begins when she writes him a fan letter. Villarreal-Moura shared that based on the mere premise, people began asking whether the novel was autobiographical, to which she replied, "no. It's a product of my imagination."

The author is correct in her assessment that writers who are women and/or queer are far too often assumed to be writing autobiographically. In the case of this novel in particular, however, it's easy to see why some contemporary readers would assume some basis in reality; the story of someone like Mateo taking advantage of younger women is all too common, and various literary luminaries have been accused of abusive behavior during the last decade (and many more are spoken about in the hushed tones and private messages of the whisper network).

Which is to say that while her novel isn't based on anyone in particular, Villarreal-Moura has tapped into something as resonant as it is recognizable, and in Like Happiness has given us a beautiful work of fiction that dwells in the gray areas between celebrity and fan, victim and victimizer, absolution and blame.

Ilana Masad is a fiction writer, book critic, and author of the novel All My Mother's Lovers.

Bottom Content