Section Branding

Header Content

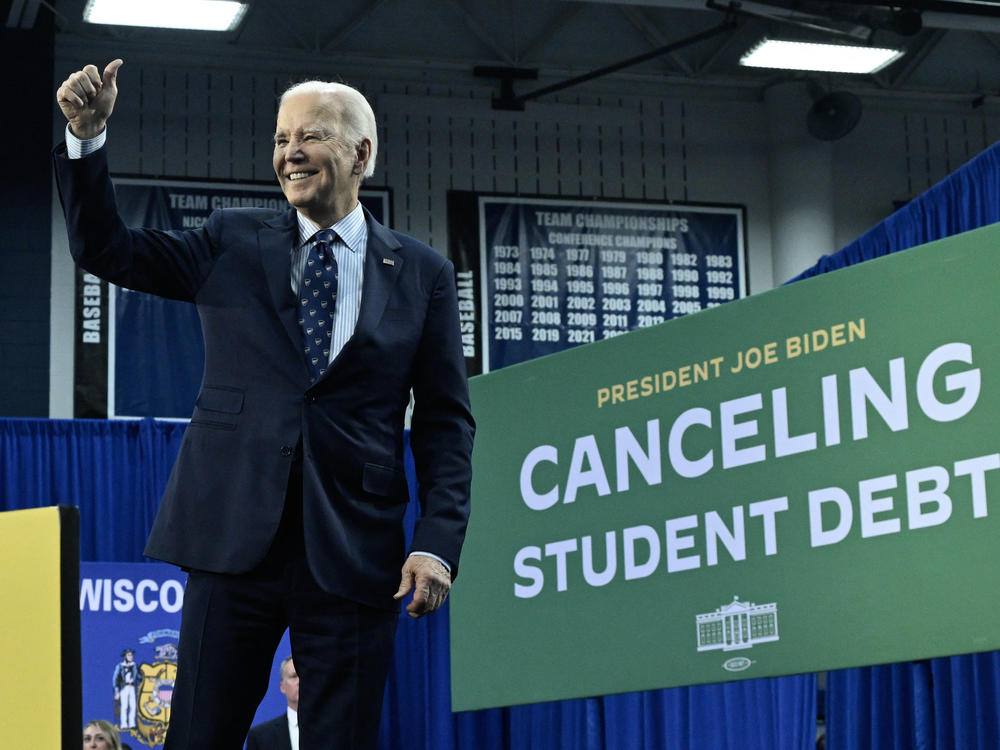

Wisconsin's 'Mad City' is a rational choice for Biden's appeal to youth

Primary Content

This week President Biden took his campaign to save his embattled presidency to Madison, Wisc., the capital of a state he is counting on winning in November.

The capital, sometimes known as "Mad City," is also home to the flagship campus of the University of Wisconsin, the largest college in the state. Beyond the state government and education establishment, Madison has become a magnet for white collar occupations and a hard place for many recent UW graduates to leave.

Given the recent voting proclivities of younger voters and especially those who are current or recent college graduates, Madison and surrounding Dane County should be a trove of votes for Democrats. And indeed, they are.

Historically, Democrats have counted on running up big margins in industrial Milwaukee County, long a stronghold of organized labor and the state's most populous county. Dane and a few other populous counties were counted on in supporting roles. If a Democrat was to win statewide, these polities had to counterbalance the strong Republican leanings of the state's more affluent suburbs and farm towns.

But in recent elections, Dane has stepped out to sing lead. It is the quintessential example of a college-and-government population center that has become more than a trove of Democratic votes. It has become a defining feature of the party identity. It is not much of an exaggeration, if it is one at all, that college towns are to the Democrats today what factory towns were through most of the 20th century.

College towns take the lead

In 2020, for example, Biden carried Milwaukee County by about 183,000 votes over Trump out of about 451,000 votes cast. But he had an almost equal bulge in actual votes in Dane County, where he managed 181,000 votes over Trump out of a far smaller total of about 338,000 votes cast.

In midterm elections, such as 2018 and 2022, the role of Dane County's Democratic turnout has been even more dominant. And the same was true when Wisconsin elected a liberal state supreme court justice in 2023, making it possible to restore abortion rights and throw out Republican-drawn maps for state legislative districts.

So it made sense for Biden to be in Madison if he hopes to keep Wisconsin in his column this fall. And it is hard to overstate the importance of doing so for the president. In 2020 he managed just 49.6 percent of the statewide vote, but it was better than the 46.9 percent Hillary Clinton had in the state in 2016 and just enough to shade then-incumbent President Donald Trump who had 48.9 percent. Trump was only 20,000 votes behind.

Clinton's 2016 loss in Wisconsin had become for some the emblem of her fatal weakness in the Great Lakes region. Michigan and Pennsylvania also fell out of the "Blue Wall" that year after voting Democratic for president every year since 1992 – even when the Democratic candidate was losing nationally.

But somehow Wisconsin seemed the unkindest cut of all. Polls there had shown Clinton's lead well beyond the margin of error. And Wisconsin had been voting Democratic even longer than the others, all the way back to 1988. Confident of Wisconsin, the Clinton campaign did not return for events in the state after the primary.

So this past week Biden was wooing Wisconsin, but also pitching a more specific target just as crucial to his reelection. He was not only speaking in a college town, he was speaking directly to current and recent students. And he brought some beef in his message, promising a renewed push to grant student debt relief in the billions of dollars.

Pandering or just politics?

The promise of such generous student debt relief was dismissed as pandering by some, but in politics there are rarely any points given for subtlety. And before the week was over, Biden was reaching out to the same general demographic target. He promised to close the "gun show loophole" by which thousands of guns each year by people who do not undergo background checks before selling the weapons.

Biden wants gun control supporters' votes wherever he can find them, of course, but here too younger voters are seen as the key. Gun control ranks just below abortion rights on the list of issues motivating younger potential Democratic voters.

So far, of course, both these Biden initiatives count as virtue signaling more than actual policy making. The debt relief proposal will need to survive court tests, and an earlier Biden effort to cancel debt was spiked by the Supreme Court when the justices decided it needed congressional approval. The gun control measure will also confront Republican resistance and still more tests in federal courts.

But the appeal of student debt relief goes beyond the dollar value itself. It represents the freedom to chart their own direction after college for millions of current or recent students. In that respect it is similar to the ending of the military draft in the 1970s, which freed millions of young men from conscription and contributed to President Richard Nixon's improved showing among younger voters in his landslide 1972 re-election.

And gun control has an emotional potential that has had electoral impact in the past, at least in the media and at least in the wake of major mass shootings.

Critical parts of coalition

The Biden camp regards younger voters in general and college students in particular to be critical parts of its coalition nationwide, but especially in swing states.

The Pew Research Center studied survey research results from nearly 12,000 voters whose participation in 2020 was confirmed against registration rolls. The results showed voters under 30 favored Biden over Trump by about 20 points. It was by far his best showing in any age group and notable indeed for the oldest candidate for president ever nominated by a major party. But recent polls of the 2024 Biden-Trump rematch show serious erosion in that dominance.

The day before Biden landed in Madison, Politico was publishing a piece by reporter Steven Shepard on 2024 polls that showed Biden trending down among the young but getting a bit stronger among the old – at least relative to previous Democratic nominees (including himself).

Shepard noted what a reversal this would be from longtime presumptions about the votes of various age groups. He even suggested there could be a problem with the polls themselves. It is also possible that some young people are leaning toward Trump, or at least away from Biden, to show their displeasure with the Democrats' handling of various issues.

Many activists are distressed at the gradual approach Biden has taken to their issue, be it climate change or gun control or income inequality. Many think he has overcommitted the U.S. to supporting Israel in its war against Hamas.

Of course, not all younger voters are activists committed to these issues. And not all have student debt to be cancelled. The one thing young voters all do have in common is the burden of economic conditions such as inflation. After all, the bout of inflation the U.S. has suffered in the Biden years is younger voters' first experience of that disheartening economic hardship. The last time inflation was really a voting issue was a generation ago.

This week, Christian Paz of Vox looked at various 2024 polls released in the past three months. In March 2024 polls alone, Paz wrote, there was "a shift from 2020 among adults under 30 of about 13 points toward Trump, even though Biden still holds an overall advantage [in the demographic] of 11 points in the aggregate."

Those numbers were no doubt part of the calculus for Biden's current outreach to younger voters. His trip to Madison was not only sending a signal to younger voters nationwide but responding to the signals he and his campaign have been getting from them.

Biden likes to call college "a ticket to the middle class." And the recent emphasis on lowering educational barriers and boosting educational borrowers may well reinforce the impression that Democrats mostly care about the educated. That is an argument Republicans are sure to make and stress.

Moreover, even as college towns have emerged as the new base of the Democratic Party, some elements of the workforce and the culture may be forsaking the college paradigm. Campus enrollment numbers have yet to return to pre-pandemic levels. One study measured a drop in total undergraduate enrollment of nearly 6% between the fall of 2019 and the fall of 2023. And there are signs that may well continue.

The Wall Street Journal this month reported on Gen Z becoming "the tool belt generation," noting its increased interest in skilled trades such as welding and other wage earning occupations. And the resurgence of union organizing and collective bargaining has revived a once common trajectory to a comfortable middle-class life.

Democrats had shifted away from their heavy dependence on unions in recent decades, but Biden and others have worked to keep those lines of connection active, strongly backing the efforts of the UAW and others.

That may serve the party well as a retro strategy if indeed the U.S. has passed through its "peak college" phase and graduated into a new era.