GHSA 6A Boys Basketball Championships: Wheeler High School vs Newton High School starts at 7:30 p.m.

Section Branding

Header Content

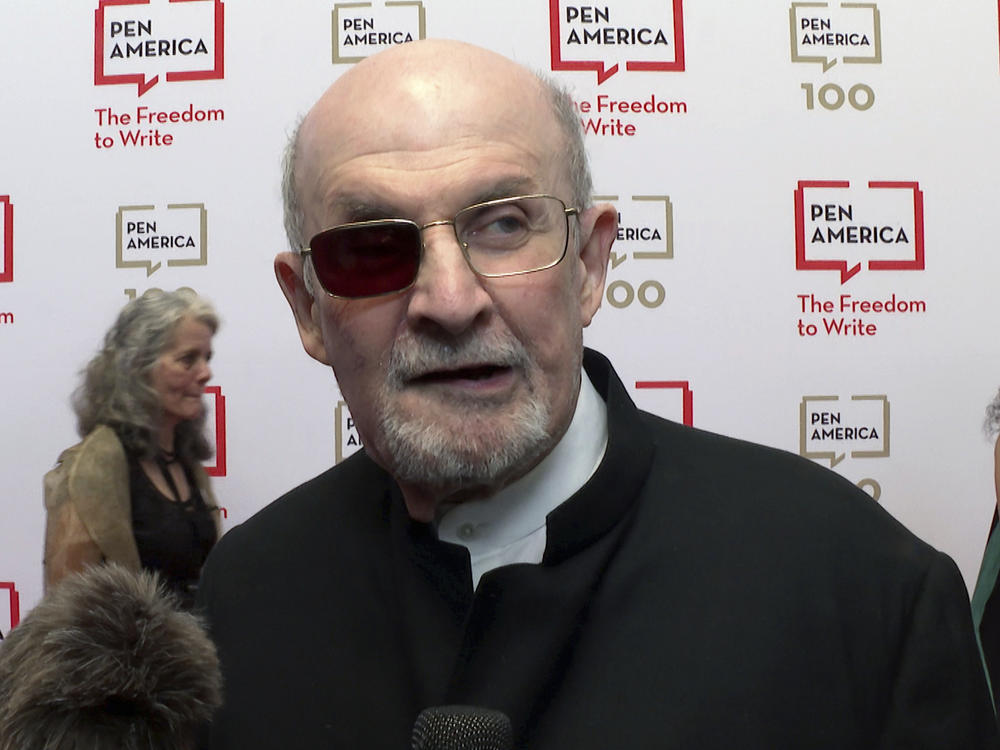

5 takeaways from Salman Rushdie's new memoir 'Knife'

Primary Content

On August 12, 2022, famed author Salman Rushdie was stabbed. He was on stage at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York, about to give a talk "about the importance of keeping writers safe from harm," Rushdie writes in his new memoir, Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder.

Rushdie, the 76-year-old writer of The Satanic Verses, Midnight's Children, Victory City, and more, survived the attack. But not without some lasting scars, including being blind in one eye. Since the attack, he's done a handful of interviews here and there, but he's kept mostly to himself. In Knife, he details everything that's been going on in his life and in his head since the attack. He talks about the recovery process, the support he received from loved ones, and his feelings about his alleged attacker, Hadi Matar.

Matar is in custody at Chautauqua County Jail, being charged with second-degree attempted murder and second-degree assault. The judge in his case actually postponed Matar's trial after Rushdie announced his memoir, in order to give Matar's lawyers an opportunity to see what's inside the book.

The book is out Tuesday. Here's what you can expect from it:

1. Rushdie has no interest in re-litigating The Satanic Verses

Rushdie only makes a few mentions of his 1988 book that led the supreme leader of Iran at the time to call for Rushdie's death. And, Rushdie notes in Knife, it wasn't just the Muslim world criticizing Rushdie for writing the book. He calls out other names, including former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and the writers Roald Dahl and Germaine Greer. Besides that, Rushdie writes that he's said everything he's needed to say about Satanic Verses in his previous memoir, Joseph Anton." If anyone's looking for remorse, you can stop reading right here," he writes in Knife. "My novels can take care of themselves."

2. The book is about freedom of speech, particularly aimed at the left

Rushdie instead saves his argumentative energy to make an appeal for freedom of speech – an ideal, he believes, progressives and the left have left behind to their detriment. "This move away from First Amendment principles allowed that venerable piece of Constitution to be co-opted by the right," he writes. Rushdie had a long background in free speech advocacy. He's the former president of PEN America, the literary rights advocacy group, and co-founded that organization's World Voices Festival. His first public appearance after being attacked was at a PEN Gala in his honor. And, if anything, the attack has only furthered his positions. "Art is not a luxury. It stands at the essence of our humanity, and it asks for no special protection except the right to exist," he writes.

3. It's also a book about marriage

In 2021, Rushdie quietly married the poet and novelist Rachel Eliza Griffiths. Rushdie is tender when he writes about the early days of their relationship, saying he was not looking for romance. "And then it came up behind me and whacked me behind the ear and I was powerless to resist."

It's Griffiths who helps Rushdie through the many doctor visits, physical therapy appointments, sleepless nights, mystery ailments and piling bills (a sub-takeaway could be, not even world-famous authors can avoid surprise medical bills), all while tending to her own writing career. There are tough moments that they have to go through together in the book, but there are also regular moments that could be scenes from any other marriage.

4. He tries to understand his attacker

Rushdie never refers to Matar by name in the book. And he maintains a certain distance from him. There's a quick instance in the memoir where Rushdie toys with the idea of reaching out to Matar, but he quickly decides that's a bad idea. Instead, Rushdie chooses a different route to understanding Matar that we won't spoil here. But it is an exercise in deep empathy – one that seems to help Rushdie find at least a little bit of closure.

5. There's a possible documentary on the way.

Early on in the book, Rushdie and Griffiths begin filming Rushdie's thoughts. The plan seems to be to take all the footage and bring it to an experienced filmmaker, who can shape it into something. But there have been no announcements made on that front yet.

Bottom Content