Section Branding

Header Content

Top companies are on students' divest list. But does it really work?

Primary Content

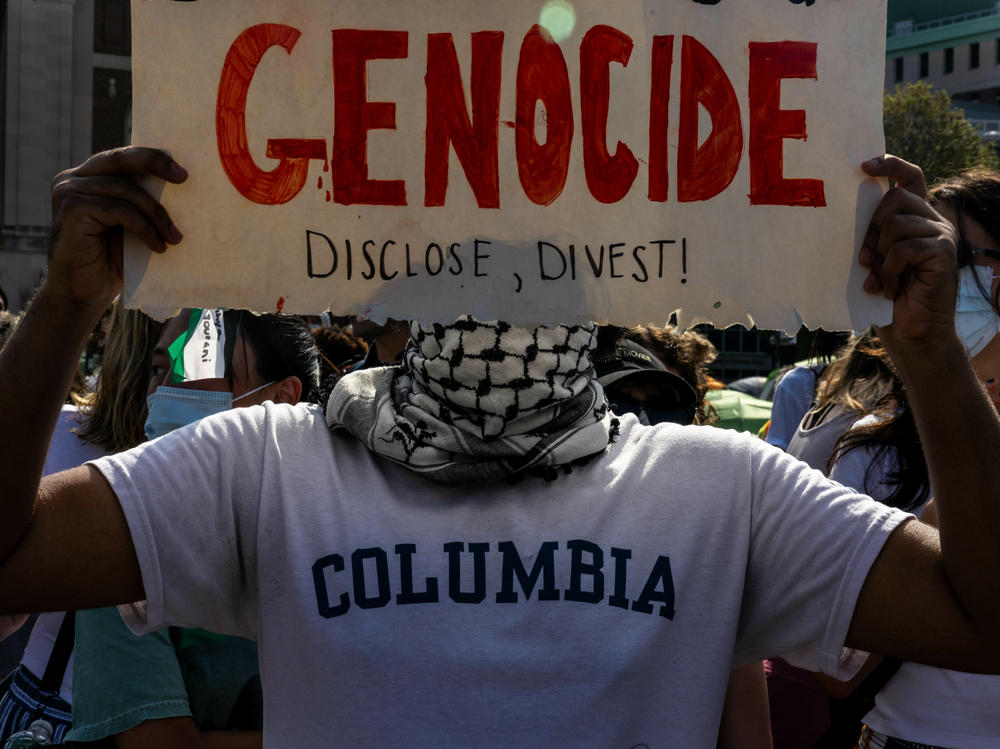

It's become a common mantra by protesters at universities across the country: "Disclose, divest, we will not stop, we will not rest."

Broadly, the protesters want their universities to sell off their investments in companies that have businesses or investments in Israel because of the country's invasion of Gaza. That's where the term divest comes from.

The calls on campuses vary. Columbia University protesters, for example, have a broad list of divestment targets, demanding the Ivy League college disclose and unload investments in a broad set of companies with ties to Israel, including Google, Amazon and Airbnb.

Other protesters at universities are targeting defense-related companies and weapon manufacturers. Cornell University protesters are calling for divestments from companies including Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

Here's a look at what divestment means.

Why there's a call for divestments

Protests against university investments have a long history.

During the 1970s and 1980s, students at Columbia and other universities successfully pressed administrators to sell off investments in companies doing business with South Africa over the country's apartheid policies.

Since the 2010s, students have successfully called for some universities to divest themselves from companies tied to fossil fuels or to freeze their investments in that sector, including at Syracuse University.

Do divestments actually work?

Not really. Divesting by universities doesn't change corporate behavior, but it can provide a big moral and symbolic victory for protesters.

Most analysts agree that divestments don't usually punish the companies targeted. And some analysts argue divestments actually are worse in the long run. By staying invested, the reasoning goes, universities can have more of a say about a company's operations. Selling off their investments would likely be scooped up by other investors who are less likely to speak up.

For universities, divesting from companies that do business in Israel could also risk blowback from students, faculty or alumni who support Israel.

The University of California, for example, said it was opposed to "calls for boycott against and divestments from Israel."

"While the University affirms the right of our community members to express diverse viewpoints, a boycott of this sort impinges on the academic freedom of our students and faculty and the unfettered exchange of ideas on our campuses" the university said last week.

These are big reasons why almost no university has yet agreed to divest from investments tied to Israel, though a few have been willing to hold talks with protesters.

Protesters are pressing on, however. That's because getting a university to divest from companies with ties to Israel would not only achieve their goals, it would also likely serve as a moral victory by sparking a lot of headlines and debate.

"Divestment itself doesn't really influence the companies or the industries being targeted directly," said Prof. Todd Ely from the School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado Denver. "It's more the stigma created and drawing attention to the issue more broadly."

Can universities actually do it?

Yes, but it can be complicated.

Endowments at the nation's top universities have grown into multi-billion dollar chests, with investments in all kind of investment funds, including specialized private funds that prevent people from cashing out for a number of years.

More broadly, endowments have become a vital source of financing for universities. They allow for investments and scholarships while securing the university's financial future.

Some endowment chiefs have even become well known figures in finance, including the late David Swensen who served as Yale's chief investment officer and grew the university's funds massively.

Endowments "are intended to kind of preserve and grow the resources available to colleges and universities. And the number one use of those funds is to support students and student financial aid," says Prof. Ely. "So it's a complex situation where calls to change the way these funds are invested by students and other interested parties do end up kind of in a circular way going back to support the students themselves."