Caption

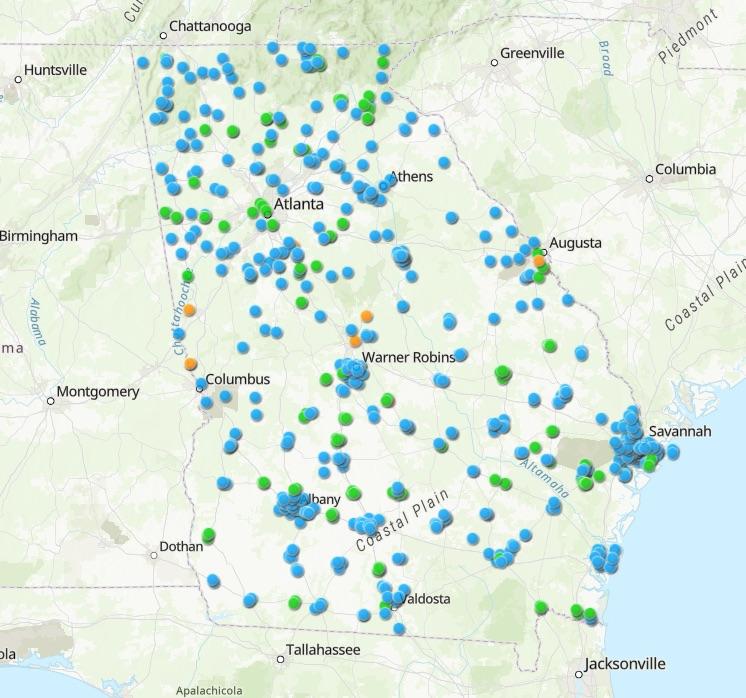

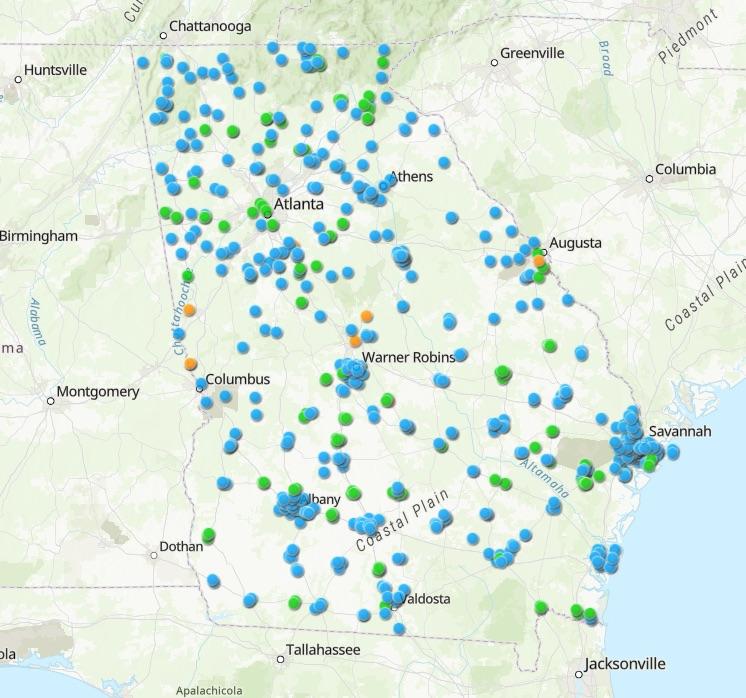

Blue dots indicate sites to be tested for PFAS in water supply. Green indicates tested locations with acceptable levels of PFAS. Orange indicates unacceptable levels found.

Credit: Georgia EPD screenshot

Blue dots indicate sites to be tested for PFAS in water supply. Green indicates tested locations with acceptable levels of PFAS. Orange indicates unacceptable levels found.

Mary Landers, The Current

Even before EPA issued the first ever drinking water standards for PFAS chemicals last month, state and local water officials in Coastal Georgia were monitoring for and making plans to address these “forever chemicals.”

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. They are a category of chemicals whose strong chemicals bonds make them useful in products ranging from nonstick cookware to firefighting foam. Research indicates long-term exposure to certain PFAS can cause cancer and other illnesses.

Georgia regulators began assessing the level of PFAS in water supplies and drinking water across the state in 2013. In the monitoring survey conducted from 2021-2023, none of the dozens of sites tested in coastal counties showed PFAS levels at or above the reporting limit of 4 parts per trillion.

The Georgia Environmental Protection Division publishes results online at its PFAS story map. The current testing, expected to be complete by December 2025, is looking for the presence of 29 PFAS substances. So far, no coastal sites have shown PFAS above the reporting limit in EPD’s testing.

“EPD will keep updating the map as and when the data becomes available,” Spokeswoman Sara Lips wrote in an email. “Generally, EPD releases the data once a quarter, so the data will be updated quarterly.”

Statewide, EPD has found PFAS in surface water as well as groundwater systems.

“These wells (with elevated PFAS levels) are typically located along the fault lines or in areas where the groundwater is more susceptible to be contaminated,” Lips wrote.

Groundwater in the coastal areas appears to be PFAS free in testing so far, but that might not always be the case, Lips warned.

“The ones that we sampled and tested did not show any contamination. But we did not test all the water systems around the coast and there are some areas along the coast that are susceptible to ground water contamination.”

Savannah, the largest municipal supplier of drinking water on the coast, posts its PFAS information online here. Savannah draws water both from wells and from a tributary of the Savannah River.

“Like many water utilities along the Savannah River and elsewhere around the country, the City of Savannah’s surface water is affected by PFAS,” the site states. “For Savannah, the levels of PFOA and PFOS in the water that will withdraw from the Savannah River are near the USEPA proposed Maximum Contaminant Level of 4.0 parts per trillion (ppt).”

The city lists samples exceeding the 4 ppt mark on three of five testing dates, though the average of the five samples was below the limit.

Savannah plans to include PFAS filtering in a planned expansion of its Industrial & Domestic drinking water plant, which processes water drawn from Abercorn Creek, Savannah Water Resources Director Ron Feldner told the Garden City City Council at its workshop Monday. (Savannah currently sells drinking water to Garden City and Feldner attended the meeting to present options for reworking those agreements.)

“Actually, compared to a lot of water systems around the state we are in very good shape,” Feldner told the Garden City City Council Monday.

Beginning in 2029, public water systems that have PFAS in drinking water above established limits must take action to reduce levels of these PFAS in their drinking water and must provide notification to the public of the violation.

City staff are currently reviewing the new PFAS drinking water regulations.

“Once a full evaluation is made, staff will share details of the City’s plan with the public,” city spokesman Josh Peacock wrote in an email statement.

While drinking water is the focus of the EPA regulations finalized in April, Ogeechee Riverkeeper Damon Mullis recently went to Washington, D.C., with other environmental activists to remind lawmakers about other ways people might be exposed to PFAS.

Ogeechee Riverkeeper Damon Mullis poses in front of the EPA building on a recent trip to discuss PFAS.

“Don’t forget that that drinking water is only one pathway for PFAS to find people,” he said in an interview with The Current. “So we have the food supply also. And fish tissue is obviously very important for that plus, you know, all these rivers empty into the estuaries, and so there could potentially be seafood implications.”

The Ogeechee Riverkeeper documented PFAS in the Ogeechee in 2020, and shared evidence to indicating these chemicals were being discharged by the Milliken textile treatment facility (formerly King America Finishing) in Screven County. Milliken later agreed to stop using PFAS. The plant announced its closure in 2022 and is now in the process of shutting down.

Sewage sludge is also prone to PFAS contamination, Mullis said.

“So there’s a lot of wastewater treatment plants that take municipal sewage, but also industrial waste,” Mullis said. “And then that sludge is used for fertilizer. For instance, in our basin at times, we’ve had hay fields up in the northern part of the basin that were being fertilized from Messerly (Water Pollution Control Plant) out of Augusta, which takes a lot of industrial waste. And so we’re concerned about that.”

PFAS are a bigger concern to human health than to ecological health at the moment, Mullis said.

“But as we learn more, and as these chemicals stay in the environment for a very long time, that probably will start to change,” Mullis said.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.