Section Branding

Header Content

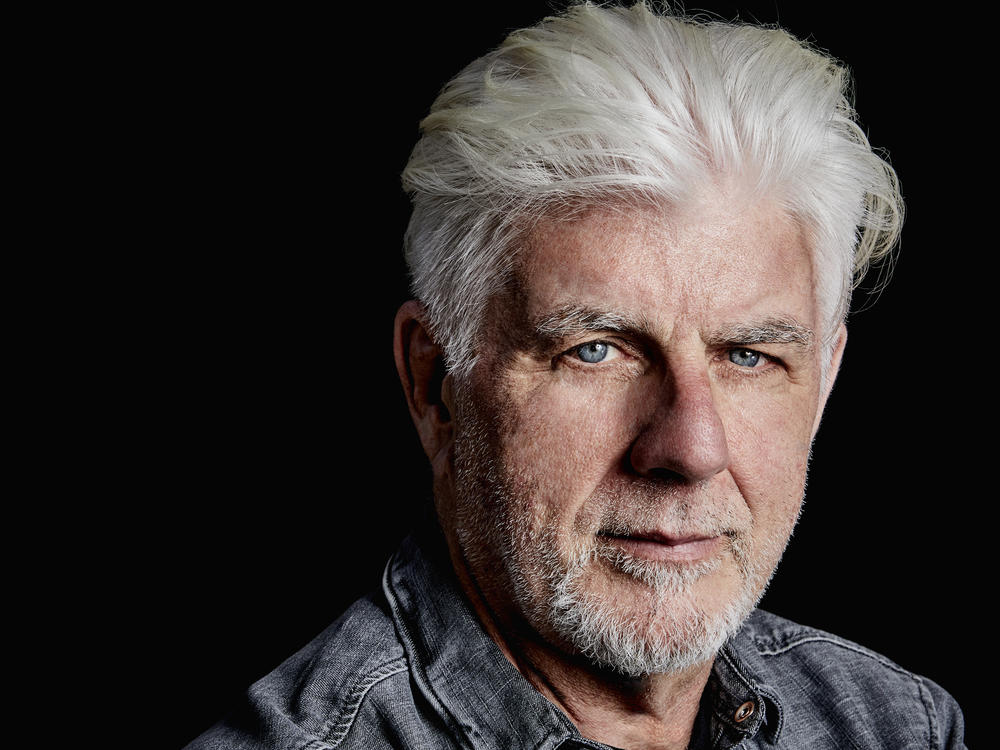

With age and sobriety, Michael McDonald is ready to get personal

Primary Content

Even Grammy Award-winning singer/songwriter Michael McDonald says he feels like an imposter sometimes.

"I don't mean to be self-deprecating when I say this, but I never really understood why people gave me so much credit as a musician," McDonald says. "I really am just, more or less, a songwriter who plays a little bit of piano."

It's an understatement. McDonald's singular sound that has captivated audiences for generations and has given life to remixes, remakes and thousands of impressions from Tonight Show skits to The Voice.

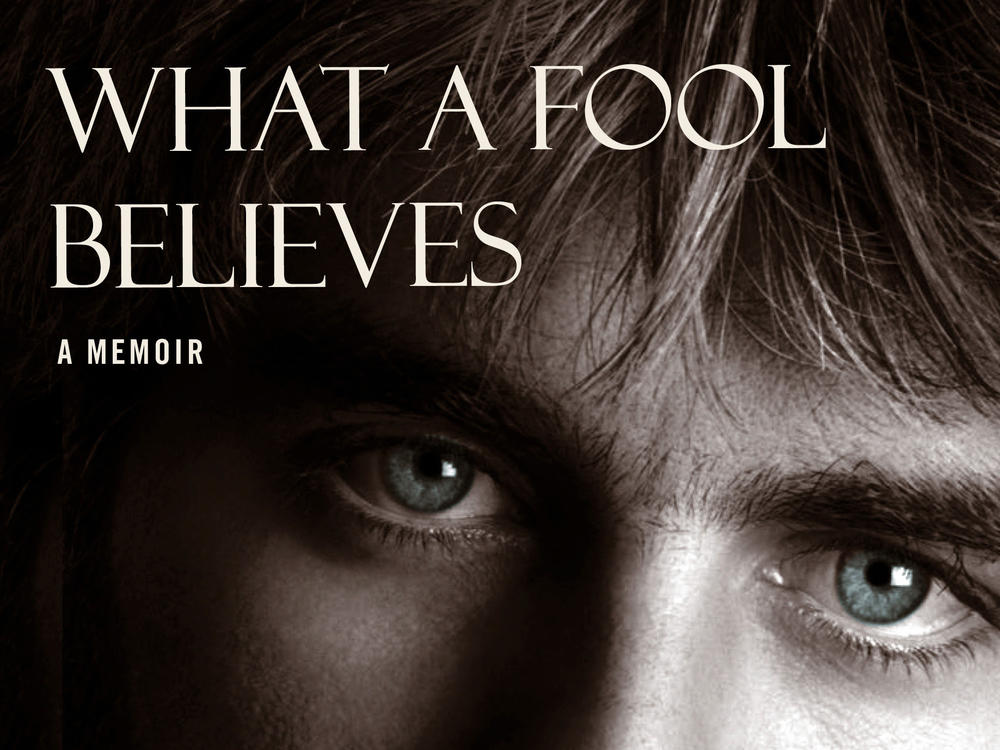

His new memoir, What A Fool Believes, which he co-wrote with comedian Paul Reiser, chronicles McDonald's childhood in Ferguson, MO., his early years as a session musician and his decades-long career as a member of Steely Dan and The Doobie Brothers and as a solo artist.

Throughout his career, McDonald was known for crossover hits. His 1982 single, "I Keep Forgettin'," cracked the top 10 of Billboard's Pop, R&B and Adult Contemporary charts, and was later sampled by hip-hop artists Warren G and Nate Dogg in their 1994 hit, "Regulate."

McDonald says that earlier in his career, he tended to avoid writing about himself directly in songs. But looking back now, he's noticed a shift in his music, which he attributes, in part, to becoming sober in the mid 1980s.

"More than anything, I think what people who suffer from addiction share universally is that we're kind of hiding from ourselves. We're kind of hiding from our feelings," he says. "I've learned in sobriety to slowly peel back different layers."

Interview highlights

On his first band, Mike and the Majestics

It was Mike and the Majestics, and I soon got demoted, and it was just the Majestics. We started when we were all around 12. I think our first gigs happened more like when I was 13. And the other guys were a year and two older than me.

Back then, we were playing basement parties, birthday parties for girls we knew in the eighth grade. And then we graduated to fraternity parties, at a very tender age, which my mother was not happy about. And so she enlisted my father to come on as our manager — not before we were exposed to some of the rites of passage that we were probably too young to witness. ... We thought we'd died and gone to heaven. Because the girls were all really cute, and the frat guys were out of their minds and they would pass the hat. ... But then we had a curfew because we were all like 12 and 13 years old. And in the course of all this, we learned all the filthy lyrics to "Louie Louie" and songs like that were college staples.

On writing the Doobie Brothers' song, "Takin' It To The Streets," which was inspired by gospel

The intro of the song just kind of popped in my head, and I couldn't wait to get to the gig and set my piano up and pick the chords out on the piano. ... It just felt like an opening to a gospel song and I loved gospel music at the time. ... What better motif for that very idea of people falling through the cracks of our society and ... and how do we do better by each other than a gospel song. ... It took me a minute to come up with "Takin' to the Streets" because that came from the idea that ... we've got to do better by each other or this is what it's going to come to. It's going to be settled one way or the other. These kinds of progressive ideas and reforms don't come easily, and they come by necessity. ... We're going to meet on the same plane one way or the other, maybe we can do it out of love for each other and consideration and empathy before we have to do it out of frustration.

On the realization that white artists were covering Black musicians' songs and being praised for it

I think that was pretty much the experience of a lot of people in my generation growing up. White kids who thought that Pat Boone wrote, "Tutti Frutti." We didn't know any better, you know, because radio was so segregated, as was everything, in the United States at the time. It was a sad division in what really was such a strong part of our culture, you know, but it was always kind of isolated away from and giving credit to the people who really brought those art forms to America and, really gave America its own true artistic art form: Jazz and R&B music and gospel. ...

For instance, the English invasion bands, we thought that they wrote those songs like, "It's All Over Now" by The Rolling Stones was Bobby Womack and his brothers and had a group called The Valentinos, and that song was a No. 1 hit on Black radio when the Stones released it. ... I never cease to be surprised by the roots of some music that I thought was more of a pop record, but that really has its roots in the blues tradition and was written by American artists who didn't really enjoy the success of the song that other artists did.

On being big in the Black community

Whenever that was brought to my attention, by friends of mine who liked our music, I was really flattered by that. And I continue to be flattered because, to me, that's really the test of anything I ever really desired to do was to represent, in my own way, what I truly believe is American music. To have that privilege of being able to do that and have it accepted by the audience who I believe created it, who invented it and brought it to all of us.

On how his voice has aged

The voice is a malleable instrument, at best, and especially with age, it's like you're constantly renegotiating with it. I find that at my age now, I'm just trying to figure out what my strengths are and what I can use to put the song across. I wish in some ways I could sing with the range or the sense of pitch or whatever it is I had when I was younger. But unfortunately, those things change over the years. ...

I've been less reluctant to lower keys and stuff, and especially if it brings a better performance out of me, but I found that a lot of things have changed. ... I have to kind of learn what still works for me when I'm singing, because I don't want to be trying to sound like I used to sound and have that be obvious. I want to just be able to do what I do best now.

Sam Briger and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.