Caption

Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge features live oak trees draped with Spanish moss, as pictured here on the north side of the peninsula, as well as saltmarsh, pine forests and shrublands.

Credit: Benjamin Payne / GPB News

LISTEN: A grassroots campaign is underway to reclaim ancestral Black land on the peninsula of Harris Neck in McIntosh County. GPB's Benjamin Payne reports.

Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge features live oak trees draped with Spanish moss, as pictured here on the north side of the peninsula, as well as saltmarsh, pine forests and shrublands.

Standing quietly next to a still pond, Wilson Moran remembers the stories his mother would recount about her idyllic childhood spent along these banks.

The water's edge is now encrusted with a thick layer of algae. But back when Mary Moran was a girl in the 1930s, it sparkled with a different shade of green.

“My mother told me the major problem she had with growing the rice was the rice birds,” the 81-year-old said with a soft chuckle. “She'd be walking through the paddies, banging metal pans or whatever to keep the rice birds from eating all the rice.”

His voice trails off wistfully.

“But, like my mother would tell you,” he continued, “she lived here for 20 years — and the best years of her life was right here.”

Here is Harris Neck, a 2,824-acre peninsula just off Georgia's Atlantic coast — in rural McIntosh County, about 30 miles south of Savannah — which was long home to Gullah Geechee people from West Africa, first as enslaved workers, and later as landowners after their emancipation through the Civil War.

During World War II, though, the federal government forced these Black residents — including Mary Moran, while she was pregnant with Wilson — off their land via eminent domain to build an auxiliary airbase.

The land was never returned to the dispossessed families, despite promises that it would eventually be handed back.

Instead, it was transferred to power brokers within the government of majority-white McIntosh County, who — after “years of local mismanagement,” according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — relinquished the land back to the federal government, which established it as a national wildlife refuge in 1962.

Now, descendants through the Harris Neck Land Trust, of which Moran is a leading figure and board member, intend to ask President Joe Biden for an executive order this summer to return 500 acres on Harris Neck — approximately 17% of the refuge's total acreage — to the nonprofit organization.

Their planned trip to Washington, D.C., which GPB is the first to report, comes after years of fruitless efforts by the group to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service — the Interior Department agency which oversees the refuge — as well as with Congress.

“There was a moral injustice done to those 75 to 80 families that lived on Harris Neck,” said descendant and Harris Neck Land Trust chairman Winston Relaford. “All we're asking the federal government to do is just grow a backbone, stand up with some courage and correct a moral wrong.”

The group's executive director, Dave Kelly, said that the organization currently has representatives from 69 descendant families, and maintains that the federal government violated “almost every element” of eminent domain in its wartime proceedings, including barring Black landowners from hiring independent appraisers.

“If somebody gives you a price, you don't just take it,” said Kelly, adding that Black families were given only a fraction of the compensation that white landowners elsewhere in the U.S. received during wartime takeovers.

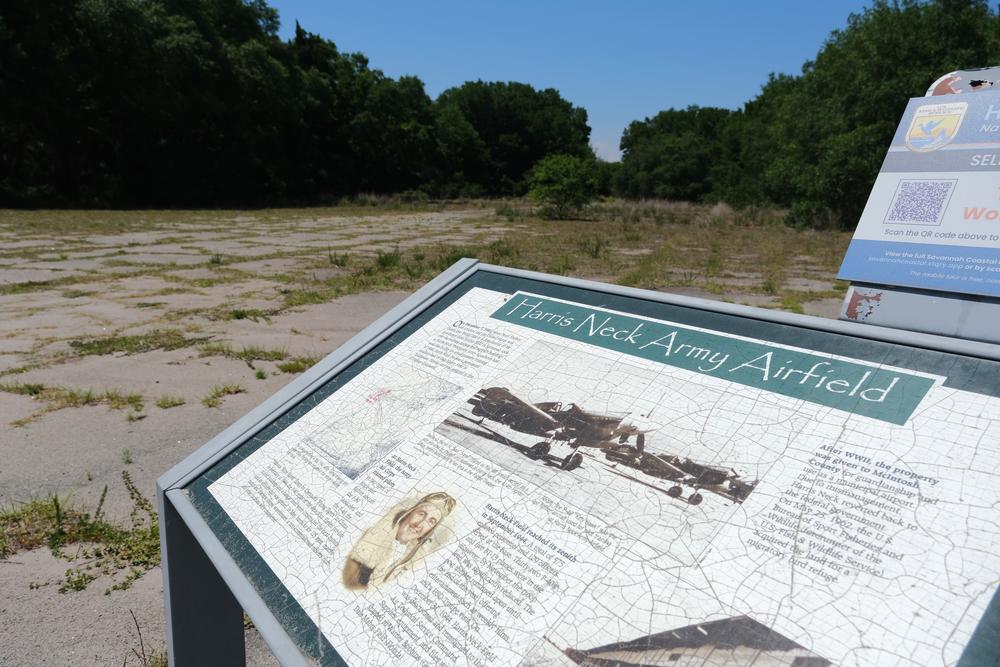

A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service interpretive sign at the site of the former Harris Neck Army Airfield gives a timeline of the military installation, without mentioning the federal government's takeover of Harris Neck through eminent domain.

“When it came to a Black man in 1942, what recourse did he have?” Relaford said. “You know, he had to agree. He had no basis to fight from, you might say. So, the land was given.”

90% of the requested 500 acres would remain as greenspace, Kelly said, with the remaining 10% allocated for cultural institutions — including a “living museum” transporting visitors back to what Harris Neck looked like in 1900 — and residential lots for descendant families to build homes.

Kelly says that the group's sought-after acreage is located far away from the refuge's federally protected wood stork habitat; rather, it's on what he calls poorly managed forestland — “a wildfire waiting to happen,” as Kelly put it.

The Fish and Wildlife Service declined GPB's request for an interview, after a spokesperson initially wrote in an email that the agency would “work to assure that we have the correct subject matter expert available for interview.”

Instead, the agency sent GPB a written statement defending its management of the forest, which it described as being “in good condition.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service also pointed to proposals it had received from the land trust in years past regarding land acquisition, which the agency described as carrying a “primary risk” in which “the American public will lose equitable access to their public lands and the conservation and public use benefits” of a national wildlife refuge.

The agency wrote that it “remains committed to partnering with the Harris Neck community and continuing the discussion with the [Harris Neck Land] Trust to identify ways to promote the rich history and local cultural heritage, especially as it relates to the ecological importance of Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge and the community's deep connection to wildlife and the land.”

In 2020, the Fish and Wildlife Service signed a memorandum of understanding, not with the Harris Neck Land Trust and its broad coalition of descendant families, but rather with two members of a single family: Frances Timmons and Tyrone Timmons, both descendants of businessman William Timmons, who was the largest Black landowner before the federal government's 1942 takeover.

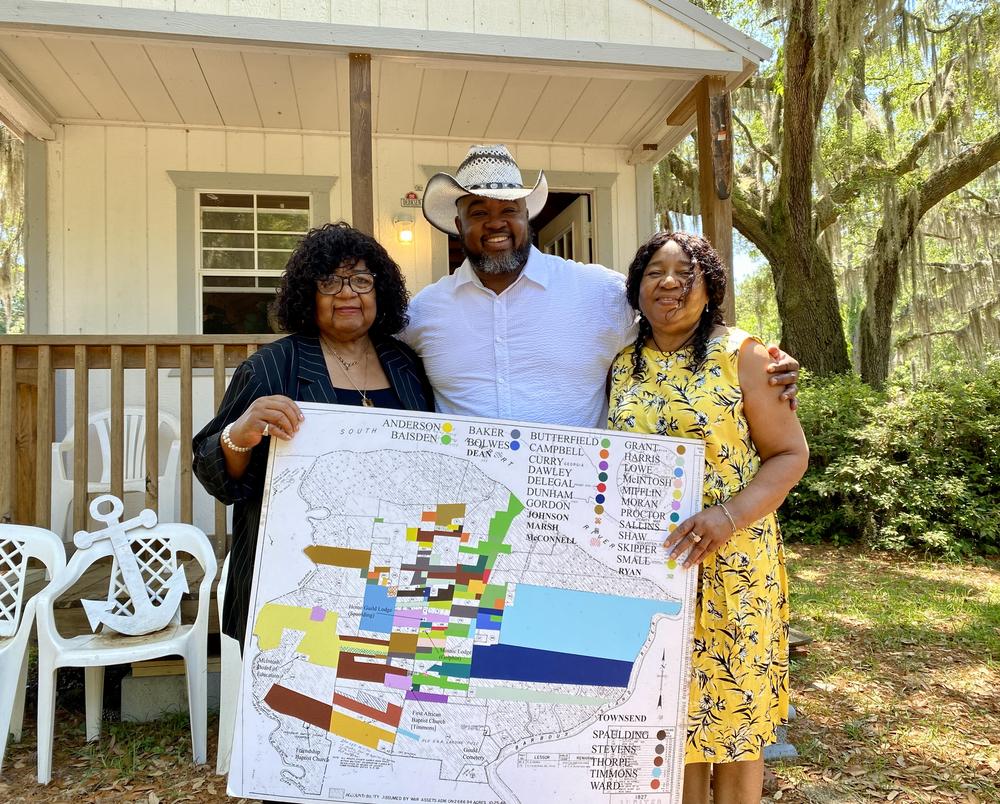

“We have a long way to go, but we have come a long way in a short length of time,” Frances Timmons told GPB in an interview alongside her nephew Tyrone, referring to the group that she founded in 2019 — called Direct Descendants of Harris Neck Community (DDHNC) — after leaving the Harris Neck Land Trust for undisclosed reasons.

“It is extremely important that those 311 acres that we know is ours — it's ours — we should have firsthand knowledge,” continued Timmons, who serves as the group's president. “We should have the first opportunity to make decisions about it, should and when some of it may be returned.”

Direct Descendants of Harris Neck Community founder and president Frances Timmons, vice president Tyrone Timmons and administrative assistant Margaret Timmons Finley pose next to their group's office on Harris Neck Road in McIntosh County, Ga.

The makeup of DDHNC's membership is unclear: when asked for details on who the group represents, Frances Timmons said, “The families that are in our organization. That's who we represent.”

When asked for clarification, she deferred to DDHNC vice president Tyrone Timmons.

“Let me say it this way: all families is what we — we look for all of the direct descendants of Harris Neck,” he said. “We are not opposed to anybody that's a direct descendant of Harris Neck, when it comes to us looking at making decisions or actually working hard. We're not just working hard just for our family, regardless of what anybody might say or anybody might think.”

The memorandum of understanding — which is not legally binding — does not call for transfer of title to any land on Harris Neck; rather, it formalizes what the document describes as “enhanced communication and collaboration” between the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Interior Department and DDHNC.

Tyrone Timmons said that this means “being able to sit down at the table to talk about the different things and work with them on whatever projects they may have going on down there.”

As an example, he pointed to an annual ceremony in July commemorating the government's 1942 takeover — an event which Timmons described as a direct result of the memorandum.

“We have a nice program where we have different speakers and keynote speakers and everything like that,” he said. “And Fish and Wildlife [has been] right there, walking with us hand-in-hand.”

To the Harris Neck Land Trust, land acknowledgments don't go nearly far enough; only land itself can make Harris Neck descendants whole.

“We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors,” Moran said. “And for what happened to them and the trauma they experienced, I can't even imagine.”

He tries to imagine, though. Along the muddy banks of a winding river on the north side of Harris Neck, he points to the horizon.

“Right in that gap right there?” he says, motioning past St. Catherines Island to the east. “That's the Atlantic Ocean. And you know what's over on the other side, right? West Africa. And that's where they took us from and brought us here.”