Section Branding

Header Content

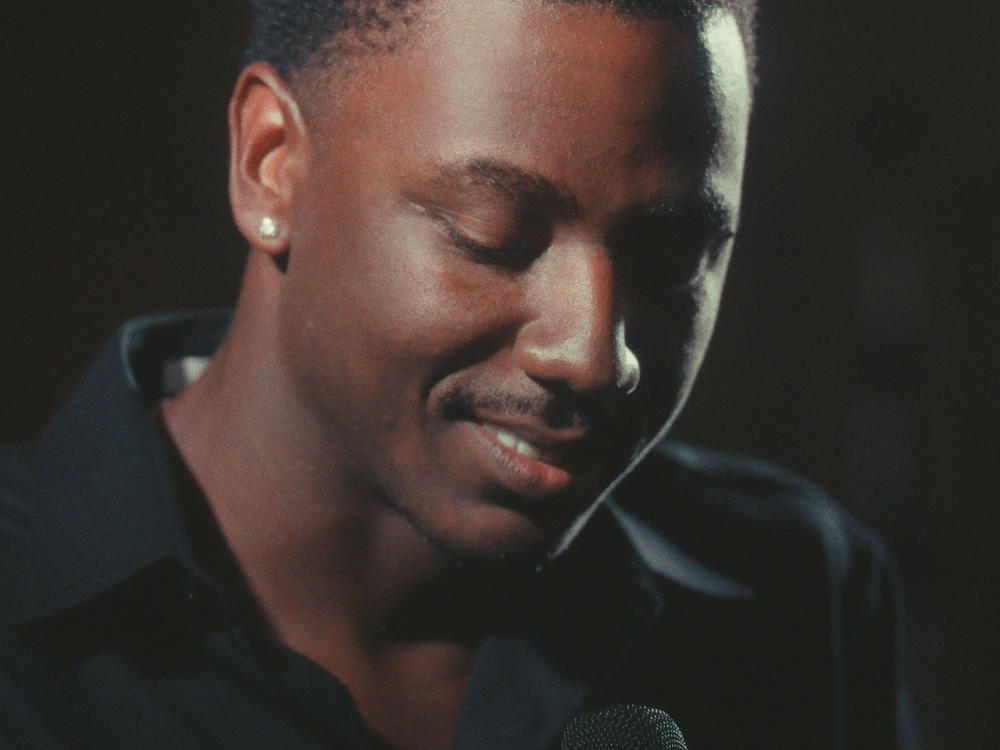

In pursuit of radical honesty, 'Jerrod Carmichael Reality Show' delivers ambiguity

Primary Content

Peruse any online thread discussing Jerrod Carmichael Reality Show, the disquieting HBO series created by and starring the titular comedian and filmmaker, and colorful descriptors like "pretentious," "mega narcissist," and "self-righteous piece of [redacted]" are bound to appear.

"This show seems kinda invasive," one observer noted on Reddit. "... I'm not sure what the obsession is with public humiliation ... About a year ago, I was very much a fan of his honesty and what seemed to be [a] down to earth personality but it looks like it's morphed into the narcissistic cry for help."

Carmichael earned a lot of good will from his 2022 breakout standup special Rothaniel, in which he — among other things — came out publicly as gay and processed his mom Cynthia's devout homophobia. It launched him into the "mainstream"; that is, a stratosphere where one wins prestigious awards, guest hosts Saturday Night Live, and makes headlines for easily agitating the ever-crotchety elder statesman Dave Chappelle.

He was easy to root for because he treated the performance like a therapist's couch, a safe space where he could break through the silence that encourages shame and deceit. It was different from, but in the lineage of, Richard Pryor's recounting of his own drug addiction in Live on the Sunset Strip – confessional, blunt, and refreshingly relatable to those who've shared a similar experience, delivered in the way only a gifted and self-aware comedian can.

But Reality Show practices an entirely different mode of candor. On camera, Carmichael cheats on his boyfriend Mike and later lies about it during their couples therapy session. He misses a friend's wedding because he makes a pit stop to get a hot dog along the way. (He was supposed to be the best man.) He goads his parents Joe and Cynthia into having raw, painful discussions about their once-private lives and tightly held beliefs.

All of this is done in service of what he sees as a greater good: radical honesty, which he in turn hopes will lead to stronger bonds with his loved ones. Yet for some, the show has morphed the perception of him from that of an artist valiantly speaking the truth to an exhaustingly selfish crusader for a very specific truth — his own. And whether or not he succeeds at repairing his fractured relationships is only partially answered by Reality Show's finale, which aired Friday.

Reality Show stands apart

If Rothaniel was presented as catharsis, Reality Show arguably functions as exploitation. It's one thing to process grief, pain, and pathos through your art; it's utterly baffling to directly involve the sources of that pathos in your artistic process, particularly when they seem formidably resistant to even acknowledging themselves as the source.

This isn't the first time. In 2019, Carmichael released two HBO documentary specials that also featured him in conversation with his family, Home Videos and Sermon on the Mount. Home Videos is where he first tested the waters to see how his mom would react to him coming out to her. On camera, he offhandedly dropped in an admission that he's hooked up with men but stopped short at identifying as gay. Cynthia barely acknowledged the unexpected disclosure.

As Carmichael told Dave Holmes for Esquire, the silence from his parents after coming out is what pushed him to create Reality Show in the first place: "The lack of acknowledgment is what made me go, 'Okay, I'll turn the volume up.' How do I make it as extreme as possible? It's testing the limits of their cognitive dissonance."

The extremities make up a strange gumbo: One-part old-school docu-style reality TV (in a different era, this could've been True Life: "My Mom's a Homophobe"); a dash of trashy celeb-reality (think Being Bobby Brown or Britney & Kevin: Chaotic); and another part self-referential prestige experiment (Sarah Polley's Stories We Tell or How To with John Wilson).

For all its cross-cultural parallels, though, Reality Show stands apart. To his credit, while he has near-total creative control as the creator, co-executive producer, and star, he's willing to show himself being challenged by his own cognitive dissonance. Within the first few minutes of Reality Show, he makes his MO plain: "Cameras make me feel more comfortable, I like this — it seems permanent, and it feels really dumb to lie." And yet, we later watch him lie on camera about being monogamous during a couples therapy session with Mike, proving he struggles to adhere to his own ethos, at least at first. (As the season carries on, he and Mike try out non-monogamy together, and seem to find that it works for them.)

The reality TV genre feeds heartily upon the judgmental instincts of its viewers. It needs audiences to engage with it as gossip fodder and opinion-generator, encouraging those who tune in for the "real"-ish drama to scoff at the foolish personalities, cheer on the likable heroes, and boo the flamboyant antagonists. Carmichael clearly understands the format – unscripted in theory, though manipulated and edited to make the "real" fit more neatly into a dramatic arc – and bends it to his will. And while the crudest entries in the reality genre tend to bring up social issues and prejudices either unintentionally or superficially, with Reality Show, Carmichael chooses to purposefully expose the issues in the name of raw, unfiltered honesty.

"I think this will be good for you"

In the mid-2010s, he co-created and starred in the loosely autobiographical network sitcom The Carmichael Show. Far more subversive than its multi-camera, live studio audience format let on, it positioned him as a nihilistic provocateur who revels in frank, multi-generational conversations on an assortment of hot-button issues with his fictional family: abortion, assisted suicide, mass shootings, depression. (It's frequently, and aptly, been referred to as a modern-day All in the Family.)

A Season 2 episode focuses on Jerrod's dad Joe (David Alan Grier) as he prepares to deliver a eulogy for his own father, who was abusive and abandoned the family long ago. Jerrod doesn't understand why Joe would want to honor him – "Am I the only one who remembers what a deadbeat that man was?" – but Joe feels bound by the tradition of never speaking ill of the dead. Jerrod counters that if Joe is going to give the eulogy, he should at least tell the truth about who the man was: "I think it will be good for you."

That line could've been the tagline for Reality Show, which finds Carmichael butting up against the people in his life — many of them older — who bristle at his desire to revisit painful memories from the past. In the fourth episode, Jerrod attempts to have a straightforward conversation with his real dad Joe, and pelts him with a rapid-fire series of questions about the double life Joe led for years, which included having a secret second family with another woman.

"Would you say you loved [the other woman]? Or was it just like, sexual, or was it — 'cause it was a long time, what – like, 40 years of a relationship? Was it hard every time? Did you feel like a bad person?"

Joe, clearly uncomfortable, begins to shut down and insist that the past is the past, but Jerrod keeps pressing him. Joe snaps back: "Why are you digging into this so deep, son?"

I think it will be good for you.

"Is this gonna be on your special?" Joe wearily asks. "This is hard for me to discuss on cameras."

Doing this in front of cameras is the only way Carmichael, a late-30s millennial who came of age in the early years of oversharing – The Real World, blogging, Facebook – knows how to have (or force, really) these conversations. It's telling that, spliced throughout some of the episodes, Reality Show includes footage from the Carmichael family's home videos going back decades, some of which Jerrod himself shot as a kid with a camcorder. The grainy images root the present-day points of conflict firmly in an "authentic" past, suggesting that this project was predestined, something this artist has unintentionally been working toward for decades.

"Your option is no option," Jerrod snaps back at Joe around that campfire, "so don't criticize the way I do it. If the cameras help me, then they f------ help. But your way is nothing, your way is silence, your way is death."

Eventually, Joe is tapped out. "You've expressed yourself ... can I go home?"

The camera gives Jerrod courage, a security blanket to wear while attempting to address the distance between him and Joe, yet it's not yielding the results he's looking for. It's hard not to wonder if the cameras are actually hindering him in the long run, keeping him stuck on the false hope that others around him – who have thus far only proven rigid in their stances – might open up to him the way he wants them to.

Bending his truth for his mom

At the core of Reality Show, nestled beneath the layer of a mission for radical truth, is Carmichael's determination to radically alter worldviews. "Could my mom change?" he ponders at one point. He surmises, "It's reason to keep fighting."

"I'm not going to sit here and lie to you," his uber-Christian mom Cynthia insists in the finale, while repeating yet again that she'd "prefer" that he isn't gay. (In an earlier episode, she likened homosexuality to being a murderer.) Cynthia might be the most authentic of all the figures in Reality Show, unapologetically herself. His impasse with her has less to do with avoiding the truth than it does the fact that her truth stands in direct opposition to his.

She visits Jerrod and Mike in New York City for Mother's Day weekend, and he takes her to a queer-friendly Harlem church, where the pastor pushes back against her insistence that the Bible condemns homosexuality. Later they meet with a queer therapist for joint counseling. Neither of these experiences sees her budging from her stance: "I'd like for him not to be gay," she tells the therapist during one-on-one time, adding matter-of-factly, "I can go further [with my acceptance], I just choose right now not to ... I don't want to."

Later, when she reiterates her desire for him to find a woman to settle down with, he tries meeting her on her terms: He consents to letting her attempt to pray away the gay in front of him. She's truly giddy; it might be the happiest she appears in the entire show. "I love you. That blessed my heart," she says, satisfied. She's completely unaware (or unbothered?) by how her son's body seems to recoil out of deep discomfort.

In an effective bit of dramatic editing, the prayer immediately cuts to Carmichael remarking on the moment during a standup performance. "She was so happy that I let her do it. I immediately regretted it."

Throughout Reality Show, Carmichael imagines standup snippets as if they were a more elevated version of a confessional booth, that reality TV convention where the cast members get to narrate their perspective of the story unfolding. It's devastating watching him concede to her, to allow her this delusion. But there's life as-it-happens and life as reflected upon later. And it's important to note this doesn't come out of nowhere; this has been years in the making, with long periods of absence and occasional heated exchanges, some of which were captured on camera. Through his extravagant attempts at familial reconciliation, Jerrod's ultimately realized he has to bend his truth a little to maintain some sort of relationship with Cynthia.

I think it will be good for you.

"You know what I realized I need is a reason to believe everything will be OK," he adds. "I'm always looking for that. When I was young, I found it in my mother. And now, I'm finding a lot of that in [Mike]." As he says this, a montage of images flurry by: Cynthia packing her bags in her hotel room to go back home to North Carolina; a younger Cynthia smiling for the camera in a home video; Mike teaching Jerrod how to swim in a pool.

A revelatory viewing experience

And yet the finale also suggests a small but perceptible shift in Jerrod's relationship with Cynthia, and proves the show is more than a masochistic, navel-gazey affair (though it's certainly that, too). This is soap opera verité in its most anarchic state — almost certainly a terrible idea for everyone involved, but quite possibly a learning experience for those observing from the outside looking in.

The post-credits sequence is jarringly optimistic. The final image is of Mike and Cynthia laughing together in her kitchen in North Carolina a few months later; she even places her hand affectionately on his back for a quick moment. We have no idea if Cynthia still believes Jerrod and Mike are on equally sinful footing with murderers, though the scene implies something within her has softened.

It's unclear what we're supposed to make of this – that maybe Jerrod's persistence has actually helped him reconnect with his family? If so, it's worth considering Reality Show a success for what he's said he wanted out of this project, even if there's reason to be disappointed in the concessions he may have had to make to get there.

The impulse to question why any of this needed to happen in such a public manner doesn't completely recede with this conclusion, though maybe it makes the show's existence easier to digest. In any case, the ending is hardly pat — real life plays out on its own terms away from the cameras — and Reality Show's frank depiction of a Black queer man attempting to push back against his family's culture of silence moves the needle even further than Rothaniel did. He's provided viewers with an imperfect guide for how to have difficult but necessary conversations with the people they care about (preferably without dropping a camera crew in the mix).

Oddly enough, Reality Show shares a bit in common with the most recent season of the absurdist Netflix dating series Love Is Blind, which featured Clay, a young Black man who also dealt with unresolved trauma stemming from his own dad's infidelities in a very public manner. The show's silly "social experiment" — above all designed for maximum gawking and entertainment — inadvertently stumbled into a candid and relatively honest discussion about Black masculinity and generational trauma.

At Clay's doomed wedding ceremony to AD, his mom Margarita, no longer married to his dad Trevor, gave the series its truest moment thus far, when she explained to Trevor how his actions were affecting their son all these years later. "Your past and things that you witness, it's part of your DNA. It's part of your inside. And if you don't get freakin' help, you bring that s--- into the next thing."

Clay brought his baggage into Love Is Blind and Jerrod brought his into Reality Show. Disarray ensued and feelings were hurt. There's a silver lining though: In making highly questionable decisions for all the world to see, they forced conversations that need to be had but often aren't, and perhaps some viewers may come away feeling inspired to confront similar issues in their own lives. Even amid all the mess, some honesty managed to break through the silence.