Section Branding

Header Content

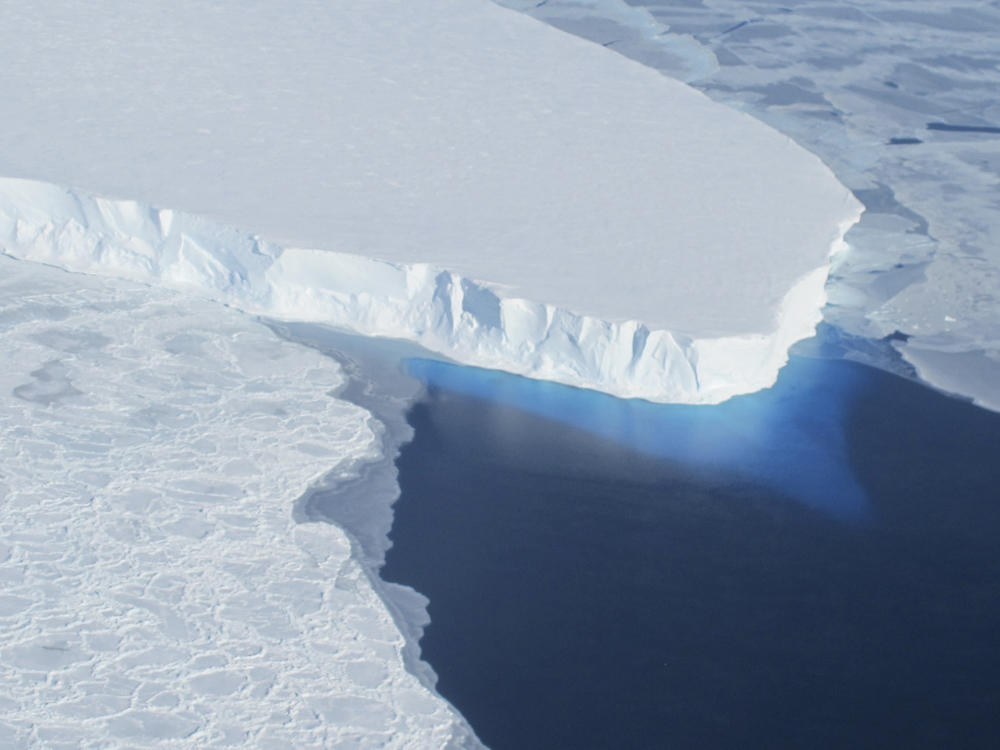

New research on Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier could reshape sea-level rise predictions

Primary Content

A team of scientists say seawater flowing underneath and into gaps in the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica is contributing to the melting of the massive ice formation — a potentially ominous sign of the coming effects of human-driven climate change from the world's widest glacier.

These areas of the glacier may be undergoing "vigorous melting" from warm ocean water caused by climate change, which could lead to even more rapid sea-level rise around the globe.

"The worry is that we are underestimating the speed that the glacier is changing, which would be devastating for coastal communities around the world," Christine Dow, a professor at the University of Waterloo in Canada and co-author of the study, said in a press release.

But researchers say more work is needed to fully understand what effects the warm water is having beneath the ice formation.

At roughly 80 miles across, Thwaites is the widest glacier in the world and roughly the size of Florida. It has been nicknamed the "Doomsday Glacier" for the catastrophic effects its thawing could have on global sea-level rise.

Each year Thwaites loses about 50 billion tons of ice, which comprises roughly 4% of all sea-level rise worldwide, according to the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration. One estimate predicted that the total loss of Thwaites could cause average global sea levels to surge by more than two feet, and could cause sea levels to rise even more in some parts of the U.S.

In the study published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team of glaciologists used radar data taken between March and June of last year by Finland's ICEYE commercial satellite program to get a better idea of what's happening below the surface of the glacier.

They found that seawater flows in and away from the glacier with the tides, mixing with freshwater, but some of that warm ocean water also travels deep beneath the ice formation, going "through natural conduits" or collecting "in cavities" and becoming trapped.

"There are places where the water is almost at the pressure of the overlying ice, so just a little more pressure is needed to push up the ice," said UC Irvine professor of Earth system science Eric Rignot, the study's lead author. "The water is then squeezed enough to jack up a column of more than half a mile of ice."

That salty seawater near the South Pole has a lower freezing point (28 degrees Fahrenheit) than freshwater, which could further contribute to glacial melting.

Dow suggested that additional ice sheet modeling could help scientists better understand what's happening under these major glaciers and develop a more precise timeline of expected sea-level rise across the world.

"This work will help people adapt to changing ocean levels, along with focusing on reducing carbon emissions to prevent the worst-case scenario," Dow said.