Section Branding

Header Content

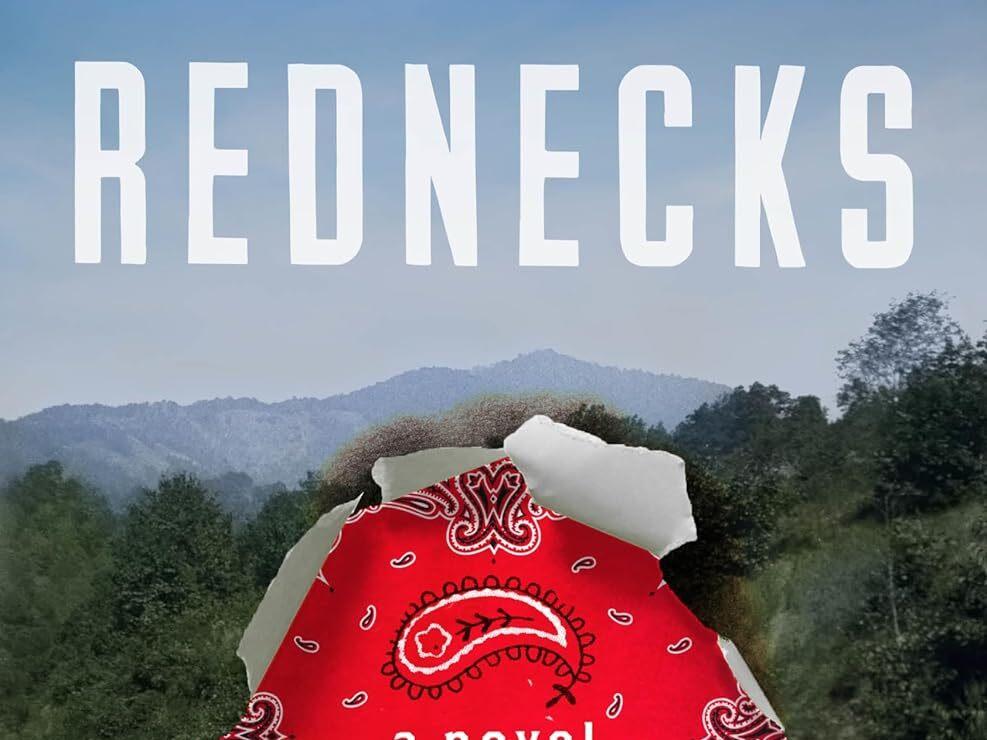

'Rednecks' chronicles the largest labor uprising in American history

Primary Content

Coal, plucked from deep within the earth, helped build this country and got it through many wars. But to get that coal, miners had to put their lives at risk daily and for long, grueling hours.

Between cave-ins, explosions from methane gas, accidents, and black lung, coal mining was a deadly job, and those who benefited from it the most never faced any of those dangers. The result of that division between those putting their lives on the line and those who made the money led to the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921. Around 10,000 miners from all races revolted against the mine owners that fought their union, the government, which sided with the owners, and the state militia.

Taylor Brown's Rednecks is a superb historical drama full of violence and larger-than-life characters that chronicles the events of 1920 and 1921 as it explores the people and reasons behind the largest labor uprising in American history.

Rednecks is a sprawling narrative that kicks off with the Matewan Massacre, which happened in the spring of 1920 when local coal miners and their allies had a bloody shootout with the Baldwin–Felts, who were in charge of evicting people who had joined the miner's union. From there, the novel follows the major events leading up to, and during, the Battle of Blair Mountain.

The chapters follow different characters: "Doc Moo" Muhanna, a Lebanese-American doctor concerned with the health of those stuck in the tent camps and who helped everyone and was respected on both sides of the conflict; Frank Hugham, a Black coal miner and World War I veteran who is beaten and left for dead by the men trying to control the miners and subdue the union; and Beulah, Frank's grandmother, a woman with an unbreakable spirit and a great sense of humor. The novel also has some real-life historical figures in its page: Mother Jones, the fiery, indomitable labor organizer and "Smilin" Sid Hatfield, who played a vital role in the Matewan Massacre and whose mouth full of gold teeth and talent for righteous violence made him a legend.

Rednecks drags readers into the middle of conflict, pulling them into the battlefield, the mines, the streets full of armed men itching to pull the trigger, the courts where good and bad decisions were made, and the cold, muddy tent camps where those displaced by the owner of the mines scraped out a living. Brown, a writer who always delivers impeccable prose, also delivers great pacing and economy of language here, telling a very big story from a variety of perspectives without ever slowing down or getting too caught up in the plethora of details his research surely unearthed.

In fact, there are passages in Rednecks that describe more and accomplish more than some short stories. This paragraph about miners looking at the homes they were kicked out of is a perfect example:

"Now other men slept in those same beds, in the shelter of those hard roofs and milled plank walls. Scabs. Men from out of state, whose labor kept the mines smoking on the hillsides, the coal-carts and conveyors trundling toward daylight. The company ledgers in the black. Kept the Union miners sleeping in canvas tents, their demands unmet. Their wives dull-eyed with hunger, their feet dark-slopped with mud. Their children's faces gaunt, so they could see their little skulls pressing through the skin, creeping toward the surface."

Historical fiction sticks mostly to facts, but that doesn't mean authors can't take a stand and make a point. In Rednecks, Brown makes it very clear from the start: Ihe miners were right. Every time the novel talks about the conflict in depth and explores how it all came to be, Brown reminds readers that the coal miners worked very long hours in awful conditions and mostly wanted things that would help them live longer, things as basic as better ventilation down in the mines. On the other hand, the mine owners were soft men with soft hands who had never set foot inside a mine and who were happy to send entire families to live in cold, muddy encampments or to order murders and beatings just to maximize their earnings. History hasn't been kind to those who stood against the miners unionizing, and neither is Brown.

While this is a novel about something that happened more than 100 years ago, it also feels very timely. Even today, many big companies are very anti-union, and their focus on revenue is the same as it was for mine owners. The division between those who work for a living and those who profit the most from that work is still an issue, and makes this action-packed, character-driven novel feel extremely contemporary.

Gabino Iglesias is an author, book reviewer and professor living in Austin, Texas. Find him on X, formerly Twitter, at @Gabino_Iglesias.