Caption

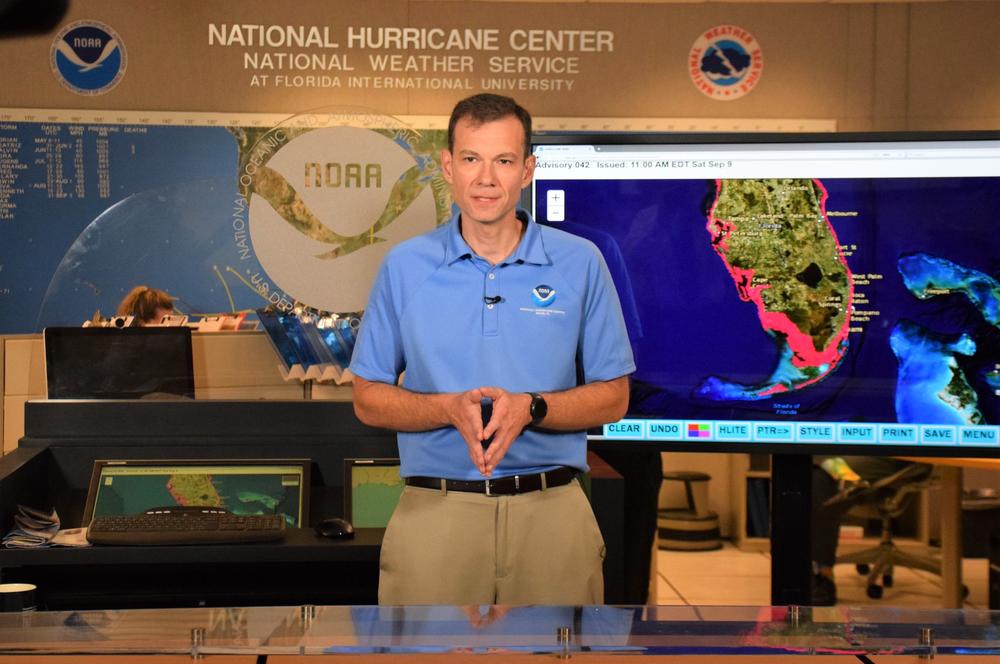

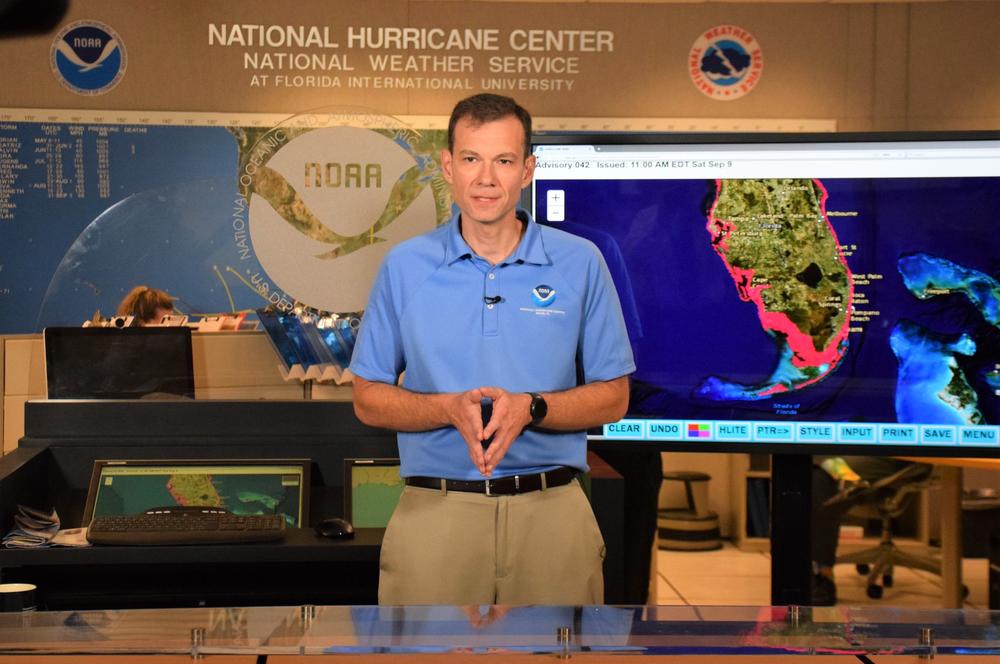

National Hurricane Center deputy director Jamie Rhome at the agency's Miami headquarters in 2019.

Credit: NOAA

LISTEN: National Hurricane Center deputy director Jamie Rhome joins GPB Savannah reporter Benjamin Payne to discuss the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, which officially began June 1 and runs through November.

National Hurricane Center deputy director Jamie Rhome at the agency's Miami headquarters in 2019.

The Atlantic hurricane season is underway, and it's projected to be one for the record books: between now and November, 8-13 hurricanes are likely to develop — the highest range that federal forecasters have ever projected for a hurricane season.

But beyond the sheer number of storms, what else should Georgians be aware of? For that, GPB Savannah reporter Benjamin Payne spoke with Jamie Rhome, who serves as deputy director of the federal government's National Hurricane Center in Miami.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Benjamin Payne: A lot of the discussion around hurricanes revolves around Florida, and understandably so, since hurricanes make landfall more often in that state than any other. But, of course, Georgia is Florida's next-door neighbor. A hurricane can hit Florida first, before barreling north, as we saw last year with Hurricane Idalia hitting the Valdosta area hard. What should Georgians be preparing for this year?

Jamie Rhome: This is a great question, and it speaks to feedback that we're hearing from inland residents that they want to see more focus on the inland aspects of these hurricanes. This has really come to a head more so in the last few seasons, as we've had several storms that retain their strength and wind speed and cause a tremendous amount of destruction well inland.

So, my message to these inland communities is that hurricanes can carry strong wind inland. Often they're weakening as they're traversing these inland communities, which can give people a false sense of security that, “Oh, it's weakening. It's not as strong as it was.”

But there are unique aspects of inland communities that make them particularly more vulnerable sometimes to the inland wind. Like, I grew up in North Carolina, where the soil is clay. And what happens is that the tree roots don't grow down. They grow out laterally. That makes them easier to topple. You get power outages, blocked roads and sometimes the trees fall on homes. So, it's really important to take these inland systems seriously even though they're weakening, because they can really do a tremendous amount of damage.

Benjamin Payne: In Savannah, where I am, people often talk about the threat of a hurricane as coming through either the “front door” or through the “back door,” as I've heard it put — the front door being the Atlantic Ocean and the back door being inland areas, where a hurricane comes up north from the Gulf Coast and into Southwest Georgia. Are there any important differences between Atlantic hurricanes and Gulf Coast hurricanes, aside from the obvious fact of where they make initial landfall?

Jamie Rhome: Well, I certainly understand that way of trying to categorize storms. It's natural for humans to want to categorize things, to make them more simple to understand. But hurricanes are kind of like people. Imagine if you took all personalities and you tried to put it in one or two types, right? You would lose some information and overgeneralize personalities.

The same can be said with hurricanes. If you try to put them in "back door" or "front door," you're going to lose a lot of critical information. Instead, we need people to focus on the specifics of that storm. It's possible that in one case, a back-door scenario can produce more impacts than a front-door scenario, or vice versa. ... So, I really want people to think more deeply about storms and avoid that sort of oversimplification.

Benjamin Payne: A big reason this year's hurricane season is forecast to be above normal is because La Niña is likely to form. Can you explain what this climate pattern exactly is, and why it's more conducive to hurricanes than El Niño?

Jamie Rhome: El Niño and La Niña — collectively called ENSO — is the warming or cooling of the ocean in the Pacific. What does that have to do with us in the Atlantic? It changes the global atmospheric conditions: In one phase, it produces atmospheric conditions that are not conducive for hurricanes, with El Niño. And the opposite — La Niña — produces atmospheric conditions that enable hurricanes to form and become stronger. So we're trending towards the latter.

But there are other factors at play. El Niño and La Niña tend to dominate the discussion, but there's probably five to eight other factors happening that control hurricane activity, and they don't tend to get discussed as much. The other thing, too, is when you're trending from one to the other — we're trending towards La Niña — it's not like when you flip a switch and the lights come on. The reaction, or the forcing that happens from La Niña that helps hurricanes form is not instant. So, it really depends on how quickly La Niña develops. And then there's a little bit of a lag in the response, too.

So, there's still a lot we don't know about the season and how it's going to play out. And so that uncertainty means that, as a citizen, you really have to just be prepared, and not get too bogged down in the hype, and just really focus on yourself and making your family ready.

Benjamin Payne: Can you explain what wind shear is and what it has to do with hurricanes? It's one of those factors that I see hurricane watchers bring up from time to time.

Jamie Rhome: Wind shear is basically like the winds in the jet stream. If you fly on a commercial flight, sometimes the headwinds slow you down and sometimes the tailwinds speed you up, and you get to your location sooner or later than you hope. And sometimes those winds cause turbulence and cause the flight to be rougher than normal.

That's basically what wind shear is: how much the winds get stronger as you climb up in the atmosphere. Hurricanes don't like that at all. They like the winds to be consistent from top to bottom, meaning that they don't like any sort of change in the winds above them than at their feet. If we go into a La Niña, what tends to happen is the wind shear decreases, goes down, and that's what supports storms forming.

Benjamin Payne: Any final advice for those of us here in Georgia?

Jamie Rhome: ... Do what I'm doing: I spent last weekend in my garage, testing and tuning up my generators, making sure that they're ready and everything's situated, making sure the supplies were kind of where I thought they were. My garage is kind of like everybody else's garage: It becomes sort of the dumping ground for all these miscellaneous things. So, I made sure my supplies were where I thought they were, dusted off a few things and added a few things. Nothing really big, because I prepare every season.

Just do the small stuff to make sure you're ready, because when you do it in advance of [right before] a storm, everybody else is trying to do the exact same things. The roads are crowded, there are long lines, you can't get what you need, supplies are out and you can't get fuel because everybody's trying — all the procrastinators are trying to do it at the exact same time. You'll make your life so much less stressful if you just go through the motions now and do the small things to prepare.