Section Branding

Header Content

Data dive: What is ‘affordable housing’ in Coastal Georgia? It depends

Primary Content

Maggie Lee, The Current

What’s “affordable” housing depends on what’s in your wallet. But zoom out to all of coastal Georgia, cross-reference a federal guideline and it shows most four-person families can “afford” housing ranging from zero up to about $2,300 per month.

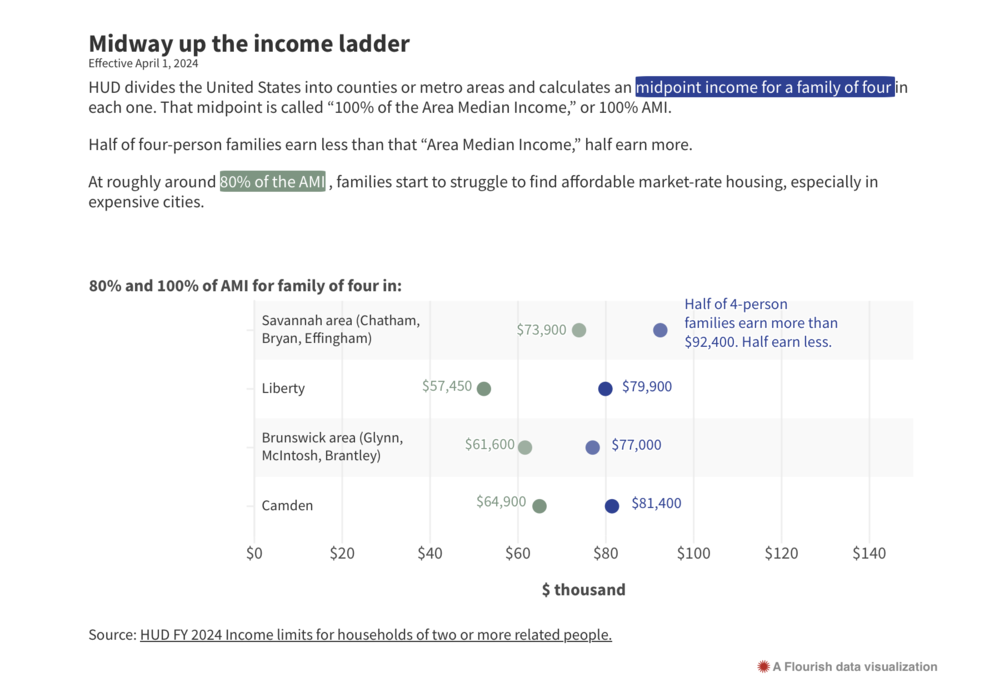

For a family of four, the midpoint on the coastal income ladder is somewhere from $77,000 to $92,400, depending where they live, according to newly published numbers from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. According to the spending guidelines from the same department, families should aim to spend no more than 30% of that income on housing.

This local HUD income number is — or should be — important for local policymakers when they’re trying to decide what kind of housing and public services will be built in their communities. Can their constituents afford large apartments, or small townhouses or single-family homes 10 miles from anything? Should zoning allow carriage houses? Duplexes?

Some cities use the HUD income numbers to set local policy, like subsidies for developers who will set below-market-rate rents that, say, a teacher or firefighter can afford on 30% of their income.

Housing authorities use HUD income numbers to know who can get in line for a housing voucher.

Activists use HUD income numbers and the 30% rule when they’re urging policymakers to subsidize or prioritize the construction of yet more attainable housing.

So it’s an important benchmark number for people who want to understand and start to fix housing shortfalls in their communities.

When families can’t find housing, the story is familiar: Strained budgets and long commutes are the start of the problems. At worst, it’s actual danger like slumlords and homelessness.

The number tells you all at once what your co-workers, the other parents at school, the cooks and the delivery folks and lawyers all see when they look in their wallets too.

So here are incomes in your community and what HUD says people can afford.

What’s in your neighbor’s wallet

A family of four that makes $92,400 per year is in the center of the income ladder for a household of that size in the Savannah area, defined by HUD as Bryan, Chatham and Effingham counties, for the year starting April 1, 2024.

Half the four-person households in that Savannah area make more than $92,400 and half make less than that — so that’s the “area median income” income for a four-person household.

That four-person household could be one parent with an income and three children. It could be a couple who each have an income and their two children. It could be a grandparent with some retirement income, a working parent and two children. It could be any combination of four related people.

If a family is bigger, its median income is higher, and in a smaller family it’s lower, and HUD calculates all of that.

But the benchmark starting point is that family of four.

Above the median income, housing can be more about choice, preferences, location, and convenience. A lot further up the ladder, there’s even luxury and character.

But below the median income, the pressure starts.

What that income buys

“I would say that the challenge in Savannah is that a lot of our service industry folks and our entry-level professionals are no longer able to afford rent or a mortgage within Chatham County,” said Laura Lane McKinnon, executive director of Housing Savannah, a nonprofit that advocates for affordable housing. “Folks are increasingly having to move further and further away from either their schooling or their employment.”

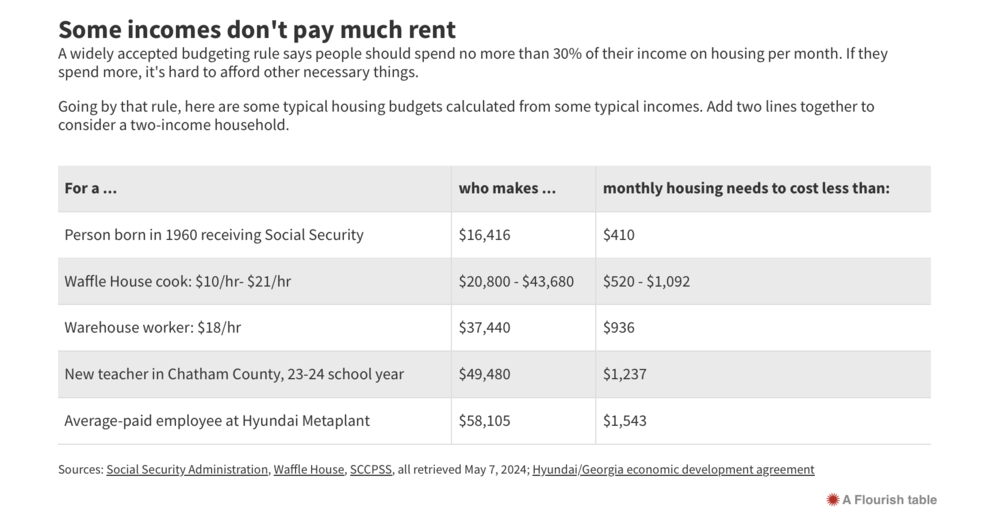

The 30% rule about housing spending comes from what HUD expects some low-income clients to pay toward subsidized housing. Households need at least 70% of their income to pay for cars and gas, groceries, health care, savings, child care, deposits, down payments and other parts of life.

In high-cost cities, folks may need even more than 70% for the other stuff. Or when a family’s income is low in the first place, 70% may not cover all the other things.

Look at it this way: a family that makes $100,000 would have about $70,000 left after spending 30% on housing. $70,000 will buy a good bit of child care and transportation and savings.

But a family at $50,000 would have only $35,000 left over after spending 30% on housing — and that’s starting to slip into the place where the housing burden is too heavy and other parts of life are left underfunded or unfunded.

Of course, lots of families do stretch their money and spend more than 30% of their incomes on housing, but that comes with risks: nothing for emergencies, expensive title pawns, leaning too hard on family for child care, driving a car that needs new brake pads.

Home shopping

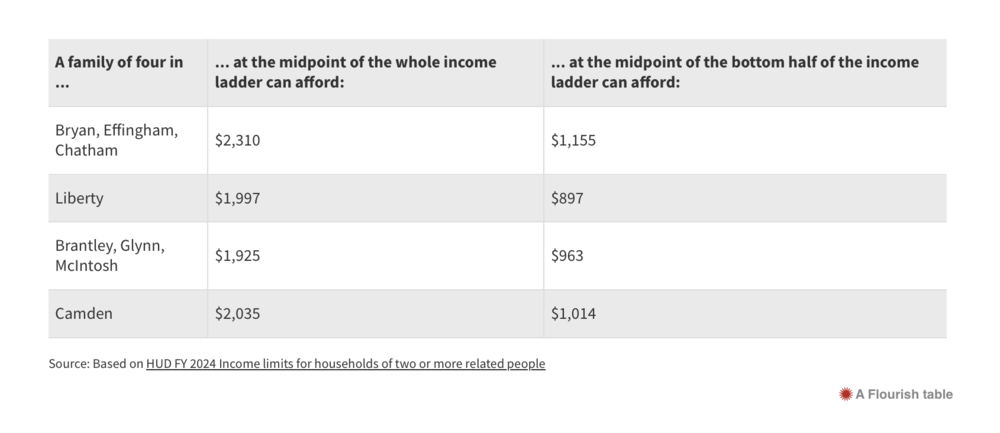

So, let’s go back to that benchmark family of four who are halfway up the income ladder and need some place to live.

And let’s also look at another family whose income is at the midpoint of the bottom half of the income ladder. That family is at “50% of the Area Median Income.”

Three-quarters of four-person families make more than them. One quarter make less than them.

Families there struggle to find housing, though in a way it’s hard to put a number onto it.

A scroll through Zillow or other real estate sites is a glance at real-time market prices, but can miss important parts of the market like mom-and-pop landlords who don’t advertise online. And advertised prices don’t include utilities.

As for buying, Savannah Area Realtors, looking at Chatham, Effingham and Bryan counties, calculated that the median home sale price in March was $344,000. A typical mortgage payment on such a house — without utilities — is just about what that median family of four can afford. Just attainable on paper, supposing the family has been able to save a down payment or maybe tap the “bank of mom and dad.”

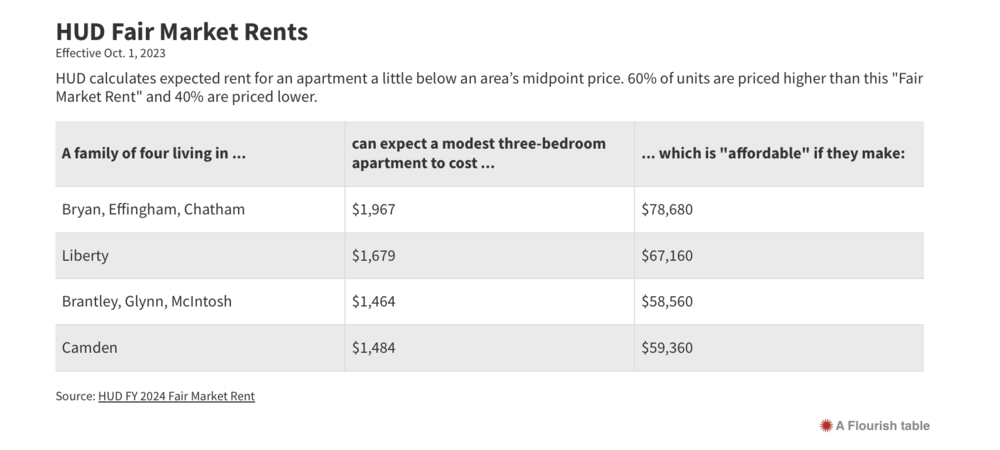

HUD takes its own look into housing costs from a different way, publishing “Fair Market Rent” numbers, which start with a U.S. Census survey of what people are actually paying. That’s a little closer to the full reality, but the math takes a while; they’re not real-time numbers.

But for every area, HUD publishes the cost, with utilities, of an efficiency and a one-, two-, three- or four-bedroom apartment that’s a little below the midpoint price in an area. In jargon, HUD is publishing “40th percentile” costs.

But all these price points assume that people can even find an available apartment or home. Fear of displacement is real when the owner of a mobile home park or apartment building decides to sell out.

The fear of making noise is real, too. Hinesville City Council member Diana Reid said she has constituents who are scared to complain to landlords about rats or broken appliances because they’re afraid of losing a place they can afford — and maybe with an eviction on their record, which would make moving even harder.

“They want a decent place to live, we’re sick of slumlords,” Reid said. “But they get away with it because they know people are pressed for a place to live.” She said there are landlords who collect the rent money but don’t want to fix anything.

Hineseville lets in businesses like Kroger and Walmart and fast food places, Reid said, but that those jobs don’t pay enough for employees to afford the housing that the city is letting in at the same time.

“So this is what you make per hour, but then we’ll allow people to build this [housing]? It doesn’t make any sense, right?”

In Chatham County, homebuilders can’t build a single-family home for less than $300,000, said McKinnon of Housing Savannah.

“They are struggling to build anything that is valued at less than that and what we need with the prevailing wage for our area is we need homes that are between $150,000 and $250,000.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Current.